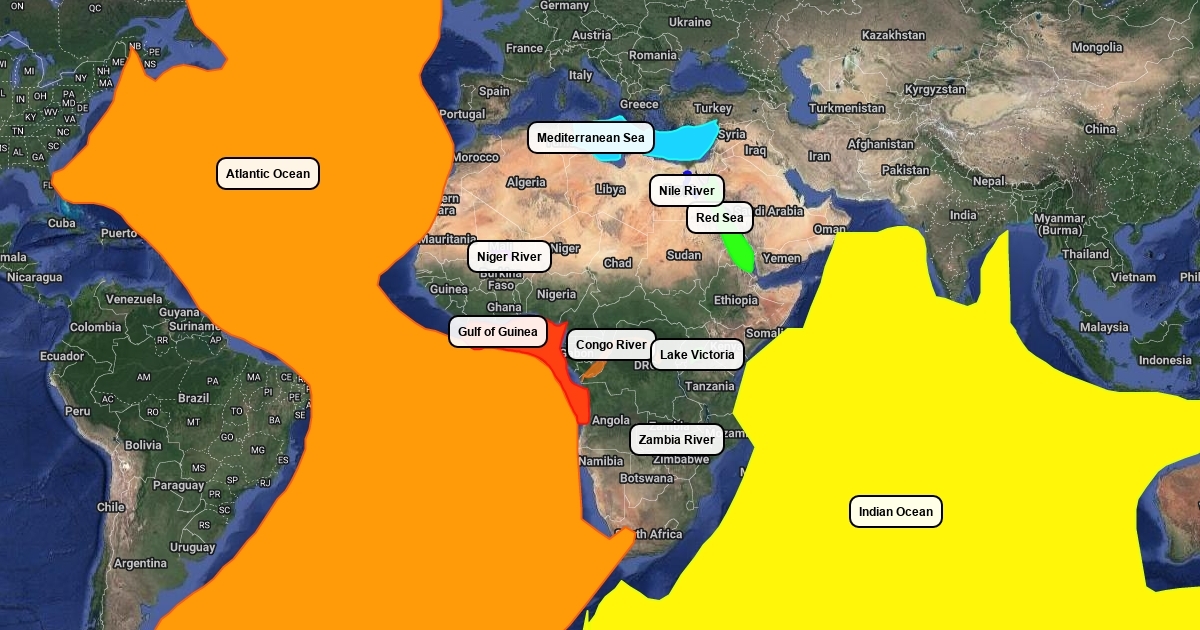

Look at any map of Africa with bodies of water and you’ll see it immediately. The continent isn't just a massive block of land. It’s a literal island on a global scale, hugged by the Atlantic to the west and the Indian Ocean to the east. But the real story is inside. The veins. The massive, sprawling basins that define where people live, where wars are fought, and where the world’s climate actually begins its messy dance.

Honestly, most school maps do a terrible job of showing how much water dominates the African landscape. They give you a blue squiggle for the Nile and maybe a blob for Lake Victoria. Then they stop. But if you're trying to understand why Cairo exists or why the Congo Basin is the "second lung" of the earth after the Amazon, you need to look closer at the hydrologic reality. Africa is thirsty, yet it sits on some of the most significant freshwater reserves on the planet. It’s a paradox.

The Big Three: Rivers That Define a Continent

If you’re looking at a map of Africa with bodies of water, the Nile is usually the first thing your eyes gravitate toward. It’s long. Roughly 6,650 kilometers long, though Brazilian researchers have argued the Amazon might actually be longer depending on where you start measuring. The Nile is weird because it flows north. That messes with people's heads sometimes. It starts in the highlands of East Africa and the mountains of Ethiopia, merging at Khartoum before slicing through the Sahara like a green ribbon. Without that specific water source, Egypt simply doesn't exist as a civilization. It's that simple.

Then you have the Congo River. This thing is a beast. While the Nile is long, the Congo is deep—the deepest in the world, hitting depths of over 220 meters. It carries so much water that it colors the Atlantic Ocean for miles beyond the river's mouth. When you see it on a map, it looks like a giant fan spreading across Central Africa. It’s the only major river to cross the equator twice. Think about that for a second. The humidity and the sheer volume of discharge make it the heartbeat of the African rainforest.

The Niger River is the third heavy hitter. It does this bizarre "boomerang" shape. It starts near the Atlantic, flows away from it into the Sahara desert, and then hooks a hard right to dump back into the Gulf of Guinea. Why? Because it’s actually two ancient rivers that joined together thousands of years ago. It’s a geographical accident that allows millions of people in Mali and Niger to survive in the Sahel.

