Peter Brook didn’t want professional actors. He didn't want a polished script or a safe, predictable Hollywood set. Honestly, that’s why the Lord of the Flies movie 1963 feels less like a piece of cinema and more like a found-footage nightmare from a decade that didn't even have a name for that genre yet.

It’s raw.

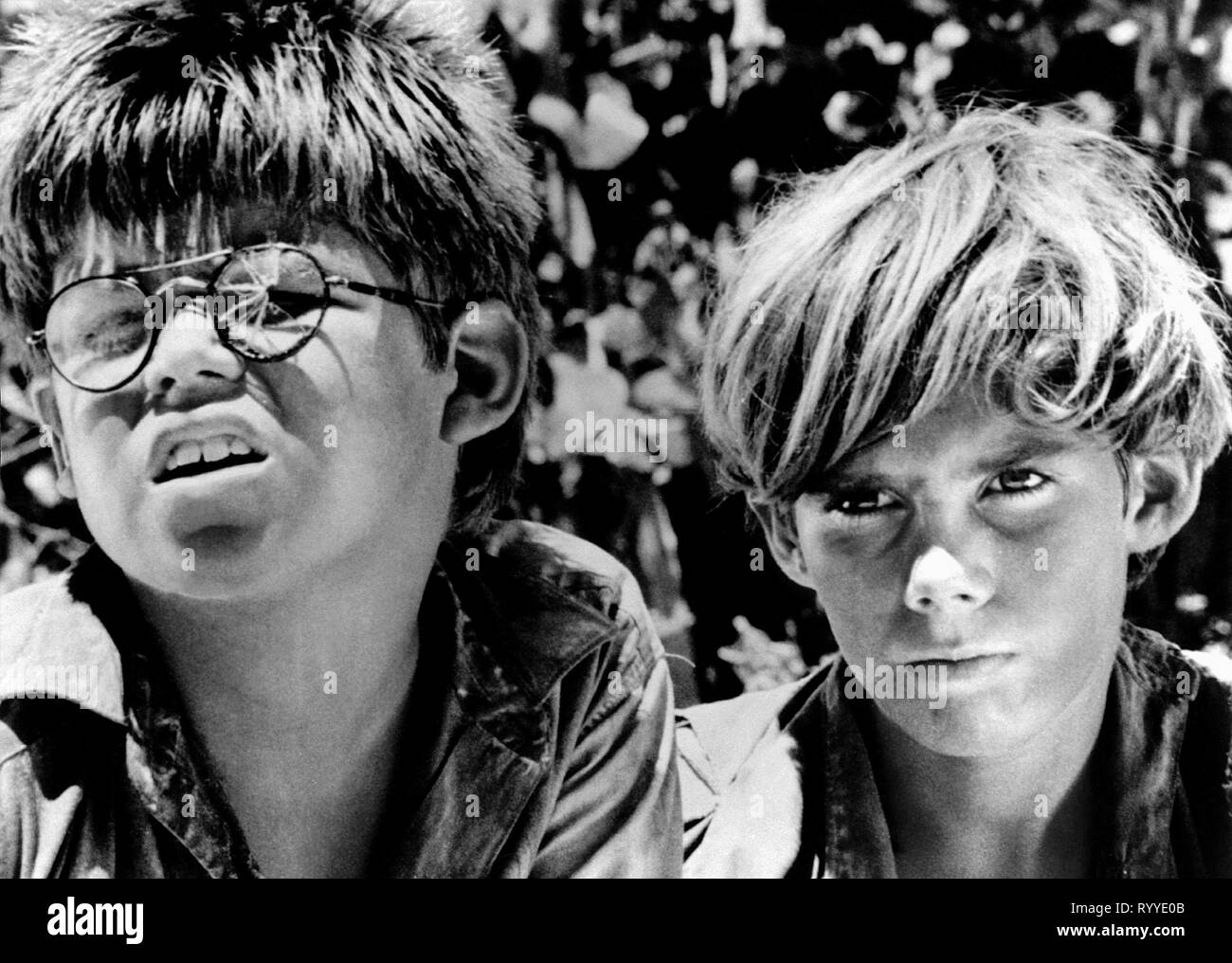

If you watch it today, the grainy black-and-white film stock makes the tropical setting look skeletal and harsh, which is exactly how William Golding’s 1954 novel was meant to feel. Most directors try to "interpret" a book. Brook just let it happen. He took 30 non-actor schoolboys to the island of Vieques off Puerto Rico, threw away the traditional screenplay, and basically filmed a descent into madness.

The result? A film that remains vastly superior to the 1990 technicolor remake. While the later version felt like a bunch of kids playing dress-up, the 1963 original feels like you're watching actual societal collapse in real-time. It’s haunting.

The Chaos Behind the Lord of the Flies Movie 1963

Most people don't realize how unscripted this thing actually was. Brook was a theater director by trade, and he had this radical idea that if you wanted to capture the "natural" behavior of children, you couldn't give them lines to memorize. He shot over 60 hours of footage. That's a ridiculous ratio for a 90-minute movie.

He used a technique where he would describe a situation to the boys—say, "you’re hungry and you’re starting to hate Ralph"—and then he’d just let the cameras roll. Sometimes he’d use a tape recorder to capture their natural banter and then dub it back in later to keep that authentic, unpolished cadence of mid-century British schoolboys.

You can see it in their eyes. James Aubrey, who played Ralph, has this look of genuine, mounting exhaustion as the film progresses. It wasn't just acting. The production was grueling. They were living in an abandoned pineapple cannery. The heat was oppressive.

