It starts with a taxi meter. That clicking, mechanical sound is the only thing grounding Frank Ocean as he pours his soul out to a driver who doesn't speak his language. Or maybe he does. It doesn't actually matter because the lyrics bad religion frank ocean fans have obsessed over since Channel Orange dropped in 2012 aren't really about a conversation. They're about a confession.

He’s in the backseat. He’s desperate. He’s asking a stranger to be his therapist because the weight of unrequited love for another man is crushing him.

Frank didn't just write a song about a crush. He wrote a song about the agony of devotion to something—or someone—that cannot love you back. It’s a "bad religion." It’s a one-man cult. Honestly, if you’ve ever sat in the back of an Uber at 3:00 AM feeling like your chest is hollow, you’ve lived this song.

The Taxi Driver as a Secular Priest

The setup is genius. By choosing a taxi driver as the listener, Frank creates a temporary, anonymous sanctuary. He tells the driver to "keep the meter running," which is basically him paying for a confession. He needs a witness.

The opening lines are iconic: "Taxi driver, be my shrink for the hour."

It’s blunt. It’s vulnerable.

Most people focus on the religious metaphors, but the real power lies in the power dynamic. Frank is the passenger, but he’s also a prisoner of his own feelings. He’s "cyanide in my Styrofoam cup." That’s a heavy reference to the Jonestown Massacre. He’s literally saying that loving this person is a form of spiritual suicide. He knows it's killing him, but he’s still drinking the Kool-Aid.

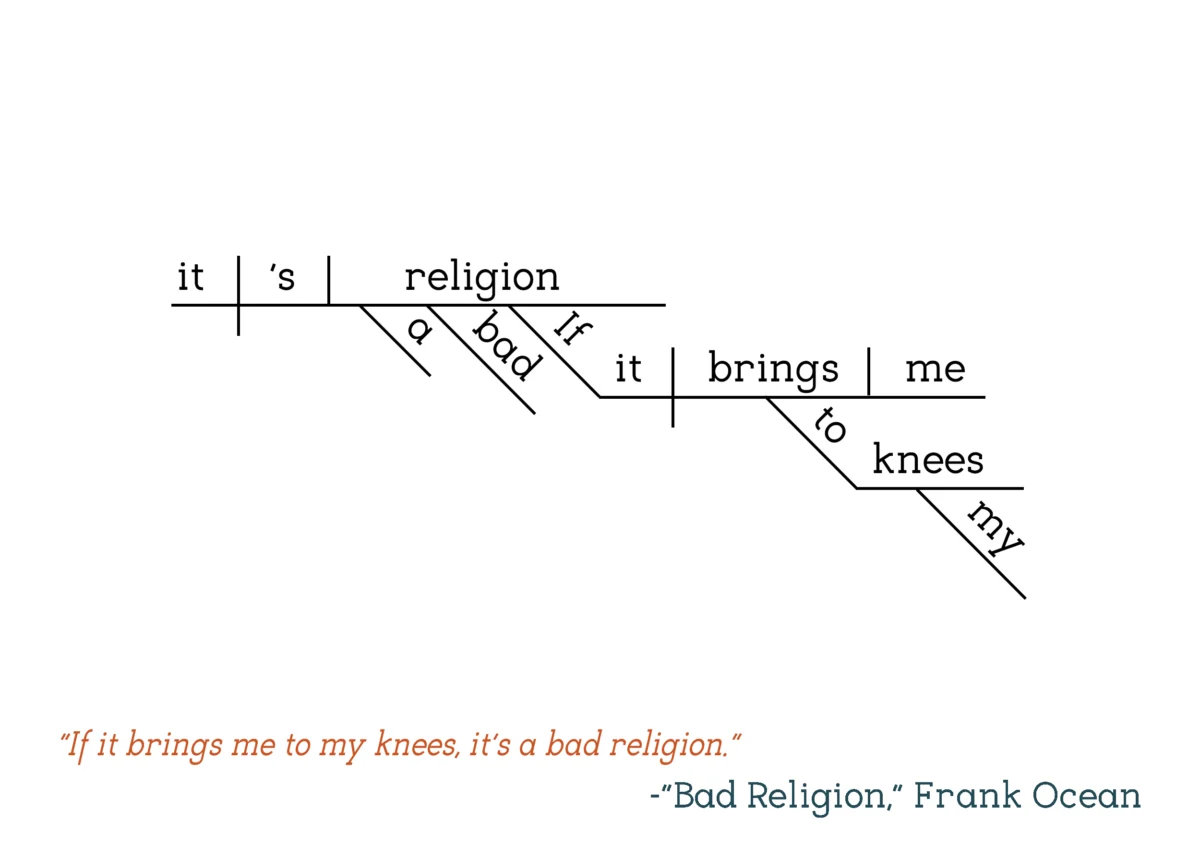

The driver responds with "Allahu Akbar," and Frank’s reaction is where the song gets its title. He says, "If it brings me to my knees, it’s a bad religion." He isn't attacking Islam or any specific faith. He’s making a profound psychological point: anything that demands your total submission but offers no salvation in return is a "bad religion."

