You’ve heard it. Even if you haven't stepped foot in a cathedral or a dusty country chapel in a decade, you know the swell of that chorus. It’s a literal powerhouse of a song. Most people think "How Great Thou Art" is some ancient relic from the 1700s, born alongside the works of Isaac Watts or Charles Wesley. Honestly? Not even close. The lyrics hymn how great thou art enthusiasts obsess over actually have a much weirder, more international passport than you’d expect. It’s a song that traveled from a lightning storm in Sweden to a mission in Ukraine before finally exploding in a Billy Graham crusade in New York.

It's massive.

The song doesn't just ask you to sing; it demands it. When that refrain kicks in—"Then sings my soul"—the acoustics of the room usually change. But to understand why these specific words resonate across cultures, you have to look at where they crawled out of. It wasn't a boardroom or a professional songwriting session. It was a moment of sheer, unadulterated terror and awe in the Swedish countryside.

The Thunderstorm That Started It All

Carl Boberg was a 23-year-old poet and lay minister. In 1885, he was walking home from church near Mönsterås, Sweden. Imagine the scene: the sky turns that weird bruised purple color, the wind starts whipping through the trees, and suddenly, a massive crack of thunder rattles his teeth. A summer storm caught him off guard. In Sweden, these storms can be violent and sudden. Boberg watched the rain drench the fields and then, just as quickly, the sun came out. The birds started singing in the woods. Church bells were ringing in the distance.

He didn't go home and write a "hit." He wrote a poem called "O Store Gud."

He published it in a local newspaper. It was just a Nine-stanza poem about the transition from the roar of nature to the quiet peace of God. He probably thought that was the end of it. It wasn’t. People started matching it to an old Swedish folk melody. It was catchy, but it was still stuck in Scandinavia.

Most people don't realize how much the lyrics hymn how great thou art changed as they moved across borders. The version we sing today isn't even a direct translation of Boberg's original poem. It’s a translation of a translation of a translation. It went from Swedish to German, then German to Russian.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Right Word That Starts With AJ for Games and Everyday Writing

Stuart Hine and the Ukrainian Connection

This is where the story gets really interesting. Enter Stuart Hine, an English missionary. In the 1930s, Hine and his wife were ministering in Ukraine (then part of the Soviet Union). They heard the Russian version of the song and were floored by it. But Hine didn't just translate the words; he lived them.

The first three verses he wrote were inspired by specific moments in the Carpathian Mountains. He saw the "lofty mountain grandeur" and heard the "rolling thunder" of the storms there. But the third verse? That one is heavy. It wasn't just about nature. It was about the people he met in Ukraine who were suffering under the weight of the era’s political turmoil, yet finding peace in their faith.

When Hine eventually returned to Britain, he added a fourth verse after World War II. He was thinking about the displaced persons and refugees who were longing for a home. That’s why the final verse feels so much like a sigh of relief. It’s about the end of the journey.

