If you want to understand the exact moment post-punk died and something much more colorful was born, you have to talk about the Low-Life New Order album. It’s 1985. The gloom of Joy Division is a fading shadow, though it never quite disappears. Bernard Sumner, Peter Hook, Stephen Morris, and Gillian Gilbert finally stopped apologizing for surviving. They went to the Bahamas to record some of it, but they brought the grey Manchester rain in their suitcases.

The result was something weird. It was confident.

Honestly, most people point to Power, Corruption & Lies as the definitive New Order statement. I get it. "Age of Consent" is a perfect song. But Low-Life is where the band stopped being a "project" and became a definitive, world-conquering force. It’s the record where the synthesizers and the guitars finally stopped fighting and started dancing. You can hear it in the opening thrum of "Love Vigilantes." It’s a trick, really. It sounds like a jaunty folk-rock tune, but the lyrics are a devastating gut-punch about a soldier returning home as a ghost. Typical New Order. They make you dance while your heart breaks.

The Peter Hook Bassline That Defined a Decade

You can’t talk about the Low-Life New Order album without mentioning Peter Hook’s thumb. On this record, the bass isn't just a rhythm instrument. It's the lead guitar. On "The Perfect Kiss," Hooky plays so high up the neck it sounds like a cello. It’s melodic. It’s aggressive. It’s kind of the soul of the whole operation.

There’s a legendary story about the recording of "The Perfect Kiss." They kept adding layers. Cowbells. Frog samples. Massive, sweeping synth pads. It shouldn't work. It should be a cluttered mess. Yet, in the hands of producer Michael Johnson and the band, it became a nine-minute epic on the 12-inch version that basically blueprinted the next twenty years of electronic music.

Stephen Morris is the secret weapon here. People forget he’s a human drum machine. On Low-Life, he’s blending live kits with the E-mu Drumulator in a way that feels seamless. It’s not stiff. It’s got this nervous, driving energy that keeps the tracks from feeling too "studio-produced."

💡 You might also like: Not the Nine O'Clock News: Why the Satirical Giant Still Matters

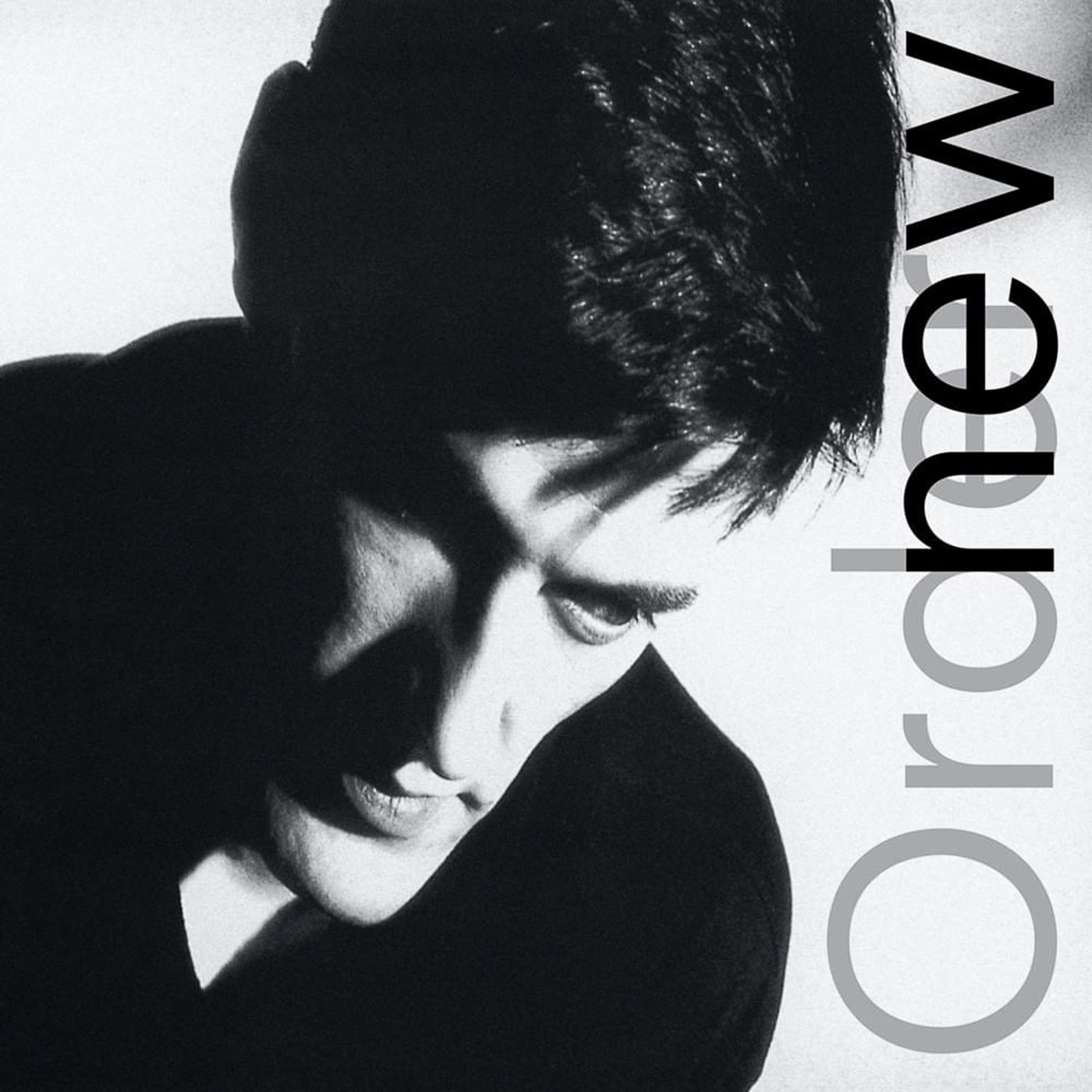

Why the Cover Art Mattered

Peter Saville, the legendary Factory Records designer, did something different for this one. Usually, New Order covers were mysterious. No band photos. No names. Just flowers or abstract shapes. For the Low-Life New Order album, he put Stephen Morris on the front. Just a blurry, black-and-white photo of a band member.