Why the Great Lakes Region is Basically an Inland Sea

Most people think of the Great Lakes and immediately picture Michigan or Superior. But the African Great Lakes system is arguably more dramatic. It’s formed by the East African Rift, where the continent is literally tearing itself apart.

📖 Related: Hairstyles for women over 50 with round faces: What your stylist isn't telling you

Lake Victoria is the celebrity here. It’s the largest tropical lake in the world. But it’s surprisingly shallow. If you drained it, it would look more like a massive puddle compared to Lake Tanganyika. Now, Tanganyika is the real outlier. It’s the second-deepest lake on earth. It holds nearly 19% of the world’s available freshwater. It’s so deep and so old that it has evolved its own unique ecosystem of cichlid fish that you won't find anywhere else.

Breaking Down the Major Lakes

- Lake Victoria: Bordered by Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania. It's the primary source of the White Nile.

- Lake Tanganyika: A long, thin finger of water stretching between four countries. It's basically an ocean in the middle of a continent.

- Lake Malawi: Known for having more fish species than any other lake in the world. It's a biodiversity hotspot that looks like a postcard but functions as a vital food source.

- Lake Chad: This is the sad part of the map of Africa with bodies of water. Since the 1960s, it has shrunk by about 90%. What used to be a massive inland sea is now a series of marshes, mostly due to irrigation demands and shifting climate patterns.

The Salt Water Borders

Africa is surrounded by four distinct bodies of water, and each one dictates the climate of the coastal countries.

The Mediterranean Sea to the north is the historical bridge to Europe. It's calm, relatively warm, and helped facilitate the trade of the ancient world. Then you have the Red Sea to the northeast. It’s one of the saltiest and warmest bodies of water on the planet because there’s almost no river runoff flowing into it. It’s a volcanic trench, essentially.

On the west, the Atlantic Ocean brings the cold Benguela Current up from the south, which is why the Namib Desert is so dry despite being right next to the ocean. The moisture just doesn't evaporate into rain there. On the east side, the Indian Ocean is much warmer, fueling the monsoon rains that provide water for East African agriculture.

Hidden Waters: The Aquifers

Here is what isn't on your standard map of Africa with bodies of water: the groundwater. Underneath the Sahara Desert lies the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System. It is the world's largest known "fossil" water aquifer. We’re talking about water that was trapped underground thousands of years ago when the Sahara was green and lush.

👉 See also: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

Libya’s "Great Man-Made River" project actually taps into this. It’s a massive network of pipes that brings water from the middle of the desert to the coastal cities. It’s controversial because that water isn’t being replaced. Once it’s gone, it’s gone. It’s essentially mining for water instead of gold or oil.

The Geopolitics of the Blue Lines

Water in Africa isn't just for looking at. It’s a source of massive tension. Take the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Ethiopia built it on the Blue Nile to generate electricity. Egypt is terrified because they think it will restrict their water supply. When you look at the map, you see the line of the river connecting them, but you don't see the diplomatic cables and threats being traded over who owns that flow.

The Zambezi River in the south is another powerhouse. It’s famous for Victoria Falls—the "Smoke that Thunders"—but it’s also the backbone of energy for Zimbabwe and Zambia through the Kariba Dam. When the water levels drop there, the lights go out in the cities.

Actionable Insights for Navigating African Geography

If you are studying or traveling through these regions, keep these practical points in mind:

1. Respect the Nile's seasonal shifts. If you’re in Sudan or Egypt, the river’s height varies. Even with dams, the local ecology and agriculture are tied to the flow cycles. Don't assume the river looks the same in August as it does in February.

✨ Don't miss: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

2. Lake safety is real. The African Great Lakes are prone to sudden, violent storms. Because they are so large, they create their own weather patterns. If you're on a ferry on Lake Victoria, check the local forecasts religiously.

3. Recognize the "Water Gap." When looking at a map, notice where the water isn't. The Kalahari and Sahara are defined by the absence of surface water, but they often have deep wells. If you’re planning a route through the interior, your path will almost always be dictated by "wadis" (seasonal riverbeds) or permanent boreholes.

4. Malaria and Water. Bodies of water in tropical Africa are breeding grounds for mosquitoes. If you are near the Congo Basin or the Great Lakes, the proximity to water directly correlates with the need for malaria prophylaxis and heavy-duty netting.

5. Hydropower vs. Fishing. Be aware that many of Africa's lakes are artificial. Lake Volta in Ghana is one of the largest man-made lakes in the world. It provides power but also changed the entire local economy from land-based to fishing-based.

The map is a living document. Rivers change course, lakes shrink, and new dams create massive reservoirs that didn't exist fifty years ago. To truly understand the map of Africa with bodies of water, you have to stop seeing the blue parts as static and start seeing them as the moving, breathing lungs of the continent.