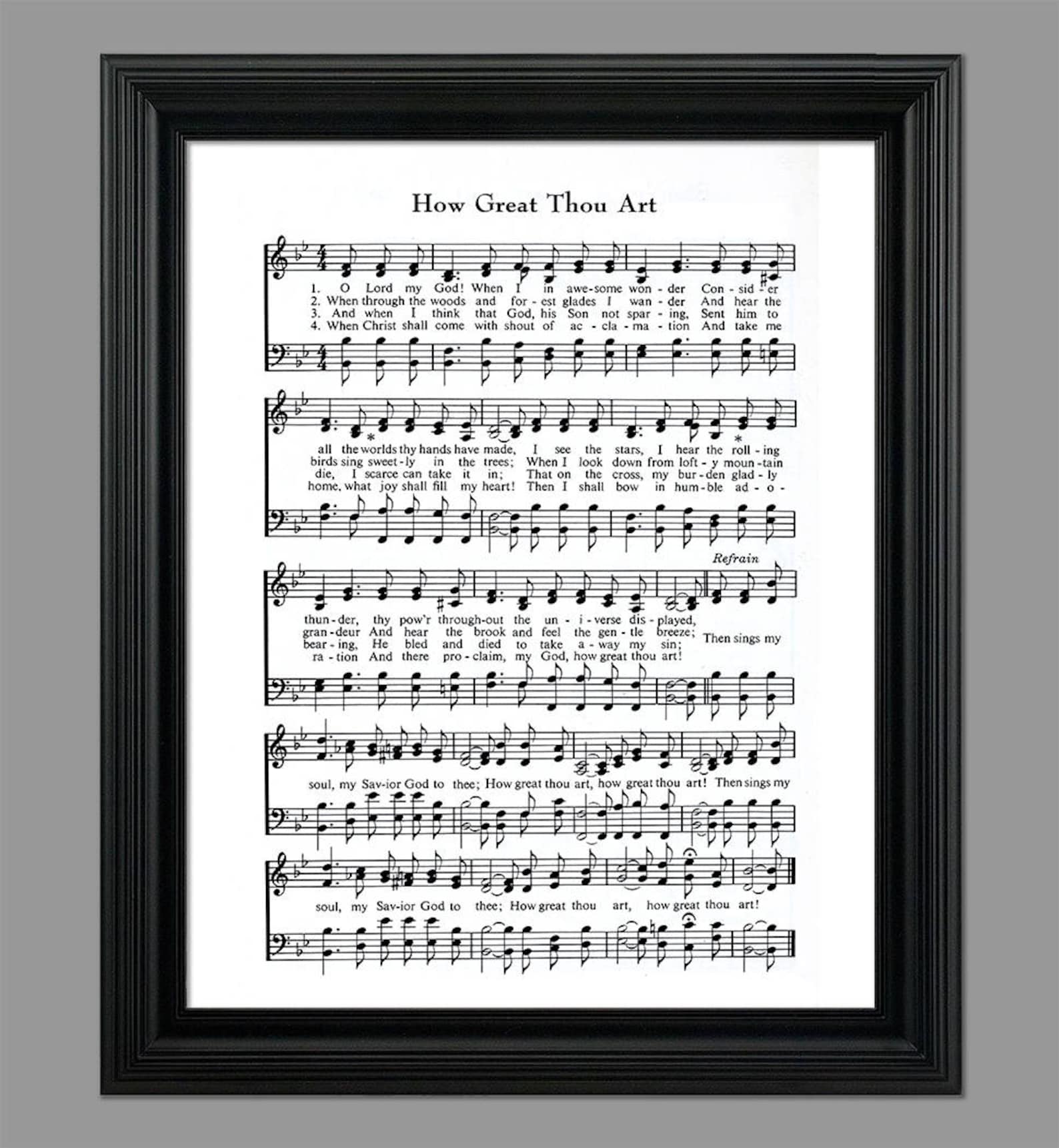

Breaking Down the Verse Structure

If you look closely at the lyrics hymn how great thou art, they follow a very specific emotional arc.

- The External World: "O Lord my God, when I in awesome wonder..." This is the macroscopic view. Stars, thunder, the universe. It’s the "look at the big picture" moment.

- The Natural World: "When through the woods and forest glades I wander..." This is the microscopic view. Birds, cool breezes, trees. It’s intimate.

- The Spiritual World: "And when I think that God, His Son not sparing..." This is where the theology kicks in. It’s the pivot from "Wow, look at the trees" to "Wow, look at the sacrifice."

- The Eternal World: "When Christ shall come with shout of acclamation..." This is the climax. It’s the future tense.

The brilliance of the song is the chorus. The refrain acts as a release valve. The verses build up this intellectual and emotional tension, and the chorus lets it all out. Then sings my soul. It’s a physical experience to sing those words.

