It is the song everyone knows by heart, even if they aren't religious. You've heard it at funerals, at presidential inaugurations, and probably hummed it in the shower once or twice. But the lyrics to the song Amazing Grace weren't originally written to be a chart-topping anthem or a civil rights staple. Honestly, they were the desperate scribblings of a man who was, by his own admission, a total wreck.

John Newton was a slave trader. That’s the uncomfortable, jagged truth at the center of this melody. He wasn't just a casual participant in the 18th-century Atlantic slave trade; he was a captain. He was known for being particularly foul-mouthed and rebellious, a man who even his fellow sailors found difficult to tolerate. When he wrote about being a "wretch," he wasn't being poetic or hyperbolic for the sake of a catchy hook. He meant it. He was a man who had participated in the systemic dehumanization of thousands of people, and when he finally faced his own mortality during a violent storm at sea in 1748, the words started to form.

The original verses you probably don't know

Most of us only sing the first three or four verses. We stop at "was blind, but now I see" and call it a day. But Newton’s original poem, titled "Faith’s Review and Expectation," actually had six stanzas. It wasn’t even a song at first. It was a poem intended to accompany a sermon he gave on New Year’s Day in 1773 at St. Peter and St. Paul's Church in Olney, England.

The fourth verse, which often gets skipped in modern hymnals, dives into the reality of mortality. It says:

The Lord has promised good to me,

His word my hope secures;

He will my shield and portion be,

As long as life endures.

Then it goes into the fifth and sixth verses, which get even more intense about the "dissolving" of the world. It’s heavy stuff. Newton wasn't trying to write a feel-good tune. He was trying to explain the theological concept of "Grace"—the idea that you get something beautiful and life-saving even when you deserve the exact opposite.

👉 See also: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

Where did the music come from?

Here’s a fun fact: Newton didn't write the melody. For the first fifty years or so of its existence, the lyrics to the song Amazing Grace were sung to dozens of different tunes. It was basically a set of lyrics looking for a home. It wasn't until 1835 that an American composer named William Walker paired the words with a traditional tune called "New Britain."

That’s the version we know today.

"New Britain" is likely based on West African sorrow songs or Scottish folk melodies. It uses a pentatonic scale—that’s five notes—which is why it sounds so haunting and universal. It’s easy to sing because it doesn't require a massive vocal range, yet it carries this weight that makes it feel ancient.

Why it became a civil rights anthem

In the 1960s, the song took on a whole new life. It’s kind of wild when you think about it. A song written by a former slave trader became the backbone of the American Civil Rights Movement. But that's the power of the lyrics. They speak to liberation. They speak to the idea that no matter how deep the darkness, there is a "shining as the sun" moment waiting on the other side.

Mahalia Jackson, the Queen of Gospel, used to perform it with such raw emotion that it transformed from a church hymn into a political statement. She lengthened the notes. She added "blue notes." She made the song breathe. When she sang it, it wasn't just about John Newton’s soul; it was about the soul of a nation trying to find its way out of the "many dangers, toils, and snares" of systemic racism.

✨ Don't miss: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

Common misconceptions about the lyrics

People get a lot of things wrong about this song.

First, there's a popular myth that Newton wrote the song immediately after he quit the slave trade. That’s not true. He actually stayed in the business for a few years after his "conversion" experience during that storm. Change is slow. It took him a long time to fully realize the horror of what he had done. He didn't become a vocal abolitionist until much later in his life, eventually working alongside William Wilberforce to end the slave trade in Britain.

