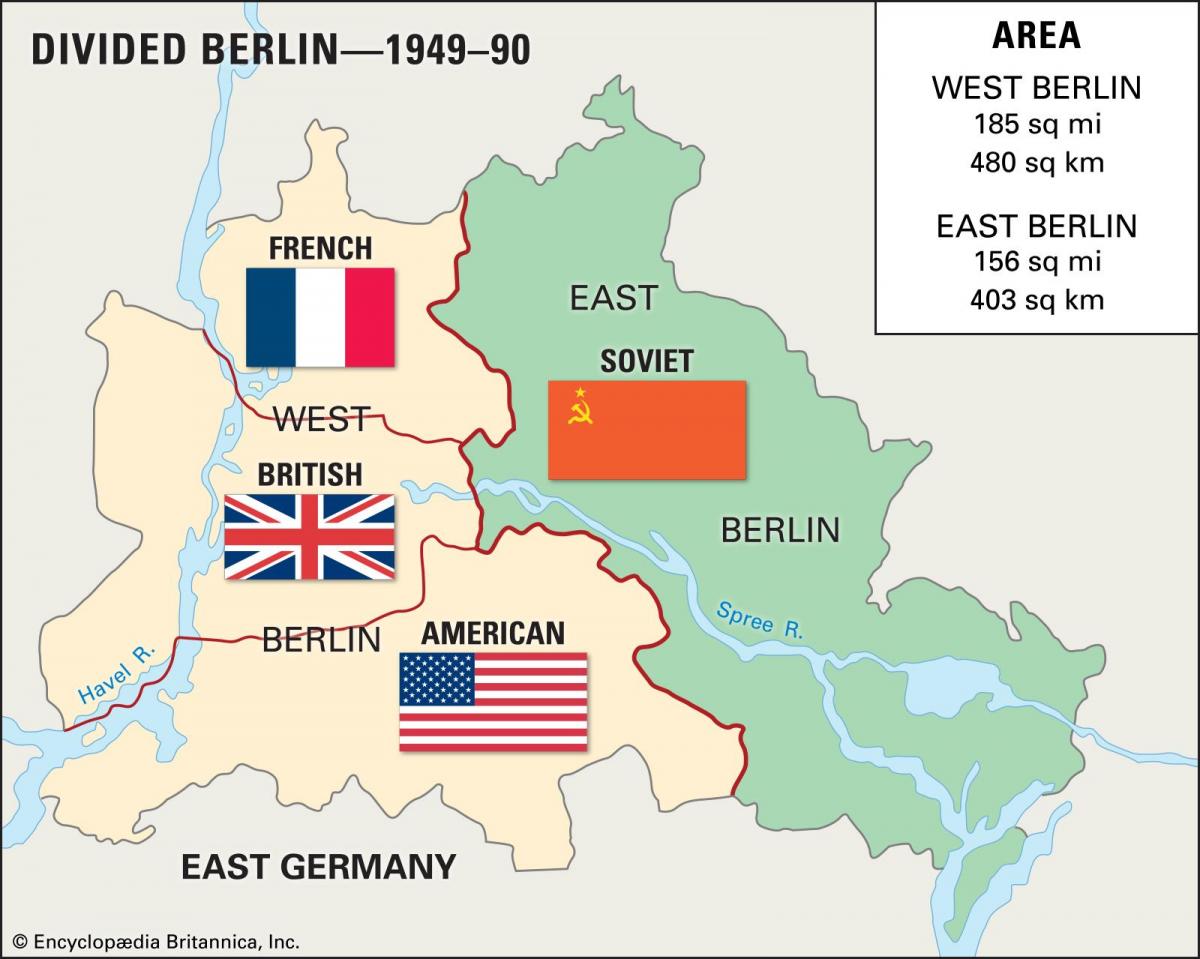

Look at a modern map of Berlin today and you see a sprawling, unified metropolis. It's seamless. But for nearly thirty years, the map of East West Berlin was a cartographic nightmare that defied logic, geography, and often, basic human rights. It wasn't just a line in the sand. It was a jagged, concrete scar that didn't even follow a straight path.

Most people picture a simple vertical line cutting the city in half like an apple. That's wrong. The border was a 155-kilometer (96-mile) loop that physically wrapped around West Berlin, turning it into a democratic island floating in a sea of East German territory. It was weird. It was claustrophobic. And honestly, the more you look at the old layouts, the more you realize how insane the daily logistics actually were.

The Ghost Stations and the Underground Maze

One of the eeriest parts of the map of East West Berlin wasn't even above ground. It was the "Geisterbahnhöfe" or Ghost Stations.

Imagine you’re sitting on a West Berlin U-Bahn train. You’re traveling from one part of the West to another, but the tracks happen to cut underneath East Berlin territory. Suddenly, the train slows down. You peer out the window into the darkness of a station like Nordbahnhof or Potsdamer Platz. The lights are dimmed. Dust covers everything. Armed East German border guards stand in the shadows, watching the train pass but never letting anyone off.

These stations were frozen in time from 1961 until 1989. The GDR (East Germany) walled them off, bricked up the entrances from the street, and literally erased them from their own official maps. If you were a citizen in the East, those stations simply didn't exist. They were blank spots on the paper.

Yet, the West Berliners still used the lines. They paid the GDR a yearly fee in hard currency—millions of D-Marks—just for the right to run trains through the tunnels. It was a bizarre capitalistic arrangement between mortal enemies. The maps used by Westerners showed these stations with a little "P" for passing through, while Eastern maps showed a void. It’s a perfect example of how the city’s geography was a weapon of psychological warfare.

