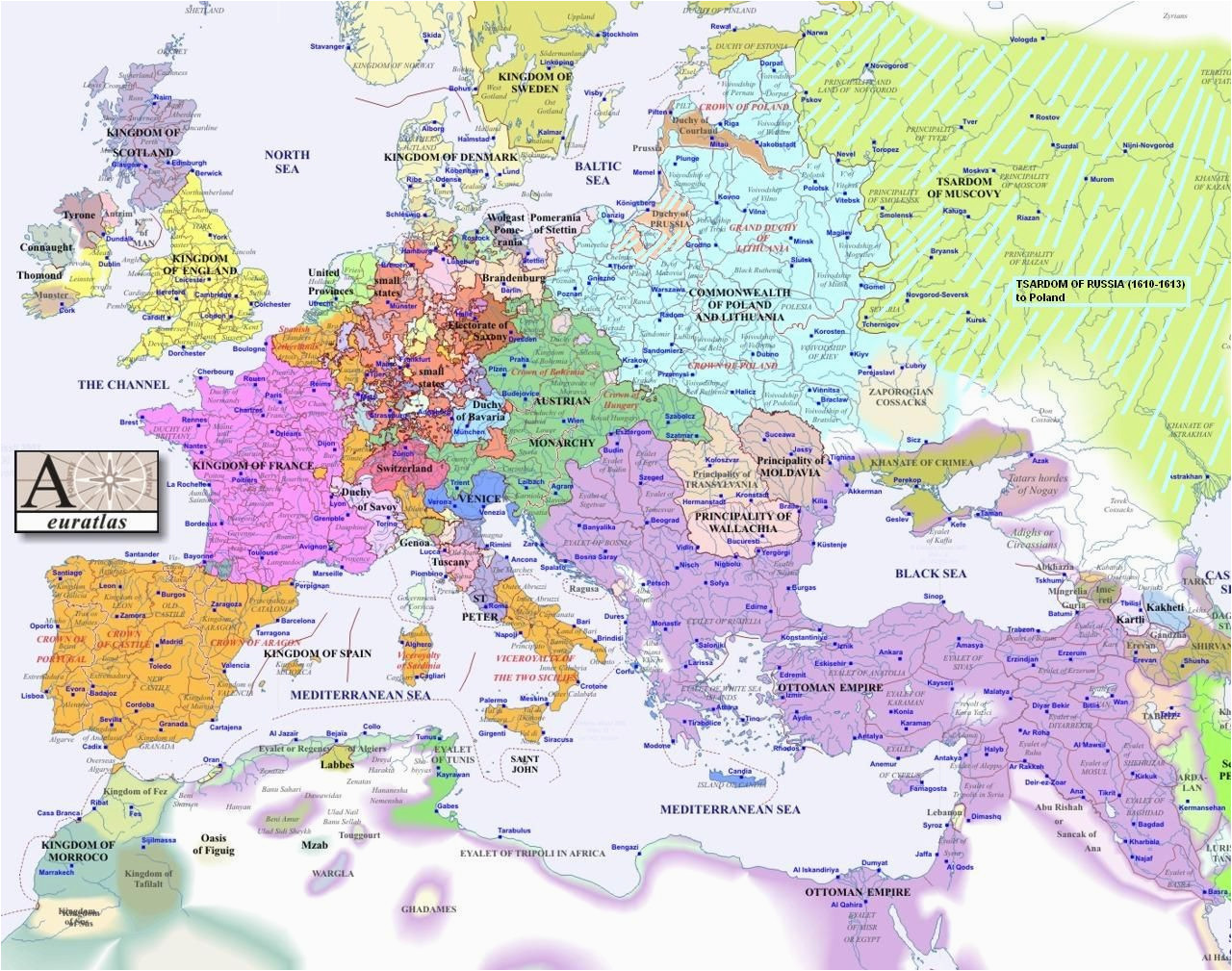

If you look at a map of Europe in the 17th century, it honestly feels like looking at a shattered stained-glass window. It’s messy. It’s chaotic. Borders didn't really work the way they do now, and honestly, the "countries" we think we know weren't even countries yet. They were a jumble of dynastic holdings, bishoprics, and weird little enclaves that make modern geography look like child's play.

You’ve got the Holy Roman Empire sitting right in the middle, looking like someone dropped a plate of spaghetti on the floor. It wasn't one thing. It was hundreds of tiny entities. Then you have the Ottoman Empire creeping up from the southeast, and a version of France that was desperately trying to stop being a collection of feudal lords and start being a real state. People get this wrong all the time because they project 21st-century logic onto 1600s chaos.

Cartography back then wasn't just about "where is the mountain?" It was a political weapon. If a king paid a mapmaker, that map was going to show his land as bigger and his rivals as smaller. It was basically the Instagram filter of the 1600s.

The Holy Roman Empire: A Cartographer's Nightmare

Seriously, look at the center of any map of Europe in the 17th century. You’ll see this massive, blobbish area labeled the Holy Roman Empire. Voltaire famously joked it wasn't holy, Roman, or an empire. He was right. It was a patchwork. There were Free Imperial Cities, ecclesiastical states ruled by bishops, and tiny duchies that you could walk across in half a day.

The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) changed everything here.

Before the Peace of Westphalia, borders were fluid. After 1648, we start seeing the birth of "sovereignty." This is a huge deal. It’s the idea that a ruler has total control over their bit of dirt, and nobody else gets to poke their nose in. But even then, the map stayed messy. You had places like the Spanish Netherlands (basically Belgium today) which were owned by Spain but nowhere near Spain. Imagine if Texas was owned by France today, and you’ll get a sense of how weird the 17th-century logistics were.