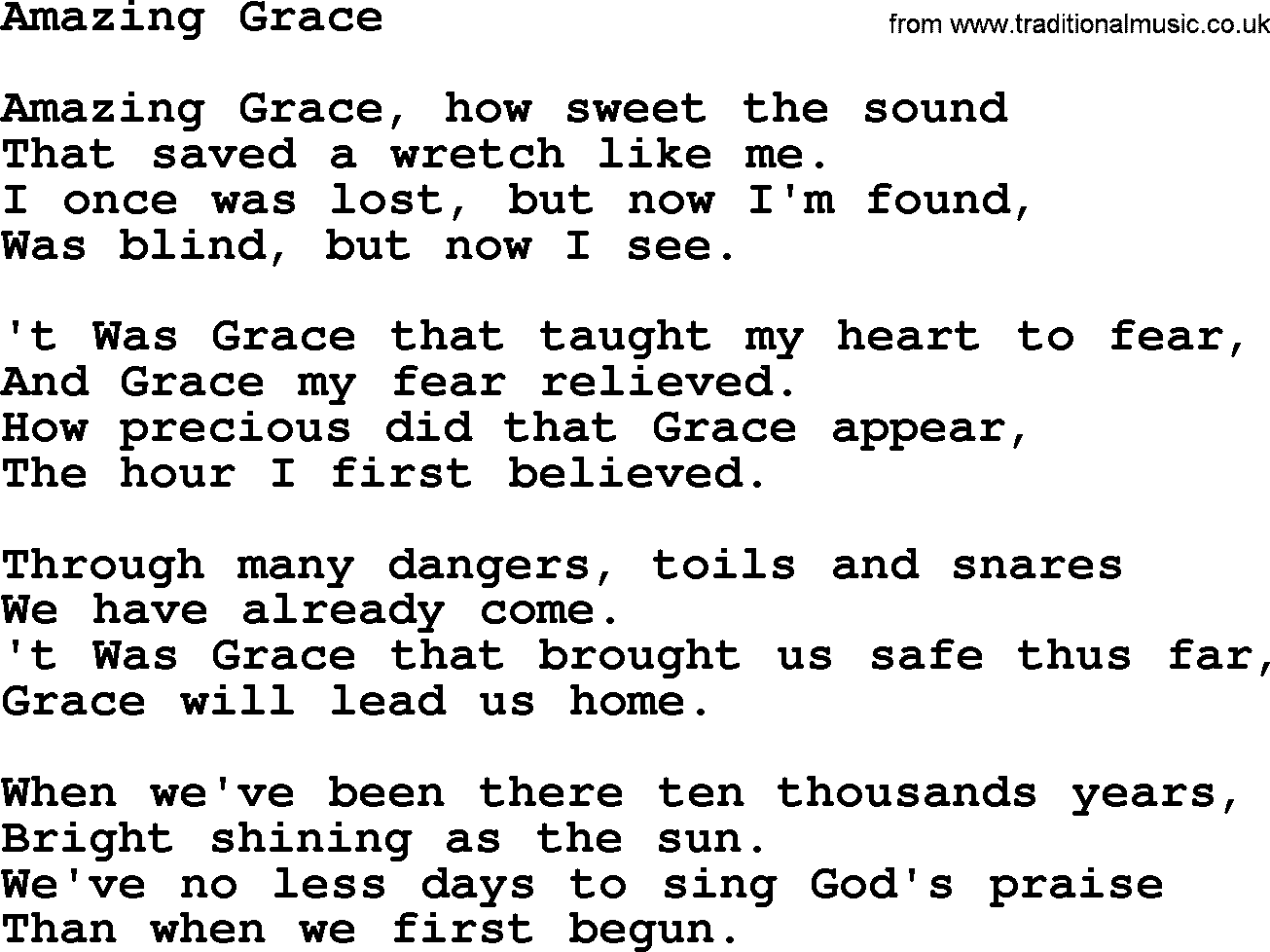

Another misconception is the "lost verse." You know the one: "When we've been there ten thousand years..."

Newton didn't write that.

That verse actually comes from a completely different song called "Jerusalem, My Happy Home." It was added to Amazing Grace in the late 19th century and popularized in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. It’s a great verse, but it’s basically 1800s fan fiction that became canon.

🔗 Read more: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

The technical side of the lyrics

If you look at the structure, it’s remarkably simple. Most lines are eight syllables followed by six syllables. This is called "common meter." It’s the same structure used in "Gilligan’s Island" or "The Yellow Rose of Texas."

- A-maz-ing grace! how sweet the sound (8)

- That saved a wretch like me! (6)

- I once was lost, but now am found, (8)

- Was blind, but now I see. (6)

This simplicity is why it’s so easy to memorize. It sticks in your brain. It feels like something you've always known.

But within that simplicity, there's a lot of nuance. Newton uses contrasts—lost and found, blind and see, grace and fear. It’s binary. It reflects the black-and-white nature of his life transition from a man who sold humans to a man who advocated for their freedom.

How to use these lyrics today

If you're looking to perform or study the lyrics to the song Amazing Grace, don't just stick to the standard four-verse version. Exploring the lesser-known stanzas can add a lot of depth to a performance.

- Try the fifth verse: "Yes, when this flesh and heart shall fail, / And mortal life shall cease; / I shall possess, within the veil, / A life of joy and peace." It adds a layer of vulnerability.

- Understand the tempo: Most modern versions are too slow. Historically, these hymns were often sung with a bit more of a rhythmic drive.

- Research the "Olney Hymns": This was the collection where Amazing Grace first appeared. Reading the other hymns Newton wrote with his friend William Cowper (a brilliant but troubled poet) gives you a much better sense of the mental space they were in.

There's something deeply human about the fact that our most beloved song was written by someone who had so much to apologize for. It suggests that if grace could find John Newton, it can probably find anyone. That’s why we still sing it. Not because it’s a pretty tune, but because it’s a survival manual set to music.

To truly appreciate the song, find a recording of the "Sacred Harp" or "Shape Note" singing style. This is how the song would have sounded in the rural South in the 1800s—loud, haunting, and without any instruments. It strips away the polished cathedral vibes and gets back to the raw, grit-teeth hope that the lyrics were meant to convey. Also, take a look at the John Newton Project online; they have digital copies of his original diaries which show the messy, unedited versions of his thoughts before they became the legendary lyrics we know today.