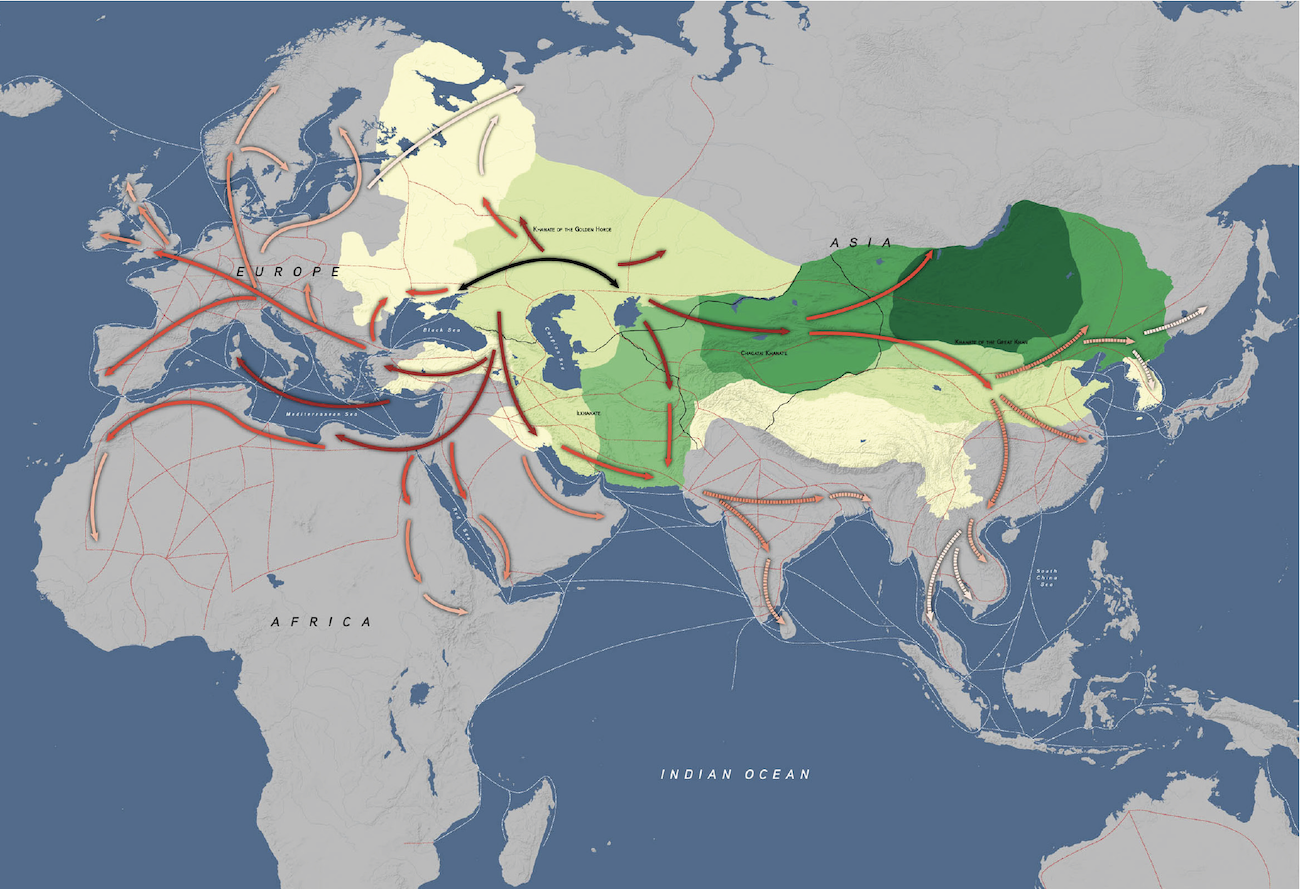

History is usually taught as a series of clean lines on a page. You see a map, you see some arrows, and you think you understand exactly how the world fell apart in the 1340s. But looking at a map of Black Plague spread isn't like tracking a modern flight path. It’s more like watching ink spill across a crumpled tablecloth. It’s jagged. It’s unpredictable. Honestly, it’s a bit of a miracle anyone survived at all.

The Yersinia pestis bacterium didn't just walk from A to B. It hitched rides on grain ships, hid in the fur of marmots, and traveled in the saddlebags of Mongol warriors. When we talk about the "spread," we’re talking about a biological wildfire that consumed roughly 30% to 60% of Europe's entire population in just a few years. That’s not just a statistic. It’s a total civilizational collapse that rewritten the DNA of the Western world.

Where the Map Actually Starts

Most people assume the plague started in China because that’s what the older textbooks say. It’s a bit more complicated than that. Recent genomic studies, including the massive 2022 study published in Nature by researchers like Maria Spyrou, point toward Central Asia—specifically modern-day Kyrgyzstan. They found the "source" strain in graves near Lake Issyk-Kul.

