If you think of James Stewart, you probably picture the stuttering, idealistic hero of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. Or maybe the whimsical guy befriending a giant invisible rabbit in Harvey. But in 1955, Stewart went to a very dark place. He teamed up with director Anthony Mann for the fifth and final time in their legendary Western run to create The Man from Laramie. It wasn’t just another cowboy movie. Honestly, it was a psychological wrecking ball that changed how audiences saw "Jimmy" forever.

The film is brutal. It’s gritty. It feels more like a Shakespearean tragedy—specifically King Lear—than a standard shoot-'em-up. While the 1950s were flooded with Westerns, this one sticks in your brain because it’s obsessed with things like vengeance, legacy, and a very literal kind of pain.

The Plot That Most People Get Wrong

People often remember this as a simple revenge story. It's not. Stewart plays Will Lockhart, an enigmatic stranger who rolls into the isolated town of Coronado. He’s delivering supplies, but that’s just a front. He’s actually an undercover Army captain looking for the people who sold repeating rifles to the Apaches—the same rifles used to massacre his brother’s cavalry troop.

Coronado is run by Alec Waggoman (played by the incredible Donald Crisp), a cattle baron who is slowly going blind. This is where the King Lear vibes kick in. Waggoman has a psychotic, insecure son named Dave (Alex Nicol) and a loyal but resentful foreman, Vic Hansbro (Arthur Kennedy).

The tension in The Man from Laramie isn't just about gunfights. It’s about the rotting family dynamic of the Waggomans. When Lockhart arrives, he’s a catalyst. He’s the grit in the oyster. Dave Waggoman is a spoiled brat with a hair-trigger temper, and his first encounter with Lockhart involves dragging him through a fire and killing his mules. It’s uncomfortable to watch. Stewart’s performance shifts from calm professionalism to a vibrating, high-strung rage that feels genuinely dangerous.

Why the Cinestage Tech Changed Everything

This was one of the first Westerns filmed in CinemaScope, but Mann didn't use the wide frame for just pretty postcards of the New Mexico landscape. He used it to isolate people.

The filming took place around Santa Fe and the Bonanza Creek Ranch. If you look at the shots of the salt flats, they feel endless. Mann and cinematographer Charles Lang used that horizontal space to show how small and vulnerable these "tough" men actually were. They weren't masters of the wilderness; they were ants crawling across a giant, indifferent rock.

💡 You might also like: How to Watch The Wolf and the Lion Without Getting Lost in the Wild

The Scene Everyone Remembers (And Why It Was Shocking)

You can't talk about The Man from Laramie without talking about "the hand scene."

In 1955, onscreen violence was usually clean. A guy gets shot, he clutches his chest, and he falls over. But Dave Waggoman doesn't just shoot Lockhart. His men hold Lockhart down, and Dave shoots him through the palm of his hand at point-blank range.

It’s a horrific moment.

Stewart’s reaction—that guttural, strangled cry—wasn't the kind of thing "America's Sweetheart" was supposed to do. It stripped away the myth of the invincible cowboy. It showed that violence has physical, lasting consequences. Even today, watching that scene makes you flinch. It’s a masterclass in using sound and close-ups to create visceral discomfort.

Stewart and Mann: The Partnership That Broke the Mold

Before they worked together, James Stewart’s career was in a bit of a slump post-WWII. He had come back from the war a different man—he had seen real combat as a bomber pilot, and he couldn't just go back to playing the "aw-shucks" boy next door.

Anthony Mann saw that.

📖 Related: Is Lincoln Lawyer Coming Back? Mickey Haller's Next Move Explained

Starting with Winchester '73 and ending with The Man from Laramie, they made five Westerns that redefined the genre. These films are often called "The Mann-Stewart Westerns," and they are characterized by:

- A hero who is driven by an obsession (usually revenge).

- A landscape that reflects the character's internal state (mountains, salt flats, storms).

- A climax that usually involves a grueling physical struggle.

In this film, Lockhart isn't a "good" guy in the traditional sense. He’s a man possessed. He’s willing to burn down a whole town to find out who killed his brother. This complexity paved the way for the "anti-hero" era of the 1960s and 70s. Without Lockhart, we might not have the gritty protagonists of Sergio Leone or Sam Peckinpah films.

