Ever get that weird, restless feeling in late June when the sun just refuses to quit? You’re sitting on the porch at 9:00 PM, and it’s still light enough to read a book without flicking a switch. That’s the summer solstice. Most people just call it the longest day of the year, but there is a whole lot of weird physics and historical baggage behind those extra hours of Vitamin D that usually gets left out of the conversation.

Honestly, the name is a bit of a lie.

Every single day on Earth is roughly 24 hours long because that’s how long it takes the planet to spin once on its axis. When we talk about the longest day, we’re really talking about the most daylight. In the Northern Hemisphere, this happens when the North Pole is tilted at its maximum toward the sun. It’s the peak of the cosmic swing. If you’re in the Northern Hemisphere, you’re looking at June 20, 21, or 22. In 2026, for example, the solstice officially hits on June 21st.

The Tilt That Changes Everything

Everything comes down to a 23.5-degree lean.

If the Earth sat perfectly upright, we wouldn't have seasons. We wouldn't have the solstice. Life would be incredibly predictable and, frankly, a bit boring. But billions of years ago, something massive—likely a protoplanet the size of Mars—slammed into Earth. It knocked us sideways. That tilt is why, for one day in June, the sun traces its highest and longest path across the sky.

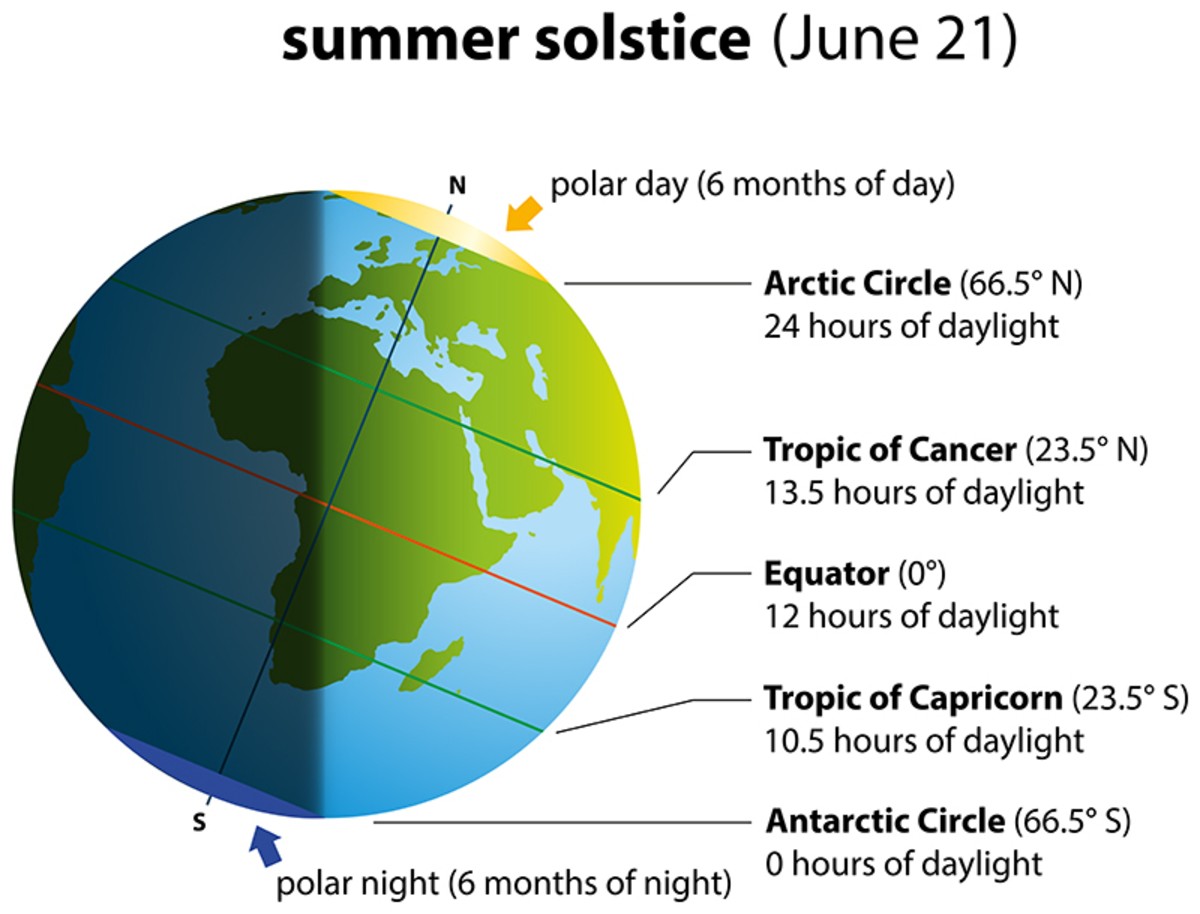

Think of it like a flashlight shining on a basketball. If you tilt the ball toward the light, the "North Pole" stays in the light even as you spin the ball. That’s why if you go far enough north, like Fairbanks, Alaska, or Tromsø, Norway, the sun doesn't actually set. They get 24 hours of light. It’s called the Midnight Sun, and it can seriously mess with your circadian rhythm.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Solstice

There is a massive misconception that the longest day of the year is also the hottest day of the year. It makes sense on paper, right? More sun should equal more heat.