Why Black and White Matters Here

You might think color would make a deserted island look more "real." You’d be wrong.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Cast of Hold Your Breath 2024 Makes This Dust Bowl Horror Actually Work

By stripping away the lush greens and blues of the Caribbean, Brook forced the audience to focus on the textures: the grit of the sand, the sweat on a dirty forehead, and the terrifying starkness of the pig’s head on a stick. It turns the island into a psychological space rather than a vacation spot gone wrong. It becomes a void.

In the Lord of the Flies movie 1963, the shadows are deep and jagged. When Jack’s choir-turned-hunters emerge from the brush with their faces painted, the high-contrast film makes them look like ancient statues or demons. It’s a visual trick that color film, with its distracting vibrance, usually fails to pull off.

The Sound of Civilization Breaking

The score is sparse. It’s mostly just the sound of a lone fife or the rhythmic, tribal drumming that starts to take over the soundtrack as the boys lose their grip on reality.

There’s a specific scene where the conch—the symbol of order and "talking turns"—is smashed. In the book, it's a huge moment. In the 1963 film, the sound of it shattering is followed by a silence that feels heavy. It’s one of those moments where you realize the "rules" are gone.

Tom Gaman, who played Simon, gives a performance that is legitimately eerie. Simon is the "Christ figure" of the story, the one who realizes the "Beast" isn't a physical monster but something inside the boys. Brook captures Simon’s hallucination with the Lord of the Flies (the fly-infested pig head) using quick cuts and a dizzying camera style that felt years ahead of its time.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Ending

People often complain that the ending is too abrupt. The naval officer shows up, the boys stop crying, and the credits roll. But that’s the whole point.

The officer looks at the filth-covered, murderous children and scolds them for not putting up a "better show" of British decency. The irony is thick enough to choke on. He’s a soldier in the middle of a global nuclear war—the film is set against the backdrop of an atomic conflict—yet he’s judging children for the very violence he’s currently engaged in on a much larger scale.

🔗 Read more: Is Steven Weber Leaving Chicago Med? What Really Happened With Dean Archer

The Lord of the Flies movie 1963 captures this hypocrisy better than any other adaptation. It doesn't give you a "happy" rescue. It shows you that the boys are just being brought back to a "civilized" world that is doing exactly what they did, just with bigger bombs.

Real-World Nuance: Was Golding Right?

It’s worth noting that real-life "Lord of the Flies" scenarios haven't always ended in murder. In 1965, six boys from Tonga ended up shipwrecked on the island of 'Ata for 15 months. They didn't turn into savages; they built a garden, set up a permanent fire, and even managed to set a broken leg for one of their friends using sticks.

Does that make the 1963 movie a lie?

Not necessarily. Golding wasn't writing a sociology textbook. He was writing a response to his experiences in World War II, having seen what "good" people were capable of doing to one another when the veneer of society was stripped away. The film is a fable. It’s a "what if" scenario that explores the darkest corners of the human psyche. Brook’s direction treats the story with the gravity of a documentary, which is why it sticks in your ribs long after you finish it.

The kids in the 1963 film weren't actors being told to be mean. They were kids being allowed to be chaotic. That's a huge difference.

Key Elements That Define the 1963 Version

- The Casting: 3,000 boys were interviewed. Brook looked for kids who naturally fit the temperaments of the characters. He didn't want "theater kids."

- The Dialogue: Much of it was improvised or pulled directly from the book on the fly. This avoids the "stilted" feeling of many 60s films.

- The Cinematography: Gerald Feil used handheld cameras in ways that were revolutionary for the time. It gives the hunt scenes a frantic, claustrophobic energy.

- The Pig: The "Lord of the Flies" itself was a real, decaying pig's head. The actors’ reactions to the smell and the flies were entirely genuine.

Watching It Today

If you're going to sit down and watch the Lord of the Flies movie 1963, don't expect a modern blockbuster pace. It’s deliberate. It’s slow-burn horror.

You have to look past the occasional "jolly good" and "right-o" and see the desperation underneath. By the time Piggy meets his end, the movie has shifted from a survival adventure into a full-blown tragedy. The lack of music in the death scenes makes them feel much more violent than they actually appear on screen.

💡 You might also like: Is Heroes and Villains Legit? What You Need to Know Before Buying

It remains a masterclass in independent filmmaking. It was shot on a shoestring budget with a cast of children who had never seen a camera, yet it’s more impactful than most $100 million thrillers.

Actionable Next Steps for Fans

To truly appreciate the depth of this adaptation, don't just stop at the credits. There are a few things you can do to get the full "Lord of the Flies" experience.

First, track down the Criterion Collection release. It includes an amazing commentary track with Peter Brook, producer Lewis Allen, and director of photography Gerald Feil. Hearing them describe the logistical nightmare of filming on a remote beach with 30 kids is almost as entertaining as the movie itself.

Second, compare it to the 1990 version. Specifically, look at the "conch" scenes. Notice how the 1963 version uses silence and framing to build tension, whereas the 1990 version relies more on music and traditional "action" editing.

Finally, read William Golding’s essay "Fable," where he explains why he wrote the book. It provides the necessary context for the film’s ending and why the naval officer's appearance is meant to be a moment of horror, not relief.

The 1963 film isn't just a movie; it's a warning. It’s a look at what happens when the lights go out and the adults aren't watching. It’s messy, it’s cruel, and it’s undeniably brilliant.