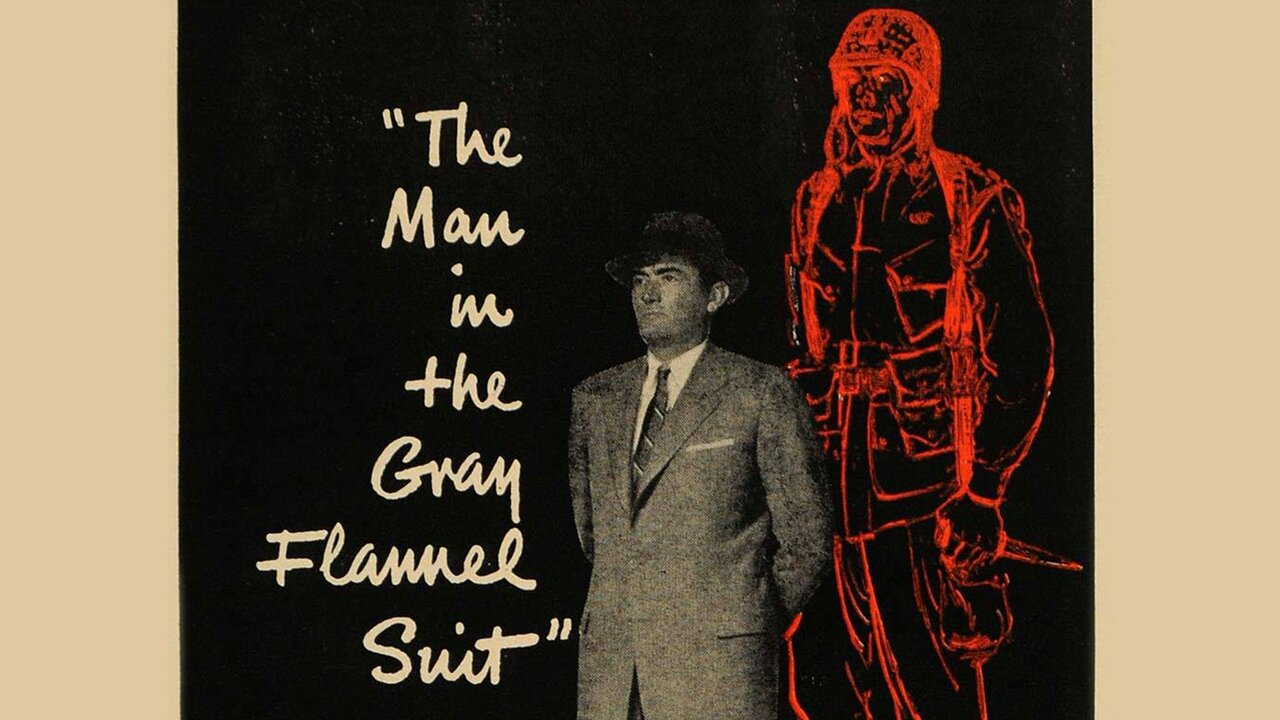

You’ve seen the image. A sea of commuters, all wearing the same charcoal suit, marching toward Grand Central with the same blank expression. It’s the ultimate cliché of 1950s soul-crushing conformity. But honestly? If you think The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit is just some dusty relic about guys in hats, you’re missing the point. It’s actually about us. Right now.

The 1955 novel by Sloan Wilson—and the subsequent Gregory Peck movie—didn't just capture a moment in time. It captured a permanent glitch in the human software: the trade-off between a "good life" and a "real life."

What Most People Get Wrong About the Flannel Suit

Most folks assume this story is a critique of the "boring" fifties. They think it’s about men who wanted to be robots. That is 100% wrong. Tom Rath, the protagonist, didn't want to be a cog. He was a paratrooper in World War II. He had seen people die. He had killed people. He was vibrating with what we’d now call PTSD, trying to figure out why he was sitting in a skyscraper arguing about broadcasting rights when he used to be a warrior.

The "gray flannel suit" wasn't a fashion choice. It was camouflage.

It was a uniform for men who were desperate for stability after a decade of global chaos. When you've spent years in a foxhole, a 9-to-5 with a pension looks like heaven. Until it doesn't. The conflict isn't about the suit; it’s about the fact that Tom Rath is a "decent but struggling" guy who realizes that the corporate ladder is just another type of war, only this one has less honest rules.

The United Broadcasting Corporation and the Myth of "Hard Work"

In the book, Tom lands a job at the fictional United Broadcasting Corporation (UBC). He’s working for Ralph Hopkins, a high-powered CEO who is basically the archetype for every workaholic tech founder we see today. Hopkins is successful, wealthy, and powerful. He’s also miserable. His daughter is a rebel, his wife is a stranger, and he has no hobbies.

🔗 Read more: Nick's Manhattan Beach Photos: Why the Lighting Here is a Local Secret

Here is the kicker: Hopkins isn't the villain.

That’s what makes Wilson’s writing so nuanced. Hopkins is actually a pretty decent guy who just happens to be a slave to his own ambition. He expects Tom to be the same. There’s a specific scene where Tom has to write a speech for Hopkins. He realizes he can either tell the truth and potentially get fired, or tell the boss what he wants to hear and get promoted.

Tom chooses a third path: honesty. He tells Hopkins the speech is garbage.

