If you look at a vintage map of D-Day today, it looks almost clean. You see those big, colorful arrows—blue for the Allies, red for the Germans—slicing across the English Channel toward the coast of Normandy. It looks like a giant chess match. But honestly? That’s not what it was like at all. The real map, the one used by guys like Omar Bradley or the paratroopers who jumped into the dark over Sainte-Mère-Église, was a messy, terrifying blueprint for what became the largest seaborne invasion in history.

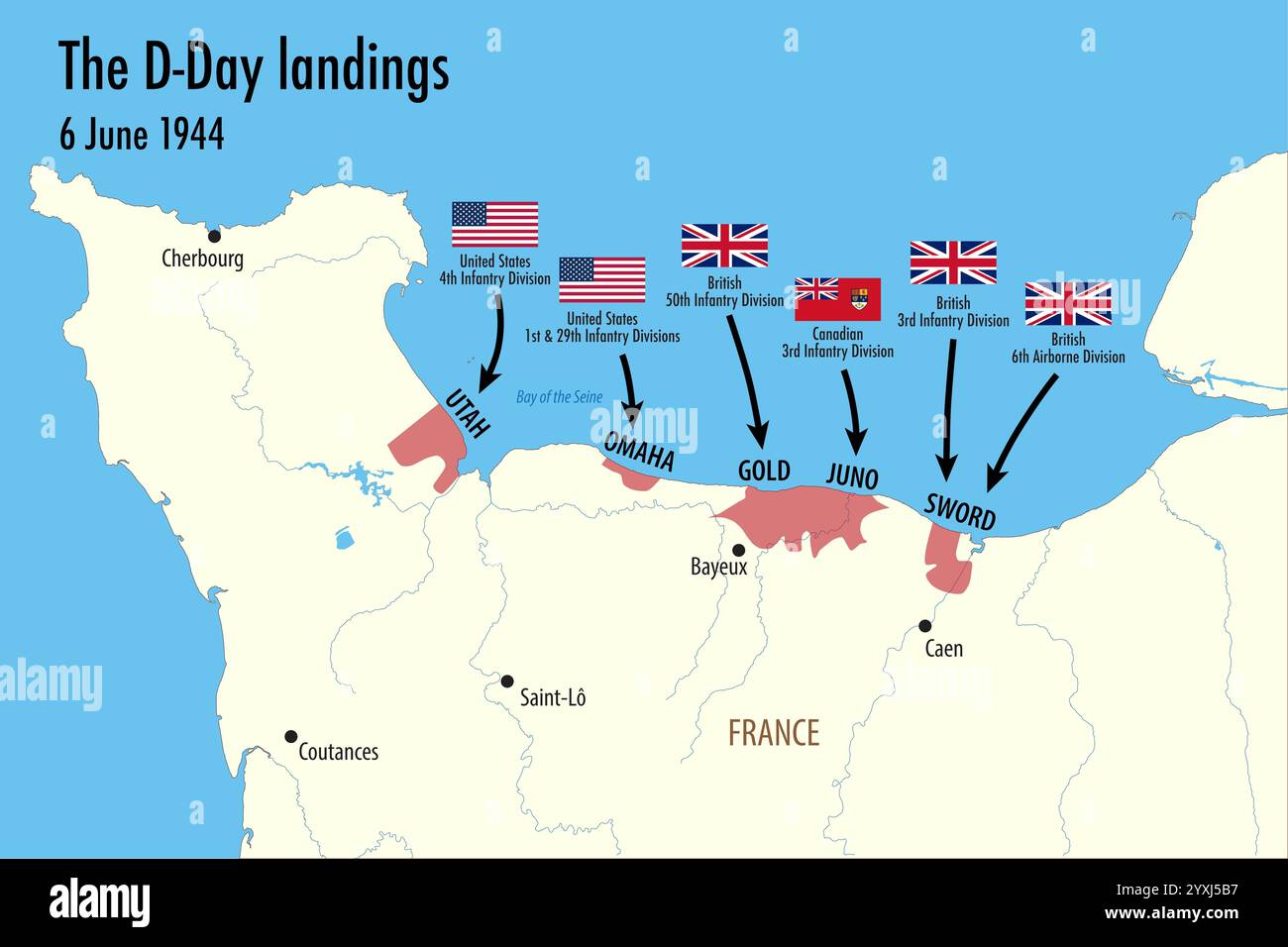

Operation Overlord wasn't just about "hitting the beach." It was a logistical nightmare spread across five specific sectors: Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword. When you study a map of D-Day, you're looking at more than just geography. You're looking at the precise moment the world changed.