📖 Related: Doylestown things to do that aren't just the Mercer Museum

The Enclaves: Steinstücken and the Map’s Tiny Glitches

If you think the main border was complicated, you haven't seen the enclaves. This is where the map of East West Berlin gets truly "Inception" levels of confusing.

Take Steinstücken. It was a tiny patch of West Berlin territory that sat entirely inside East Germany, physically detached from the rest of the city. For years, the only way for the 200 or so residents to get to work or school was to pass through an East German checkpoint, drive down a narrow road, and then enter West Berlin.

It was a logistical disaster.

Eventually, in 1971, a land swap happened. The Soviets and the Allies agreed to trade tiny slivers of land to create a narrow corridor—basically a paved driveway—connecting Steinstücken to the West. This corridor was fenced on both sides with high walls. You’d be driving to your house, technically in the West, but looking through chain-link fences at East German farmers just a few feet away.

- Lenné Triangle: Another weird spot. A tiny piece of land near Potsdamer Platz that belonged to the East but was outside the Wall. It became a lawless squatters' camp because West Berlin police had no jurisdiction to enter, and East Berlin guards couldn't be bothered to cross the Wall to clear it.

- The Land Swaps: Over the decades, the "official" map changed dozens of times as the two sides traded bits of forest or empty lots to simplify the border.

- Bernauer Straße: The most famous street where the sidewalk was West and the apartment buildings were East. People literally jumped out of their windows to defect until the GDR bricked the windows shut.

How the Map of East West Berlin Defined the "Death Strip"

You can't talk about the map without talking about the "No Man's Land." On paper, the border is a line. In reality, it was a massive, empty void called the Todesstreifen (Death Strip).

👉 See also: Deer Ridge Resort TN: Why Gatlinburg’s Best View Is Actually in Bent Creek

In some parts of the city, like near the Brandenburg Gate, the Wall wasn't just one wall. It was two. Between them lay a wasteland of raked sand (to show footprints), signal wires, trip-flares, and "Stalin’s Grass"—steel spikes hidden in the dirt.

The East German government spent an astronomical amount of money maintaining this void. According to records from the Stasi (the East German secret police), the cost of the border fortifications was a major factor in the country's eventual economic collapse. They were literally spending themselves into bankruptcy to maintain a line on a map that their own citizens weren't allowed to see.

Mapping the Discrepancies: East vs. West Perspectives

The maps themselves told different stories. If you bought a map in West Berlin in 1980, it showed the whole city. East Berlin was there, but it was marked as "Soviet Sector."

But if you bought a map in East Berlin? West Berlin was often a literal "terra incognita." It was frequently depicted as a gray, featureless blob or a blank white space labeled "Westberlin." The GDR wanted to promote the idea that West Berlin was an anomaly, a cyst in the middle of their socialist utopia. They didn't want their citizens to see the street names or the parks in the West because that might make it feel real. It might make them want to go there.

Even the transit maps were propaganda. The East Berlin S-Bahn maps would show the lines stopping abruptly at the border, as if the world simply ended at Friedrichstraße.

✨ Don't miss: Clima en Las Vegas: Lo que nadie te dice sobre sobrevivir al desierto

Why This History Matters for Travelers Today

Walking the line of the map of East West Berlin today is an exercise in spotting "the invisible." You can still see it if you know where to look.

- The Double Row of Cobblestones: In many parts of the city, there is a line of bricks set into the asphalt. This marks exactly where the Wall stood. It winds through playgrounds, across busy intersections, and through the middle of plazas.

- The Street Lights: This is one of my favorite "hidden" map features. In the East, the street lights often use sodium vapor bulbs that give off a warm, orange glow. In the West, they transitioned to fluorescent or LED lights with a cooler, whiter tone. If you look at Berlin from the International Space Station at night, you can still see the border. It’s a map made of light.

- The Architecture: Look at the "Plattenbau" (pre-fab concrete apartment blocks). They dominate the skyline of the former East. Meanwhile, the West has a more eclectic mix of post-war modernism and restored 19th-century Altbau.

Navigating the Legacy

Berlin is one of the few places on Earth where you can physically walk through a historical anomaly. To really understand the map of East West Berlin, you have to stop looking at it as a static image and start seeing it as a living, breathing record of a city that was torn apart and stitched back together.

If you’re visiting, don’t just stick to Checkpoint Charlie. It’s a tourist trap. Instead, head to the Berlin Wall Memorial on Bernauer Straße. That’s where the map becomes real. You can stand on a viewing platform and look down into a preserved section of the Death Strip. You see the watchtower. You see the inner wall. You see how the geography was designed to dehumanize.

Practical Steps for Your Own "Map" Exploration:

- Download the "Berliner Mauer" App: It uses GPS to show you exactly where the Wall was in relation to your current position. It’s the best way to visualize the old map while standing in the modern city.

- Ride the M10 Tram: Often called the "Wall Line," it follows large sections of the former border.

- Visit the Tränenpalast (Palace of Tears): This was the departure hall for people traveling from East to West at Friedrichstraße station. It’s a chilling look at how the border felt to the people who had to cross it.

- Check out the Mauerpark: On Sundays, it's a giant flea market and karaoke hub, but it used to be a desolate stretch of the Death Strip. The transformation is the ultimate proof that maps can change, and cities can heal.

The map of a divided Berlin wasn't just about politics; it was about the fundamental human desire to connect despite the barriers. Today, that map is a reminder that no wall is ever truly permanent.