Factual Nuances: The Cast and the Script

The script was based on a story by Thomas T. Flynn, which originally appeared in The Saturday Evening Post. It’s tight. There isn’t a lot of wasted breath.

Arthur Kennedy, who plays Vic, is the secret weapon of the movie. Kennedy was a specialist at playing "the guy you almost like." His Vic is someone who has worked his whole life for a father figure who will never love him as much as his biological son. You almost feel bad for him—until you don't. That ambiguity is what makes the film a cut above the standard black-hat vs. white-hat tropes of the era.

Then you have Cathy O'Donnell as Barbara Waggoman. Often, women in 50s Westerns were just there to be rescued or to provide a "civilizing" influence. Barbara is smarter than that. She’s the moral compass, but she’s also realistic about the violence surrounding her.

The Mystery of the Repeating Rifles

A lot of the plot hinges on the discovery of the repeating rifles. This was a common trope in Westerns—the "corrupt trader" selling guns to Native Americans—but Mann treats it with a level of detective-like scrutiny. Lockhart isn't just looking for a villain; he’s following a trail of logistics.

👉 See also: Tim Dillon: I'm Your Mother Explained (Simply)

Interestingly, the film deals with the Apaches more as a looming, unseen force of nature rather than caricatured villains. The real evil in the movie is internal. It’s the greed of the white settlers and the dysfunction of the Waggoman empire. The "enemy" is just a customer for the guns that the "civilized" men are selling.

Modern Misconceptions and Legacy

Some modern viewers find the pacing of 1950s Westerns a bit slow. If you’re used to John Wick, the build-up might feel long. But that’s the point. The Man from Laramie is a slow-burn pressure cooker.

One common misconception is that this was just a "color version" of Stewart’s earlier Westerns. It’s actually much more cynical. By 1955, the Stewart/Mann partnership was reaching its breaking point. In fact, they had a falling out shortly after this during the production of Night Passage, and they never worked together again. You can almost feel that tension on the screen. There’s a weariness in Stewart’s eyes that wasn’t there in Winchester '73.

The film also avoids the "happily ever after" trope. While there is a resolution, it’s a somber one. People are dead. Families are destroyed. The hero doesn't necessarily get "peace"; he just gets the job done.

Actionable Insights for Cinephiles

If you want to truly appreciate The Man from Laramie, don't just watch it as a popcorn flick. Watch it as a psychological study.

- Watch the eyes. Pay close attention to Donald Crisp’s performance as he goes blind. The way he uses his voice and hands to compensate for his failing sight is a masterclass in acting.