📖 Related: Big Brother 27 Morgan: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

Why the "Unrequited" Narrative Changed Everything

You have to remember the context of 2012.

Before Channel Orange was released, Frank posted an open letter on Tumblr. It was a bombshell. He talked about his first love being a man. In the hyper-masculine world of R&B and hip-hop at the time, this was revolutionary. It wasn't just a PR move; it was a soul-baring moment that gave the lyrics bad religion frank ocean wrote a devastating layer of reality.

When he sings about a "three-man army" or the idea that he can never make this person love him, he isn't just being poetic. He’s talking about the wall of heteronormativity. He’s talking about a love that, in his mind at the time, was fundamentally impossible.

It’s painful.

The song doesn't have a bridge that leads to a happy ending. There is no resolution. The strings, arranged by the legendary Malay and Om'Mas Keith, swell into this massive, orchestral climax that feels like a breakdown. And then? It just ends. The meter is still running. The bill is still due.

Debunking the Controversy: Is it Anti-Religious?

Over the years, people have tried to claim the song is Islamophobic or anti-theistic. That’s a shallow read.

Frank uses the "Allahu Akbar" (God is Great) line as a foil. The driver is offering a path to something greater, a traditional faith. Frank’s response—"If it brings me to my knees, it’s a bad religion"—is a commentary on his own obsession. He is comparing his unrequited love to a dogmatic faith.

👉 See also: The Lil Wayne Tracklist for Tha Carter 3: What Most People Get Wrong

Think about it:

- Faith requires belief without proof.

- Unrequited love requires devotion without reciprocation.

- Both involve "kneeling" or humbling yourself before something you can't control.

He’s saying that his love is a cult of one. He’s the only member, and the deity he’s worshipping doesn't even know he’s there. That’s not a critique of the driver’s faith; it’s a self-indictment of Frank’s own emotional state. It's actually quite humble. He’s admitting he’s broken.

The Sonic Architecture of a Breakdown

The music itself tells half the story. The organ. Oh man, that organ.

It sounds like it belongs in a cathedral, but it’s trapped in a soul record. It creates this eerie, sanctified atmosphere that contrasts with the grit of a dusty taxi cab. When Frank hits those high notes—specifically on the word "love" in the chorus—you can hear his voice almost crack.

It’s not "perfect" singing. It’s emotional singing.

Music critics like Pitchfork’s Ian Cohen noted at the time that the song anchored the emotional arc of the album. It’s the moment where the bravado of tracks like "Pyramids" or the nostalgia of "Sweet Life" falls away. We are left with just Christopher Breaux (Frank's birth name) and his grief.

Interestingly, the song is quite short. It’s under three minutes. In that time, he manages to deconstruct the entire concept of romantic devotion. Most songwriters need an entire concept album to do what Frank did in one verse and two choruses.

✨ Don't miss: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

Real-World Impact and Legacy

The lyrics bad religion frank ocean penned have become a sort of anthem for the "invisible" lover.

I’ve seen this song discussed in therapy groups and music theory classes alike. Why? Because it touches on the specific "dark" side of love that we usually don't talk about. We like songs about winning love or even songs about breaking up. We don't usually like songs about the pathetic, crawling feeling of wanting someone who will never want us back.

It’s embarrassing to feel that way. Frank makes it art.

In the decade-plus since its release, the song has been covered by everyone from Amber Riley (Glee) to various indie bands. But nobody quite captures the "locked-in-a-box" feeling of the original. There’s a specific loneliness in Frank’s delivery that can’t be replicated.

Actionable Takeaways for Listeners

If you’re dissecting these lyrics for a project or just because you’re in your feelings, here is how to actually engage with the track's depth:

- Listen for the Meter: Notice the clicking sound at the beginning and end. It symbolizes that his time—and his money—is running out. His catharsis is temporary.

- Analyze the "Pink Matter" Connection: Frank often uses colors to describe emotions. In "Bad Religion," the palette is dark, shadows and "cyanide." Contrast this with the later tracks on the album to see his emotional progression.

- Observe the "Double Meaning" of Kneeling: In a religious context, kneeling is for worship. In a romantic context, it can be for a proposal or for begging. Frank is doing the latter, and he hates himself for it.

- Read the Tumblr Letter: To truly "get" the song, you have to read Frank’s 2012 open letter. It provides the "who" and the "why" that makes the lyrics feel less like a story and more like a diary entry.

Ultimately, "Bad Religion" isn't a song you listen to when you're happy. It's a song you listen to when you need to know that someone else has felt just as small as you do. It’s a masterpiece of vulnerability. It reminds us that sometimes, the most "religious" thing we can do is admit we are completely and utterly lost.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Understanding:

Go back and listen to the transition between "Monks" and "Bad Religion." The shift from the chaotic energy of the crowd to the quiet isolation of the taxi is intentional. It highlights the "comedown" from a public life to a private heartbreak. Study the use of the "three-man army" metaphor—it’s a reference to the complexity of a love triangle where one person is essentially fighting a ghost.