From there, it followed the Silk Road. It wasn't a sudden burst. It was a slow creep. By 1346, it reached the Crimean Peninsula. This is where the story gets legendary, if a bit grim. The Siege of Caffa is often cited as the first instance of biological warfare. The Golden Horde, suffering from the plague, allegedly catapulted infected corpses over the city walls. Did it actually happen that way? Chronicler Gabriele de' Mussi swore it did. Whether the catapults were the main cause or if rats simply slipped through the gates, the result was the same. The plague had found a port. And once it hit the water, the map of Black Plague spread exploded.

The Maritime Expressway

Genoese galleys fled Caffa. They were "death ships." By the time they hit Messina, Sicily, in October 1347, most of the sailors were either dead or leaking black pus from their armpits. The locals kicked them out, but it was too late. The fleas had already jumped ship.

📖 Related: Why the EMS 20/20 Podcast is the Best Training You’re Not Getting in School

Once the plague hit the Mediterranean, it used the trade routes like a high-speed rail network. It hit Constantinople. It hit Marseille. It hit Pisa. If you look at the map of Black Plague spread during 1348, you see these weird leaps. It didn't move in a circle; it jumped from port to port, then bled inland.

Why did some places get hammered while others stayed safe? Look at Milan. They basically stayed "plague-free" for a long time by bricking up the doors of houses where the infection was found. Extreme? Yes. Effective? Kinda. Meanwhile, in Florence, Boccaccio wrote that people dropped dead in the streets like flies. He estimated 100,000 deaths in that city alone, though historians think that might be a bit of an exaggeration for dramatic effect. Still, the trauma was real.

The Weird Gaps in the Map

If you look closely at a detailed map of Black Plague spread, you’ll notice these "holes." Parts of Poland, Westphalia, and the mountainous regions of the Pyrenees seem largely untouched in the 1340s.

Historians argue about why. Was it low population density? Maybe. Was it because they had fewer trade links? Probably. Or maybe the local rats just weren't the right kind of hosts. It shows that geography was the only real "vaccine" people had back then. If you were isolated, you lived. If you were at the center of the world, you were in trouble.

👉 See also: High Protein in a Blood Test: What Most People Get Wrong

The Northern Crawl and the Second Wave

By 1349, the plague had crossed the English Channel. It’s weird to think about, but the plague actually traveled slower on land than by sea. It moved maybe a mile or two a day through the countryside. But in London, the density was a nightmare.

The map of Black Plague spread shows it reaching Scandinavia and even Greenland by 1350. There’s a heartbreaking theory that the plague is what finally killed off the Norse settlements in Greenland. They were already struggling with a cooling climate, and then the supply ships from Europe stopped coming—or they arrived with infected rats.

Why the Map Keeps Changing

We used to think it was all about the Black Rat (Rattus rattus). Now, scientists are looking at human ectoparasites—basically, lice and fleas on people, not just rats. A 2018 study from the University of Oslo suggested that human-to-human transmission via fleas was actually the main driver of the fastest-moving parts of the map.

This changes everything. It means the plague didn't need a massive rat population to decimate a city. It just needed a crowded marketplace.

✨ Don't miss: How to take out IUD: What your doctor might not tell you about the process

What We Can Actually Learn from the Data

Looking at these maps isn't just a history lesson. It’s a lesson in connectivity. The Black Death was the first truly global pandemic because it was the first time the world was sufficiently "connected" by trade to allow a germ to travel thousands of miles.

The social fallout was massive:

- Labor shortages: So many peasants died that the survivors could demand higher wages. This basically ended feudalism.

- Medical shifts: Doctors realized that Galen’s ancient theories about "humors" were useless. They started looking at actual observation.

- Religious upheaval: People saw that the plague killed priests just as fast as sinners. It started a long, slow slide toward the Reformation.

The plague never really went away, either. It stayed in the soil or in rodent populations, popping up every few decades for centuries. The Third Pandemic in the 1800s started in China and hit San Francisco. Even today, you can find plague in prairie dogs in the American Southwest.

Actionable Insights for Geography and History Enthusiasts

If you're trying to track historical pandemics or understand how geography shapes health, here is how you can practically apply this knowledge:

- Consult Primary Cartography: Don't just look at modern recreations. Check digital archives like the British Library for 14th-century maps to see how people at the time perceived their world versus where the disease actually was.

- Use GIS Tools: If you're a student or researcher, use Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to overlay 14th-century trade routes with modern topographical maps. You'll see how river valleys and mountain passes dictated the speed of the spread.

- Verify Source Strains: When reading about plague "maps," always check if the data is based on archeological finds (DNA from teeth) or just old church records. DNA evidence is the gold standard for modern accuracy.

- Contextualize Local History: Check your own local history for "Plague Pits" or "Pest Houses." Many European cities still have parks or squares that are actually mass graves from the 1340s. Understanding the physical site makes the map much more visceral.