Look at a satellite image of Germany at night. Seriously, go pull up Google Earth and look at Berlin. You’ll see it immediately. The streetlights in the East glow with a warm, yellowish sulfur hue, while the West shines in a colder, whiter fluorescent light. It’s been decades since the Wall fell, but the map of East and West Germany isn’t just some dusty relic in a history textbook. It’s a living, breathing ghost that dictates where people live, how much they earn, and even how they vote.

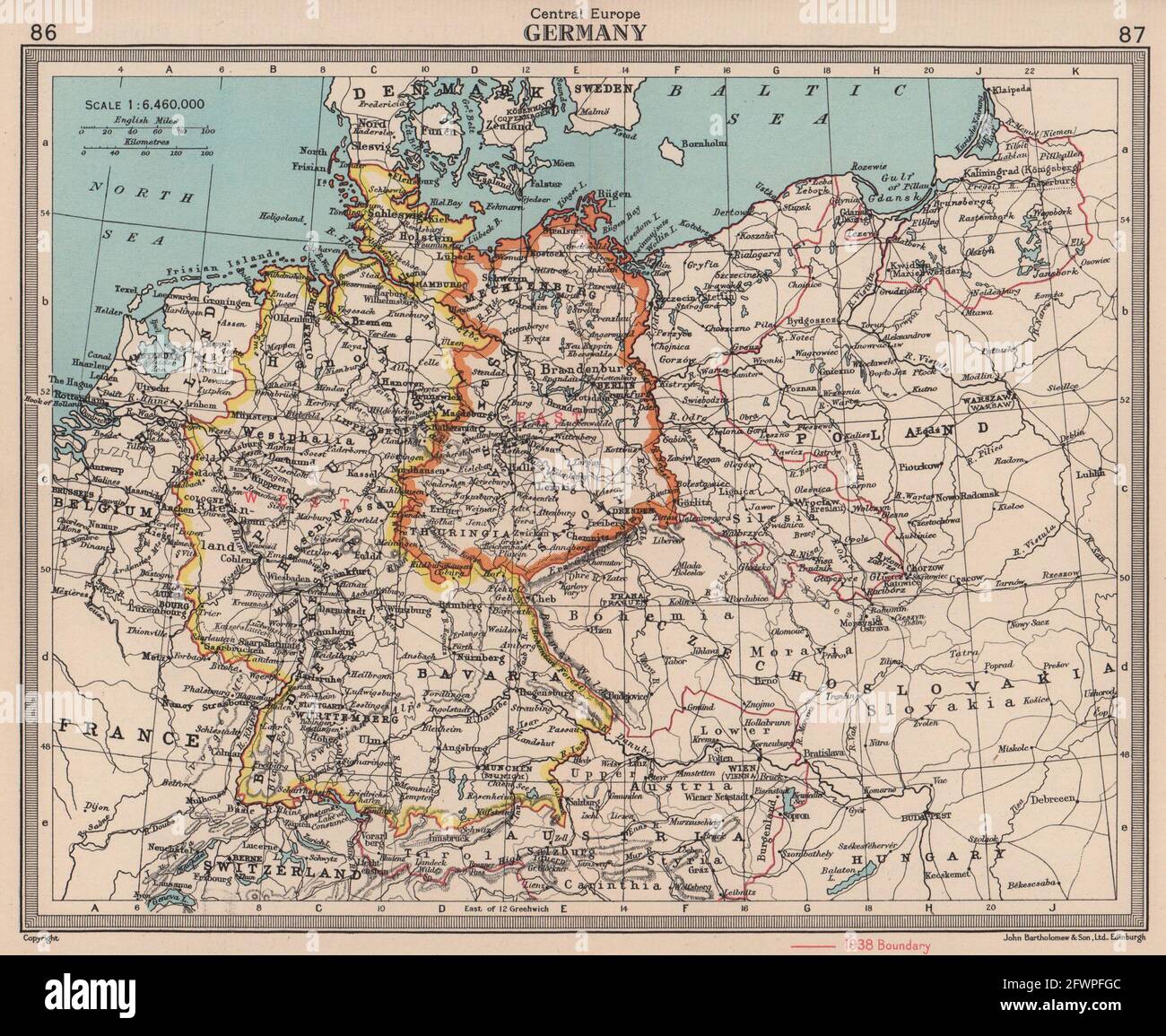

The border wasn’t just a line on paper. It was a 866-mile-long physical scar made of barbed wire, "death strips," and concrete that sliced through the heart of a continent. When you study a map of the era, you aren't just looking at geography; you're looking at the geopolitical manifestation of the Cold War.

The Weird Geography of a Divided Nation

Most people think of the division as a simple 50/50 split. It wasn't. The Federal Republic of Germany (West) was roughly double the size of the German Democratic Republic (East).

If you look at the 1945 occupation zones, the "map" was essentially a compromise between the Four Powers: the US, UK, France, and the Soviet Union. The Soviets took the East, which was traditionally more agricultural and centered around the old Prussian heartlands. The Western allies took the industrial powerhouses of the Ruhr valley and the south.

But then there’s Berlin.

Berlin is the ultimate cartographic headache. It sat deep inside the Soviet zone, like an island in a red sea. To keep it accessible, the Allies had to negotiate specific air corridors and transit routes. If you were a West German driving to West Berlin in 1975, your map would show a very narrow, high-stress "transit motorway" where you weren't allowed to stop for gas or talk to locals. If you broke down, you were in big trouble.