The sheer scale is hard to wrap your head around. Over 150,000 troops. Thousands of ships. It wasn't just a line on a page; it was a 50-mile stretch of French coastline that had to be cracked open like an egg.

The Five Beaches: A Map of D-Day Breakdown

Most people think the invasion was one big swarm. It wasn't. The map of D-Day shows a very deliberate, surgical division of labor.

Utah Beach was the westernmost point. It was added late to the planning because the Allies realized they needed a port—specifically Cherbourg—to keep the supplies flowing. If they didn't take Utah, they'd be stuck on the sand with no way to move tanks or fuel inland. The 4th Infantry Division landed here, and weirdly enough, they actually landed in the wrong spot. Strong currents pushed them about 2,000 yards south of their intended target. Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr. realized the mistake, looked around, and famously decided, "We’ll start the war from right here." It turned out to be a lucky break because the defenses there were much weaker.

Then there’s Omaha Beach. This is the one you see in the movies. It’s the "Bloody Omaha" everyone talks about. Looking at the topography on a map of D-Day, you can see why it was a death trap. High bluffs overlooked the entire beach. The Germans, specifically the 352nd Infantry Division, had a bird's-eye view of everything moving on the sand. The map shows the "draws"—five natural valleys that were the only way off the beach. The Germans knew this and zeroed their guns right on those exits.

The British and Canadians took the eastern flank. Gold, Juno, and Sword. The British 50th Division hit Gold.

The 3rd Canadian Division hit Juno.

The British 3rd Division hit Sword.

👉 See also: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

The goal for the British and Canadians was to link up and take the city of Caen. They didn’t get it on day one. Not even close. Caen became a brutal, grinding battle that lasted for weeks. But if you look at the tactical map of D-Day, you see the plan was to create a continuous front, a solid wall of Allied soldiers that the Germans couldn't push back into the sea.

The Terrain You Can't See on a Flat Map

Maps are flat, but Normandy isn't. Just inland from the beaches, the map of D-Day reveals the "Bocage." This is the hedgerow country. These aren't the cute little garden hedges you see in English suburbs. We’re talking about ancient, thick walls of earth and tangled roots, sometimes ten feet high.

For the American paratroopers of the 82nd and 101st Airborne, the map was a mess. They were supposed to drop behind Utah Beach to secure the causeways. But because of clouds and heavy anti-aircraft fire, pilots overshot their marks. Thousands of men were scattered across the flooded marshes of the Merderet and Douve rivers. On a map, these areas looked like solid ground. In reality, they were death traps where heavily laden soldiers drowned in just a few feet of water.

The Germans had deliberately flooded the fields by damming the rivers. This turned the map of D-Day into a labyrinth of narrow roads and underwater obstacles. If you were a paratrooper that night, your map was basically useless the moment you hit the ground. You had to find your unit by clicking "crickets" (metal noisemakers) and hoping the person clicking back wasn't a German with an MG42.

Why the Map of D-Day Still Matters Today

You might wonder why we still obsess over these old charts. It’s because the map of D-Day is a masterclass in deception. Ever heard of Operation Fortitude?

The Allies spent months convincing Hitler that the invasion would happen at the Pas-de-Calais. That’s the narrowest part of the English Channel. They built a "ghost army" of inflatable tanks and fake radio chatter. They even put General George S. Patton—the guy the Germans feared most—in charge of this fake force.

✨ Don't miss: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessing Over Maybelline SuperStay Skin Tint

When you look at a German map of D-Day from early June 1944, their reinforcements were all in the wrong place. They kept their best Panzer divisions near Calais, waiting for an invasion that never came. Even after the landings started in Normandy, Hitler was convinced it was a diversion. He thought the real map of D-Day would be centered on Calais. By the time he realized his mistake, the Allies had a foothold they wouldn't let go of.

Point du Hoc: The Map’s Impossible Vertical

There’s a tiny sliver on the map between Utah and Omaha called Pointe du Hoc. It’s a massive cliff, 100 feet high. Intelligence reports showed the Germans had placed heavy artillery there that could rain fire down on both American beaches.

The map of D-Day tells us the U.S. Army Rangers had to scale those cliffs using ropes and ladders. It sounds insane. It was insane. When they finally reached the top after a brutal climb under fire, they found... nothing. The guns had been moved. The Rangers had to hunt them down in nearby orchards, eventually finding them hidden in a hedgerow, aimed and ready to fire. They destroyed them with thermite grenades. It’s a reminder that even the best maps are only as good as the live intelligence behind them.