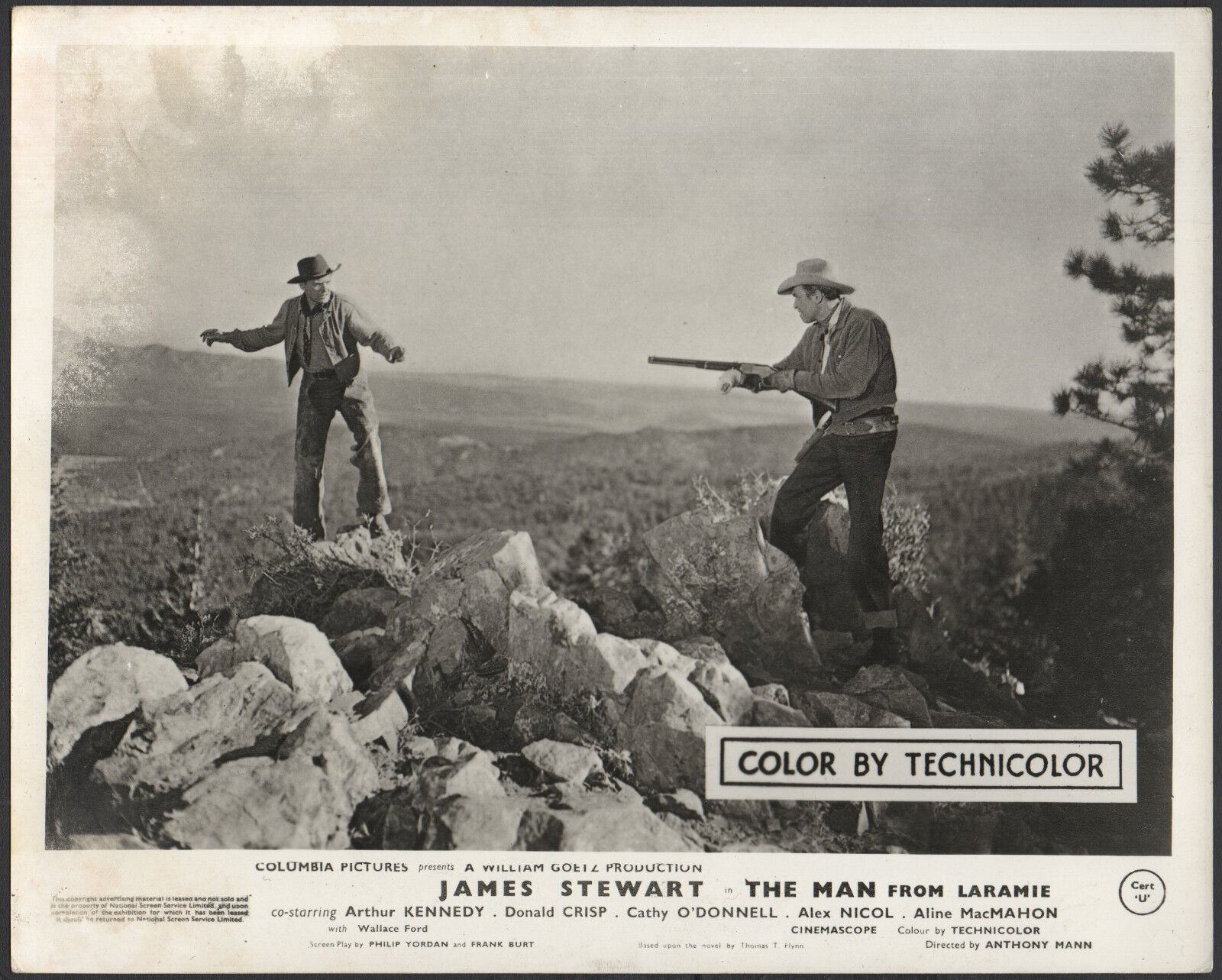

- Analyze the verticality. Anthony Mann loved putting his characters in high places—cliffs, mountains, ridges. In the final confrontation, look at how the height differences between characters signify who has the moral or physical upper hand.

- Compare it to King Lear. If you’re a fan of literature, map out the characters. Alec is Lear, Dave is the reckless heir, and Vic is the loyal servant who is eventually corrupted by the lack of recognition.

- Check the score. George Duning’s music is sweeping, but notice when the music stops. Mann uses silence and ambient wind noise during the most violent moments to make them feel more "real."

- Double feature it. To see the evolution of the genre, watch this back-to-back with John Ford’s The Searchers (1956). Both films feature a legendary leading man (Stewart and Wayne) playing a character driven by a dark, obsessive quest. It highlights the mid-50s shift toward the "Psychological Western."

The Man from Laramie remains a high-water mark for the genre because it refused to play it safe. It took a beloved American icon and put him through the ringer, both physically and emotionally. It’s a film about the weight of the past and the impossibility of true justice. It’s not just a Western; it’s a piece of American tragedy filmed in glorious Technicolor.

If you're diving into Stewart's filmography, this is the essential bridge between his early charm and the obsessive, haunted characters he would later play for Alfred Hitchcock in Vertigo. You can see the seeds of Scottie Ferguson in Will Lockhart’s cold, determined eyes.

To get the most out of your viewing, seek out the 4K restoration if possible. The depth of the New Mexico landscape and the detail in the weathered faces of the cast deserve the highest resolution available. It turns a "small" story of a man and his brother into a sprawling, cinematic epic that still feels modern seventy years later.