Why This Song Became a Global Phenomenon

For decades, the hymn was popular in small circles, but it didn't become a "superstar" song until 1957. Billy Graham was holding his New York Crusade at Madison Square Garden. George Beverly Shea, a baritone with a voice like velvet and gravel, started singing it.

💡 You might also like: Is there actually a legal age to stay home alone? What parents need to know

The audience went nuts.

They had to sing it every night. They sang it 99 times during that one crusade alone. It was the "Free Bird" of the hymnal. People couldn't get enough of it. Why? Probably because the mid-20th century was a time of massive anxiety. The Cold War was ramping up, the world felt fragile, and here was a song that reasserted a sense of cosmic order.

It’s also incredibly versatile. You can sing it as a quiet, weeping ballad (think Carrie Underwood or Elvis Presley) or you can belt it out with a full pipe organ and a 200-person choir. It works both ways. Not many songs do. Elvis actually won a Grammy for his version in 1967. Think about that: a Swedish poem from 1885 won a Grammy in the era of The Beatles and Hendrix.

Nuance and Controversy: The Translation Trap

Is the version we sing "accurate"?

Purists sometimes complain that Stuart Hine took too many liberties. Boberg's original Swedish text is more of a meditation on the seasons and the cycle of life. Hine’s version is much more overtly evangelical and focused on the atonement. Some argue we lost the "nature poet" vibe of Boberg in favor of the "missionary zeal" of Hine.

Honestly, does it matter? In the world of hymns, the "folk process" is king. A song becomes what the people need it to be. The lyrics hymn how great thou art survived because they are adaptable. They survived the transition through four languages and multiple continents because the core sentiment—"I am small, the universe is big, and there is a power behind it all"—is universal.

📖 Related: The Long Haired Russian Cat Explained: Why the Siberian is Basically a Living Legend

Actionable Insights for Using the Hymn Today

If you’re looking to incorporate this hymn into a service, a performance, or just a personal study, there are a few ways to make it more impactful than just "singing the hits."

- Vary the Dynamics: Don't start at a level 10. The first verse should be a whisper. If you blast the first verse, you have nowhere to go when the fourth verse hits. Build the volume incrementally.

- Contextualize the "Woods": When you sing the second verse, think of a specific place you've been. For Boberg, it was the Swedish coast. For Hine, it was the Carpathians. For you, it might be a local park or a backyard. Grounding the lyrics in real geography makes them less abstract.

- Acknowledge the Third Verse: Many modern "radio" versions skip the third verse about the cross. Don't. It’s the bridge between the beauty of nature and the reality of the human condition. Without it, the song is just a nature poem.

- Check the Tempo: Most people drag this song like a funeral march. It’s not. It’s a song of "awesome wonder." Pick up the pace slightly. Let it breathe.

The lyrics hymn how great thou art are more than just words on a page or a screen. They are a historical map of human experience, spanning from the 19th-century Swedish countryside to the front lines of 20th-century missions. They remind us that even in a world that feels increasingly digital and disconnected, the roar of a thunderstorm and the quiet of a forest still have the power to make our "souls sing."

If you want to truly appreciate the depth here, try reading Boberg’s original nine verses (translated literally). You’ll see a much wider scope of nature, including mentions of "thick clouds" and "fertile meadows" that didn't make the English cut. It gives you a much broader appreciation for the man who stood in the rain and decided that instead of running for cover, he would write a poem.

To dig deeper into the actual performance of the piece, listen to the 1957 live recording of George Beverly Shea. You can hear the crackle of the audio and the sheer scale of the crowd. It’s the closest you’ll get to understanding how a humble poem became the world's most recognizable anthem of praise. Or, if you prefer a more modern take, look for the version by the Brooklyn Tabernacle Choir. It shows the song’s ability to handle massive, complex harmonies without losing its heart.

The next step is simple: next time you hear it, don't just listen to the melody. Look at the transition from the "rolling thunder" to the "gentle breeze." That’s the real magic of the song—it finds God in both the chaos and the quiet.