Realities of the "Atlantic Wall"

The Germans spent years building the Atlantic Wall. Rommel, the "Desert Fox," was in charge of the defenses. He knew that if the Allies weren't stopped on the beaches, the war was lost.

If you examine a defensive map of D-Day, you’ll see Rommel’s "obstacles."

- Belgian Gates: Massive steel frames designed to tear the hulls out of landing craft.

- Hedgehogs: Those six-pointed metal stars you see in photos.

- Rommel’s Asparagus: Thousands of wooden poles planted in fields to stop Allied gliders from landing.

Rommel wanted the invasion to happen at high tide so the obstacles would be underwater and invisible. The Allies knew this. So, they landed at low tide. This meant the soldiers had to run across 300 to 400 yards of open sand under machine-gun fire, but at least the boats didn't blow up on the way in.

🔗 Read more: Coach Bag Animal Print: Why These Wild Patterns Actually Work as Neutrals

The Mulberry Harbors: Mapping the Impossible

One of the coolest things on a map of D-Day isn't a beach or a town. It's the Mulberries. These were artificial harbors. The Allies knew they couldn't capture a French port like Cherbourg or Le Havre right away. So, they brought their own.

They towed massive concrete blocks across the Channel and sank them to create breakwaters. They built floating piers that rose and fell with the tide. On a map, these look like two tiny cities floating just off the coast of Arromanches and Saint-Laurent. One was destroyed by a massive storm later in June, but the one at Arromanches (Mulberry B) was a lifeline. It allowed the Allies to land over 600,000 tons of supplies in the first 100 days.

How to Read a D-Day Map Like an Expert

If you're looking at a map of D-Day for research or just because you’re a history buff, don't just look at the arrows. Look at the contour lines. Look at the marshlands.

Notice the "limit of advance." Most units didn't reach their D-Day objectives. The map shows where they wanted to be versus where they actually dug in for the night. The 101st Airborne was supposed to have a consolidated zone; instead, they had "pockets" of resistance.

Also, look for the "seams." In warfare, the seam between two units is the weakest point. The map of D-Day shows how the Allies struggled to close the gap between Omaha and Gold beaches. For a while, there was a seven-mile hole in the line. If the Germans had launched a major counter-attack there, the whole invasion might have folded.

Misconceptions About the Map

- It was a "surprise": Well, the location was a surprise, but the Germans knew an invasion was coming. Their maps were marked with "danger zones" all along the French coast.

- The weather was perfect: The map of D-Day originally had a June 5 date. A massive storm pushed it to June 6. General Eisenhower had to make a call during a tiny break in the weather. If they hadn't gone on the 6th, the next window wasn't for two weeks, and by then, the Germans might have figured it out.

- The Navy just sat back: The map shows "fire support areas." Destroyers actually risked running aground at Omaha Beach, coming within 800 yards of the shore to blast German pillboxes that the heavy bombers had missed.

Actionable Steps for Exploring D-Day History

If you want to really understand what happened, a flat image on a screen isn't enough. Here is how you can actually engage with the history of the map of D-Day:

- Use Interactive Geospatial Tools: Sites like the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC) have digital maps that overlay troop movements onto modern satellite imagery. It helps you see exactly where those cliffs at Pointe du Hoc are in relation to the beaches.

- Visit the Overlord Museum: If you ever go to Normandy, go to the Colleville-sur-Mer area. They have original maps used by planners that still have the pencil marks on them. It makes it feel much more human.

- Study the "Bigot" Maps: These were the most top-secret maps of the war. "BIGOT" was a security classification higher than Top Secret. You can find declassified versions online. They show every single German bunker, machine-gun nest, and barbed wire fence known to Allied intelligence.

- Read Personal Memoirs Alongside the Map: Pick up Beyond Band of Brothers by Dick Winters. When he describes the Brécourt Manor Assault, find that spot on a map. Seeing the distance he had to cover makes the tactical genius of that fight much clearer.

- Compare 1944 to Now: Use Google Earth to look at the "draws" at Omaha Beach. Most are now paved roads. Seeing how the terrain has been built over—or preserved—gives you a sense of the scale that a 2D paper map just can't provide.

The map of D-Day isn't just a relic. It’s a record of a million tiny decisions made by people who weren't sure they were going to live through the next hour. When you look at those lines and colors, remember the sweat and the sheer "kinda-sorta" luck that turned a desperate plan into a victory.