It was a statement of identity.

They were no longer the "remains of Joy Division." They were people. They had faces. The inner sleeve featured the other members—Bernard looking boyish, Gillian looking coolly detached, and Hooky looking like a pirate. It felt intimate. It felt like they were finally letting the audience in on the joke, or at least letting them see the people behind the machines.

The Weird Duality of Sunrise and Elegia

The middle of the album is where things get heavy. "Sunrise" is arguably the loudest, most aggressive track New Order ever put to tape. It’s a storm. Bernard’s guitar is jagged and distorted, slashing through the mix. If you ever hear someone say New Order was "just a synth band," play them "Sunrise" at maximum volume. It’ll change their mind real fast.

Then you have "Elegia."

📖 Related: New Movies in Theatre: What Most People Get Wrong About This Month's Picks

It’s an instrumental. It’s five minutes of pure, cinematic mourning. They wrote it for Ian Curtis, five years after his death. It feels like a long-delayed exhale. While the rest of the Low-Life New Order album is busy inventing the future of club music, "Elegia" stays rooted in that cold, cavernous feeling of the past. It’s beautiful. It’s also incredibly lonely.

Interestingly, the full version of "Elegia" is actually seventeen minutes long. They had to cut it down for the vinyl because, well, physics. But even in its shorter form, it’s the emotional anchor of the record. It gives the album a weight that "Blue Monday" or "Confusion" didn't necessarily have.

The Production Secrets of 1985

- The Gear: They were using the Sequential Circuits Prophet-5 and the Emulator II. These were the Ferraris of the synth world back then.

- The Studio: Much of it was done at Jam Studios in London.

- The Vibe: It was chaotic. The band was notorious for spending massive amounts of money on studio time just to hang out or experiment with one specific snare sound for twelve hours.

Basically, they were refining the "Manchester Sound." It’s that mix of industrial grit and high-gloss pop. You can hear the influence of the New York club scene—places like the Fun House or the Danceteria—bleeding into the tracks. They were taking what they learned from Arthur Baker and bringing it back to a rainy studio in England.

The Lyricism of Bernard Sumner

Let's be real: Bernard Sumner isn't Leonard Cohen. His lyrics can be... simple. Sometimes they're even a bit clunky. But on the Low-Life New Order album, that simplicity is his greatest strength.

"Sub-culture" is a great example. "One of these days my sky will fall / I'll lose my mind and lose it all." It’s direct. It’s the kind of stuff you scream in a basement club when you're twenty-two and the world feels too big. He captures a specific kind of urban anxiety. He doesn't use big metaphors. He just tells you he's tired or he's lonely or he's in love.

👉 See also: A Simple Favor Blake Lively: Why Emily Nelson Is Still the Ultimate Screen Mystery

There's a vulnerability there that a more "poetic" writer might have ruined.

Does it still hold up?

Absolutely. If you listen to modern bands like The Killers, M83, or Cut Copy, you can hear the DNA of Low-Life everywhere. That specific blend of melancholic melody and danceable rhythm is the foundation of modern indie-electronic music.

Some people complain about the "Sub-culture" remix on the album, saying it's too polished compared to the rest. I disagree. I think it shows the band's ambition. They weren't content staying in the "indie" ghetto. They wanted the charts. They wanted the dancefloor. They wanted everything.

How to Experience Low-Life Today

If you’re just getting into this record, don't just stream it on crappy earbuds while you’re on the bus. You need to hear the dynamic range.

- Find the 2023 Definitive Edition. The remastering is actually good. It doesn't squash the sound; it just breathes a bit more life into the low end.

- Listen to "The Perfect Kiss" (Full Version). The album version is great, but the 12-inch version with the extended percussion break and the frog synths is a religious experience.

- Watch the "Live at the Hacienda" footage from '85. You’ll see a band that is both incredibly tight and seemingly about to fall apart at any second. It’s electric.

The Low-Life New Order album is more than just a collection of songs. It’s a document of a band figuring out how to be a band again. They moved past the tragedy of Joy Division not by forgetting it, but by building something shiny and new on top of the ruins. It’s messy, it’s brilliant, and it’s arguably the most "human" electronic record of the 1980s.

To really appreciate it, you have to look at the tracklist as a journey. You start with the fake-out of "Love Vigilantes," trek through the darkness of "Elegia" and "Sunrise," and end with the defiant pop of "Face Up." By the time Bernard yells "Oh, I cannot explain!" at the end of the record, you realize he doesn't have to. The music already did.

Next Steps for the Listener:

- Compare the production: Listen to Power, Corruption & Lies and then Low-Life back-to-back. Notice how the drums become more prominent and the synth textures become more "layered."

- Track the 12-inch singles: New Order was a singles band as much as an album band. Seek out the B-sides from this era, like "The Shellshock," to see how they were pushing the boundaries of dance music.

- Explore the Saville aesthetic: Look up the original vinyl inserts. The typography and the choice of paper stock were all part of the "Low-Life" experience, intended to make the physical object feel like a piece of art.