It’s a risky move. It’s the kind of move we all wish we had the guts to make in a Slack channel today. Surprisingly, Hopkins respects him for it. But that respect comes with a price—the expectation of total soul-ownership.

Why 1955 Looks a Lot Like 2026

You might be sitting there in joggers instead of flannel, but the pressure is identical. The "suit" has just become digital. Instead of a physical uniform, we have "personal brands." Instead of the 5:32 train to Connecticut, we have the "always-on" expectation of a smartphone.

Sloan Wilson was writing about the "organization man." This was a concept popularized by William H. Whyte around the same time. The idea was that the American middle class had stopped being rugged individuals and started being team players who valued "belonging" over "achieving."

Does that sound familiar?

Think about corporate culture today. The "we are a family" slogans. The forced fun. The "culture fit" interviews. These are just modern variations of the gray flannel suit. We are still terrified of being the odd one out. We still trade our best hours for a sense of security that, as we’ve seen with recent mass layoffs in the tech sector, is often an illusion.

The War We Don't Talk About

One thing the movie version softens—but the book hammers home—is Tom’s wartime experience. He killed seventeen men. He had an affair in Italy and fathered a child he never saw again.

The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit is secretly a war novel.

The struggle Tom feels in his suburban house in Connecticut isn't because the grass is long or the neighbors are nosy. It's because he's trying to reconcile the "hero" version of himself with the "husband" version. He feels like a fraud. He’s living a life paid for by a "blood money" inheritance (a complicated plot point involving his grandmother’s estate and a crooked caretaker) and he’s haunted by the ghosts of his past.

This is the E-E-A-T (Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, Trustworthiness) of the story. Wilson wasn't guessing; he was a Coast Guard officer during the war. He knew the specific flavor of "post-war malaise." He knew what it felt like to come home to a world that wanted you to forget everything you’d just done and just focus on buying a new washing machine.

Let's Talk About Betsy

Tom’s wife, Betsy, often gets a bad rap as the "nagging housewife." But if you actually read the text, she’s the engine of the story. She’s the one pushing Tom to get the better job, not because she’s greedy, but because their house is literally falling apart. They have a "crack in the wall" that symbolizes their crumbling stability.

Betsy is the one who has to handle the revelation of Tom’s illegitimate Italian son. Her reaction isn't a 1950s caricature of a fainting spell. It’s a messy, angry, deeply human struggle toward forgiveness. She pushes Tom to send money to the boy. She chooses morality over appearances.

In a world of gray flannel, Betsy is the one who insists on color, even when that color is a painful shade of truth.

The Ending That No One Expects

In most modern corporate thrillers, the hero either burns the building down or becomes the CEO. Tom Rath does neither.

He turns down the big promotion.

He tells Hopkins that he doesn't want to be a "big man" if it means never seeing his kids. He chooses "enough."

"I don't think I'm the kind of guy who should try to be a big shot," Tom says. It’s one of the most radical sentences in American literature. We are conditioned to think that turning down power is a failure. Wilson argues it’s the only way to stay human.

The book ends with Tom and Betsy heading toward a modest, quiet future. It isn't a fairy tale. The crack in the wall is still there. But they’ve decided to stop pretending.

✨ Don't miss: Donald Trump Water Bottle: What Most People Get Wrong

How to Apply "The Flannel Suit" Logic to Your Life

If you’re feeling the weight of your own version of the suit, there are actual, tangible ways to navigate out of it without quitting your job tomorrow and moving to a commune.

- Audit your "Performative Yeses." Tom Rath almost ruined his life by saying yes to things he hated just to look the part. Identify one task this week you're doing solely for optics and see what happens if you do it with "adequate" effort instead of "heroic" effort.

- Define "Enough." The tragedy of Ralph Hopkins was that he had no finish line. He didn't know how much money or power was sufficient. Write down your "enough" number. Once you hit it, stop trading your time for more.

- Separate Identity from Uniform. You are not your job title. Tom Rath realized he was a father, a veteran, and a husband before he was a technical writer for UBC. When you close your laptop, the "suit" should come off completely.

- Acknowledge the Ghosts. We all have "war stories"—past failures, traumas, or secrets that make the mundane world feel surreal. Stop pretending they don't affect your work. Radical honesty (with yourself, if not your boss) is the only cure for the feeling of being a fraud.

The "gray flannel suit" is an opt-in lifestyle. We think it’s forced on us by "the system," but as Tom Rath discovered, the system only has power over you if you want what it’s selling. If you decide you want your soul more than a corner office, the suit suddenly starts to feel a lot lighter.

Sloan Wilson’s masterpiece isn't a warning about the 1950s. It’s a roadmap for 2026. It’s a reminder that you can be "in" the world of business without being "of" it. You can wear the suit when you have to, as long as you know exactly who is underneath it.

Next Steps for Your Career Health

To truly break the cycle of "flannel suit" burnout, you need to conduct a Values Alignment Audit. List your top five life priorities (e.g., family, creativity, health). Then, look at your calendar for the last two weeks. If 80% of your time is spent on things that don't touch those five priorities, you aren't just working a job—you're losing your identity. Start by reclaiming one hour each morning for a "non-negotiable" personal priority before you open your email. This small boundary is the first step in ensuring the suit doesn't wear you.