Think of a knight. You’re probably picturing a longsword, right? Gleaming steel, sharp edges, the whole romantic deal. But honestly, if you were actually standing on a 14th-century battlefield facing a guy in full plate armor, that sword would be about as useful as a butter knife. You’d want a mace.

A mace is, at its simplest, a stick with a heavy, reinforced head. It’s a blunt force trauma machine. While swords were busy getting stuck in gaps or snapping against hardened steel, the mace was busy turning internal organs into jelly without needing to find a single weak point in the armor. It's the ultimate "anti-meta" weapon of history.

The Brutal Physics of What is a Mace

We need to get one thing straight: the mace didn't evolve because people liked being crude. It evolved because armor got too good. By the time the High Middle Ages rolled around, maille (chainmail) and early plate armor were making slashing weapons obsolete. If you hit a guy in a breastplate with a sword, the sword bounced.

The mace changes the math.

Instead of trying to cut through the steel, a mace uses kinetic energy to bypass it. When that heavy iron head hits a helmet, the helmet might not even break, but the brain inside definitely stops working. It’s about percussive force. You’re sending a shockwave through the equipment and directly into the person. Ewart Oakeshott, the legendary historian of arms and armor, noted that the mace was the primary solution to the "armor problem" for centuries.

It’s essentially a specialized hammer. But unlike a hammer you’d use to hang a picture, a mace is balanced for a swing that generates maximum torque. The weight is concentrated entirely at the end of the shaft. This makes it top-heavy and difficult to recover if you miss, but devastating if you connect.

From Tree Branches to Flanged Steel

The mace is arguably the oldest weapon in human history. Seriously. Before we figured out how to sharpen flint or smelt bronze, we figured out that hitting something with a heavy stick worked pretty well.

💡 You might also like: Bootcut Pants for Men: Why the 70s Silhouette is Making a Massive Comeback

The earliest versions were just clubs. Eventually, humans got "clever" and started sticking rocks into the ends of those clubs using leather thongs or resin. We’ve found pear-shaped mace heads in Egypt dating back to the Predynastic period—long before the pyramids were even a thought. These weren't just for show; they were used to crush skulls in localized tribal conflicts.

As metallurgy improved, so did the mace.

- The Bronze Age: Maces became status symbols. They were often cast in intricate shapes, though bronze is a bit brittle for sustained heavy impact compared to what came later.