Maps from this era, like those produced by the Blaeu family in Amsterdam, are gorgeous works of art. The Atlas Maior was the most expensive book of the century. It wasn't just for navigation; it was a status symbol for the ultra-wealthy. If you owned a high-quality map, you were basically saying you owned the world, or at least understood it.

When "Germany" and "Italy" Didn't Exist

It’s kinda wild to think about, but there was no "Germany" or "Italy" on a map of Europe in the 17th century.

🔗 Read more: Deg f to deg c: Why We’re Still Doing Mental Math in 2026

Italy was a collection of Spanish-controlled territories in the south, the Papal States in the middle, and various republics like Venice and Genoa. Venice was still a powerhouse, though its grip was slipping as trade moved to the Atlantic. People living in Florence didn't think of themselves as "Italian." They were Florentines. The map reflected this fragmentation.

In the north, the Swedish Empire was actually a superpower. We don't think of Sweden as a conquering juggernaut today, but in the 1600s, they owned chunks of Germany, Estonia, and Latvia. They turned the Baltic Sea into a "Swedish Lake." If you look at a map from 1658, Sweden looks terrifyingly large.

- The Dutch Golden Age: Tiny Netherlands was punching way above its weight. They were the world's bankers and mapmakers.

- The Rise of Prussia: Watch the northeast corner of the Holy Roman Empire. A small electorate called Brandenburg starts eating its neighbors. This is the seed of modern Germany.

- The Ottoman Presence: Most people forget that the Ottomans controlled almost the entire Balkan Peninsula. They were at the gates of Vienna as late as 1683.

The Weirdness of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

One of the biggest shapes on the map of Europe in the 17th century is a country most people couldn't point to today: The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. At its peak, it was massive. It covered parts of modern Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, and even bits of Russia.

It was a strange, elective monarchy where the nobles had more power than the king. This eventually led to its downfall, but in the mid-1600s, it was a giant. When you see it on a map, it reminds you that European history isn't just "England vs. France." The East was just as powerful, if not more so, for a long time.

Then you have Russia. Or "Muscovy," as it was often called earlier in the century. Peter the Great hadn't quite dragged it into the "Western" world yet. On most maps from the early 1600s, Russia is just a big, snowy mystery on the edge of the paper, often decorated with illustrations of bears or "Tartars" because the cartographers didn't actually know what was there.

Why 1648 is the Most Important Date on the Map

The Peace of Westphalia didn't just end a war; it redrew the soul of Europe.

If you compare a map from 1610 to one from 1660, the changes are subtle but deep. Switzerland and the United Provinces (Netherlands) were finally recognized as independent. This was a "mic drop" moment for the Habsburgs, who had been trying to keep everyone under their thumb for centuries.

💡 You might also like: Defining Chic: Why It Is Not Just About the Clothes You Wear

The Habsburgs were the Kardashians of the 17th century—they were everywhere. They ruled Spain, parts of Italy, Austria, Hungary, and Bohemia. Their "empire" wasn't a solid block. It was a scattered collection of land they’d won through marriage or war. This is why 17th-century maps have so many "exclaves." A king might own a town three hundred miles away from his capital just because his grandmother inherited it.

The concept of a "natural border"—like a river or a mountain range—started to gain traction toward the end of the century, especially under Louis XIV of France. He wanted the Rhine to be his border. He spent decades (and a lot of lives) trying to make the map look "tidier" for France.

Cartography was the 17th Century's Silicon Valley

In the 1600s, Amsterdam was the center of the mapmaking universe.

The Dutch were the best at it because they had the best ships and the best spies. Mapmaking was high-tech. It required advanced math, engraving skills, and a global intelligence network. Willem Blaeu and his son Joan were the titans. Their maps weren't just functional; they were covered in sea monsters, elaborate compass roses, and tiny drawings of indigenous peoples in the margins.

But here’s the thing: they were often wrong.

You’ll find 17th-century maps where California is an island or where the coastline of Norway looks like a jagged mess of teeth. Even in Europe, the inland geography was often based on "I heard from a guy who went there once." It wasn't until the late 1600s, when the French Académie des Sciences started using triangulation and more accurate telescopes, that the map started to resemble what we see on Google Maps today.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Map Collectors

If you're looking at a map of Europe in the 17th century for research or as a hobby, you need to be careful. You can't just take the lines at face value. Here is how to actually read one of these things without getting misled.

📖 Related: Deep Wave Short Hair Styles: Why Your Texture Might Be Failing You

1. Check the Publisher's Bias

If the map was printed in Paris, the French borders will look "right" and the Spanish lands will look like they’re encroaching. Always look at the cartouche (the decorative frame around the title) to see who commissioned it.

2. Look for the "Ecclesiastical" States

Don't be confused by the dozens of tiny states in Germany. Many were ruled by Bishops. They had no "nationality" in the modern sense. If you see a name like "Archbishopric of Mainz," that's a political entity, not just a church district.

3. Watch the Coastlines

The 17th century was a time of massive land reclamation, especially in the Netherlands. The coastline you see on a 1640 map might be miles away from where it is now. These maps are a snapshot of a world that was literally being built.

4. Follow the Dynasties, Not the Languages

Language didn't define borders. A French-speaking town could easily be part of the Spanish Empire. When studying the map, trace the family names—Habsburg, Bourbon, Vasa, Stuart. That’s where the real power lines were drawn.

5. Get a High-Resolution Digital Scan

Don't bother with cheap reprints if you're trying to see the details. The Library of Congress and the British Library have digitized thousands of 17th-century maps. You can zoom in to see individual windmills or fortified towns.

The 17th century was the bridge between the medieval "idea" of the world and the modern "reality" of it. The maps reflect that awkward transition. They are beautiful, confusing, and slightly inaccurate—just like the century itself. To understand the map is to understand the struggle of a continent trying to figure out what a "nation" actually was.