The Inner German Border: More Than Just a Wall

When we talk about the map of East and West Germany, we usually gravitate toward the Berlin Wall. That's a mistake. The "Inner German Border" (die innerdeutsche Grenze) was far more formidable.

🔗 Read more: Lake Nyos Cameroon 1986: What Really Happened During the Silent Killer’s Release

It ran from the Baltic Sea down to the Czechoslovakian border. It wasn't just a fence. It was a sophisticated system of "depth." There was a "Hinterland" fence, then a cleared strip of land, then anti-vehicle trenches, then the actual wall or high-tensile mesh fence. In many places, SM-70 directional mines were rigged to the fences.

Basically, the GDR spent a staggering amount of its national budget just keeping its own people from leaving.

The cartography of the time was also a weapon. East German maps often omitted West Berlin entirely, showing it as a blank white space or labeling it as a "Special Political Entity." On the flip side, West German maps for years refused to recognize the GDR as a country, often labeling the border as a "demarcation line" and keeping the 1937 borders of Germany printed in faint dotted lines to signify that the division was "temporary."

Narrative matters.

Why the Map Still Exists Under the Surface

You’d think after 35 years of reunification, the differences would have evaporated. They haven't. If you overlay a map of modern German property ownership over the old map of East and West Germany, the border reappears instantly.

In the East, the "Junker" estates of the Prussian era were liquidated by the Soviets and turned into state-run collectives (LPGs). When the wall came down, those lands didn't magically go back to small family farmers. Instead, they were often sold off to large agricultural conglomerates. Consequently, farms in the East are huge—often five to ten times the size of the family-run plots you see in Bavaria or Baden-Württemberg.

💡 You might also like: Why Fox Has a Problem: The Identity Crisis at the Top of Cable News

Then there's the wealth gap.

Median net worth for a household in the West is significantly higher than in the East. Why? Inheritances. People in the West had forty years of the Wirtschaftswunder (Economic Miracle) to buy homes and stack stocks. In the East, you didn't "own" your apartment in the same way, and your savings were in Ostmarks, which were converted at a generous but ultimately disruptive rate during the 1990 monetary union.

The Demographic Drain

If you look at a heat map of "missing women," the old border shows up again.

After 1989, there was a massive exodus. But it wasn't just "people" leaving the East; it was specifically young, educated women. They moved to cities like Munich, Hamburg, and Frankfurt for jobs. This left behind a "surplus" of men in many rural Eastern districts. Sociologists like Steffen Kröhnert have pointed out that this demographic imbalance is one of the most extreme in the developed world.

It’s a cartographic tragedy. Entire villages in Saxony-Anhalt or Mecklenburg-Vorpommern essentially aged out of existence.

The "Green Belt" Legacy

Not every remnant of the division is grim. The "Death Strip" has become a "Life Strip."

📖 Related: The CIA Stars on the Wall: What the Memorial Really Represents

Because the border was a no-man's-land for four decades, nature took over. Rare birds, insects, and plants that were being crushed by industrial farming in the rest of Europe found a sanctuary in the border zone. Today, this is the "European Green Belt."

It’s a 1,393 km long nature preserve. You can hike the entire length of the old border. It’s probably the most beautiful way to see the map of East and West Germany today. You’ll walk past old guard towers that have been converted into museums or bat sanctuaries.

What You Should Do Next

If you want to truly understand how this map functions today, don't just look at a political map. Look at these three things:

- Broadband Coverage: The East actually has some of the best fiber-optic potential because they started from scratch in the 90s, while the West is often stuck with aging copper wires.

- Religion: The map of "No Religious Affiliation" almost perfectly mirrors the old GDR borders due to decades of state-sponsored atheism.

- The "Ampelmännchen": When you’re in Berlin, look at the pedestrian walk signals. The East has the cute little guy with the hat; the West has the generic stick figure. It’s the one area where Easterners successfully fought to keep their "map" alive.

To get a real sense of the scale, visit the Point Alpha Memorial on the border between Hesse and Thuringia. It was the place where the Cold War was "hottest"—the Fulda Gap, where NATO expected a Soviet tank invasion to begin. Seeing the tanks and the fences in person makes that line on the map feel terrifyingly real.

Go look at the 2024 election results for the AfD (Alternative for Germany) party. The geographic split is almost 1:1 with the 1989 border. The "Map in the Head" (Mauer im Kopf) is still very much a reality. Understanding this isn't just a history lesson; it's the only way to understand why Germany behaves the way it does in the 21st century.

Actionable Insights for Your Next Trip

- Skip the Checkpoint Charlie tourist traps. It's basically a McDonalds-themed version of history.

- Visit the Tränenpalast (Palace of Tears). It's the actual border crossing at Friedrichstraße station. The feeling of the cramped, clinical booths is still there.

- Drive the B1. This federal highway runs from the Dutch border all the way to the Polish border. It was the old "Reichsstraße 1" and it crosses the former border at the Glienicke Bridge (the "Bridge of Spies").

- Download a "Border Map" Overlay. Use an app that shows your GPS position relative to the 1989 border while you're walking around Berlin; you'll be shocked how often you cross it without realizing.

The division is over, but the map is eternal.