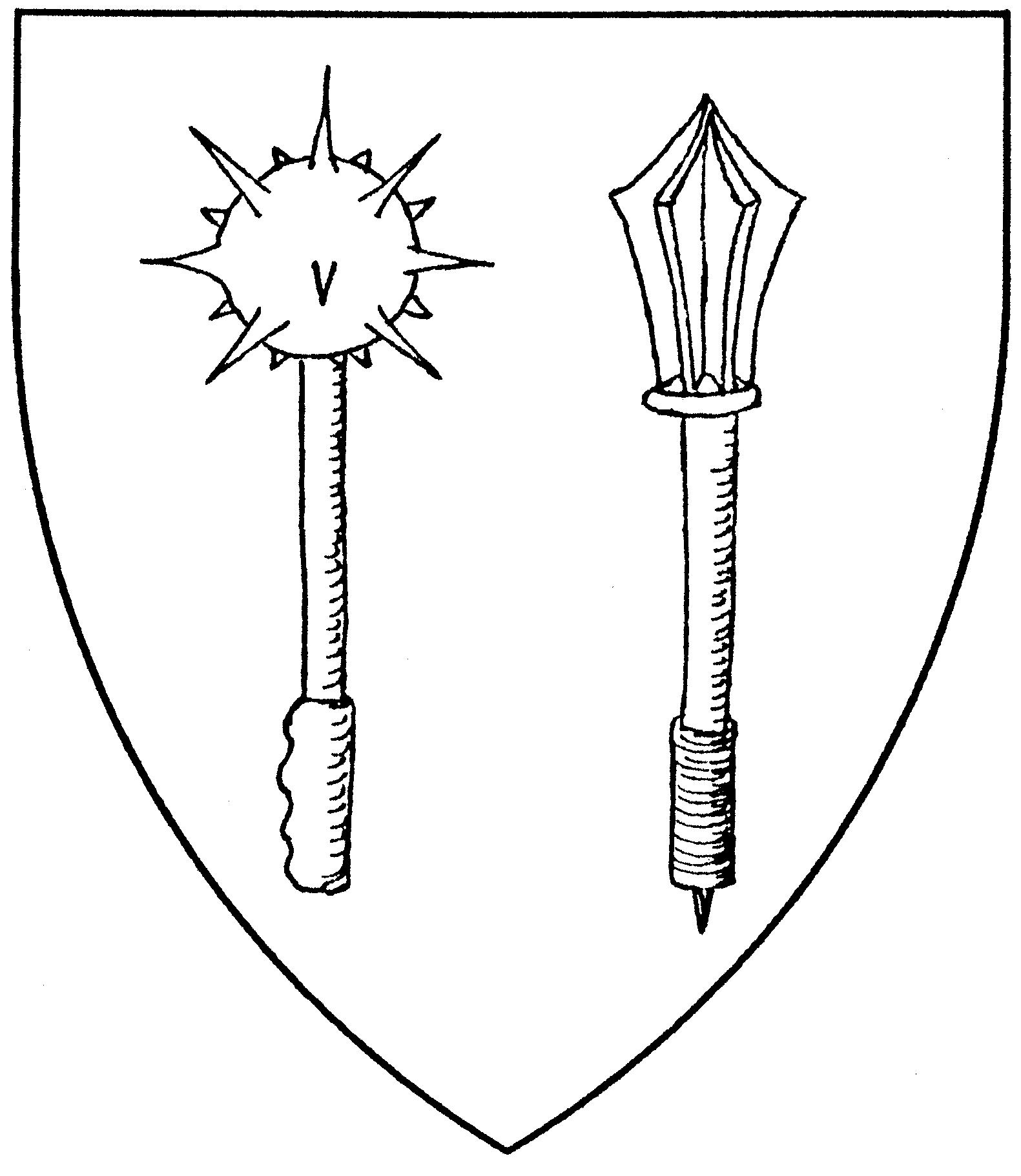

- The Middle Ages: This is the mace’s golden era. We started seeing "flanged" maces. These have blades or fins sticking out of the head. Why? To concentrate all that swinging force onto a tiny, sharp point. This actually allowed the mace to bite into or even puncture plate armor, rather than just denting it.

- The Pernach: In Eastern Europe and Russia, they developed a multi-flanged mace called a pernach. It was a terrifying piece of kit that doubled as a symbol of high military rank.

The "Holy" Weapon Myth

You've probably heard the story that priests and bishops used maces because they weren't allowed to "shed blood" with a sword. It’s a classic RPG trope. If you play Dungeons & Dragons, your Cleric is probably swinging a mace right now for this exact reason.

The truth is a lot messier.

While there is a famous depiction in the Bayeux Tapestry of Bishop Odo swinging a club-like object at the Battle of Hastings, most historians agree this "no blood" rule wasn't a universal law. Plenty of medieval clergy were perfectly happy to use swords when the situation called for it. Odo might have been using a mace because it was a symbol of authority, or simply because it was a more effective weapon against the armor of the day. The idea that maces don't shed blood is, frankly, hilarious to anyone who has seen what blunt force trauma does to a human face. It’s messy. It’s just a different kind of messy.

Why We Still See Maces Today (And Not Just in Museums)

You might think the mace died out when guns showed up. You'd be wrong.

📖 Related: Bondage and Being Tied Up: A Realistic Look at Safety, Psychology, and Why People Do It

During the horrific trench warfare of World War I, soldiers found themselves in cramped, muddy spaces where a long rifle with a bayonet was often too unwieldy. What did they do? They went back to basics. They started making "trench clubs," which were essentially improvised maces. They’d take a wooden handle, wrap it in barbed wire, or bolt metal studs into the top. It was a return to the primitive because, in a hole in the ground, a heavy thud is more reliable than a jammed pistol.

But there’s a more "civilized" version of the mace we see every year.

Ever watched a graduation ceremony or the opening of a parliament? That big, ornate gold stick being carried at the front of the procession? That’s a ceremonial mace. It represents the power and authority of the institution. In the U.S. House of Representatives, there is a "Mace of the House" that dates back to 1841. It’s made of silver and ebony. When the House is in session, the mace sits on a pedestal. If things get too rowdy, the Sergeant at Arms can actually pick it up and present it to restore order. It’s a direct descendant of the weapon that used to crack helmets on the battlefield.

The Modern Fitness Twist: Steel Maces

If you walk into a "hardcore" gym today, you might see people swinging what looks like a sledgehammer with a ball on the end. This is the Steel Mace, or "Gada."

This isn't a new fad. It actually dates back to ancient Persian and Indian physical culture. Pehlwani wrestlers in India have been using the Gada for centuries to build insane core strength and shoulder mobility. Because the weight is so far away from your hands (the "offset load"), your body has to work ten times harder to stabilize it.

It’s one of those rare instances where an ancient weapon has transitioned perfectly into a functional movement tool. Swinging a mace in a "360" or a "10-to-2" pattern forces your lats, shoulders, and obliques to fire in a way that a dumbbell just can't replicate. It turns out that the same physics that made the mace a nightmare for knights makes it a dream for someone trying to get a six-pack and bulletproof shoulders.

👉 See also: Blue Tabby Maine Coon: What Most People Get Wrong About This Striking Coat

Real Talk: Mace vs. Morning Star

People mix these up constantly. It’s a pet peeve for history nerds.

A mace is a solid, fixed object. The head is attached directly to the handle. A morning star is specifically a mace head with spikes. And a flail? That’s the thing with the chain. If there’s a chain involved, it is not a mace. Period.

Using a flail is actually incredibly dangerous for the person swinging it—one bad bounce off a shield and you’ve just knocked your own teeth out. The mace is much more disciplined. It gives you more control and more direct feedback.

What You Should Do Next

If you’re fascinated by the history, I highly recommend checking out the Wallace Collection in London (online or in person). They have some of the most beautiful flanged maces in existence. You can see the craftsmanship—it’s not just a "big stick," it’s a piece of engineering.

If you’re more interested in the fitness side, don't just go out and buy a 20lb steel mace. That is a one-way ticket to a torn rotator cuff.

- Start light: A 7lb or 10lb mace is plenty for a beginner. The leverage makes it feel much heavier than it is.

- Learn the "Front Pendulum": Before you try swinging it behind your head, get used to the weight moving in front of you.

- Find a coach: Look for "Steel Mace Flow" or "Vintage Strength" certifications. There's a lot of nuance to not hitting yourself in the shins.

Whether it’s a symbol of government power, a tool for a brutal workout, or a relic of a violent past, the mace is one of the few objects that has survived almost every era of human civilization. It’s simple. It’s effective. It doesn't need to be sharp to be dangerous. That's the enduring legacy of the mace.