Except it doesn't.

Meteorologists call this "seasonal lag." Think about a pot of water on a stove. Even when you turn the burner to high, it takes a while for the water to actually boil. The Earth is mostly covered in oceans, and water takes a long time to warm up. Even though we get the most solar radiation in June, the atmosphere and the seas don't reach their peak temperatures until late July or August. So, while June 21st gives you the most time to be outside, you’re usually sweating way more a month later.

💡 You might also like: December 12 Birthdays: What the Sagittarius-Capricorn Cusp Really Means for Success

Another thing: the earliest sunrise doesn't happen on the solstice.

Neither does the latest sunset. Because of the Earth's elliptical orbit and the way our clocks are built on averages rather than the actual "solar noon," the earliest sunrise usually happens about a week before the solstice. The latest sunset happens a week after. The solstice is just the point where the total duration of daylight reaches its maximum. It’s the mathematical peak, not the chronological bookend.

Stonehenge and the Human Obsession with Light

Humans have been obsessed with the longest day of the year for as long as we’ve been able to look up. It wasn't just about knowing when to plant crops; it was about survival and spirituality.

Take Stonehenge. If you stand in the center of that massive stone circle on the morning of the summer solstice, the sun rises directly over the Heel Stone. It’s a precision clock built out of multi-ton rocks. Thousands of people still flock to Salisbury Plain every year to watch this happen. Why? Because there’s something primal about it. It’s the one day when the sun seems to "stand still." In fact, the word "solstice" comes from the Latin solstitium—sol (sun) and sistere (to stand still).

Across the globe, other cultures did the same thing:

- The Great Pyramids of Giza are aligned so that the sun sets exactly between two of the pyramids when viewed from the Sphinx on the solstice.

- In ancient China, the solstice was associated with "Yang" or masculine energy, celebrated alongside the earth and the feminine "Yin."

- Native American tribes in the Bighorn Mountains constructed "medicine wheels" that aligned with the solstice sunrise.

The Northern vs. Southern Reality

We often speak about the solstice from a Northern perspective, but it’s a global event with opposite results. While we’re buying sunscreen and planning beach trips, people in Australia, South Africa, and Argentina are experiencing their shortest day of the year.

For them, June 21st is the winter solstice.

It’s the middle of winter, the sun barely clears the horizon, and the nights are long. When we talk about the "longest day," we’re being hemisphere-centric. If you want to experience the most extreme version of this, go to Antarctica in June. You won't see the sun at all. It’s just pitch black for months.

📖 Related: Dave's Hot Chicken Waco: Why Everyone is Obsessing Over This Specific Spot

The Science of the "Golden Hour"

If you’re a photographer or just someone who likes a good Instagram feed, the longest day of the year is basically your Super Bowl.

Because the sun is at its highest point, the shadows at noon are the shortest they will be all year. But it’s the "Golden Hour"—that period right after sunrise and right before sunset—that lasts significantly longer during the solstice weeks. Because the sun is crossing the sky at such a shallow angle relative to the horizon (especially as you move toward the poles), it takes longer for the sun to actually "disappear."

This creates a lingering twilight. In places like Scotland or Canada, the sky never truly gets "black" during the solstice. It stays a deep, navy blue for hours. Scientists call this "civil twilight," where the sun is just below the horizon, but its light is still scattering through the atmosphere.

Why This Matters for Your Health

Light isn't just about seeing where you’re going. It’s biological.

The massive influx of light during the summer solstice can actually throw your body for a loop. Our brains produce melatonin, the sleep hormone, in response to darkness. When the sun is still up at 9:30 PM, your brain doesn't get the signal to wind down. This is why people often feel a burst of "manic" energy in June. You feel like you can stay up later, do more, and sleep less.

However, there’s a flip side. The lack of darkness can lead to "solstice insomnia."

If you’re living in a high-latitude city like Seattle or London, you might find yourself waking up at 4:30 AM because the sun is already screaming through your curtains. Investing in blackout curtains isn't just a luxury in June; for many, it’s a psychiatric necessity to keep their mood stable.

How to Actually Use the Longest Day

Don't just let the day pass you by while you're staring at a spreadsheet in a windowless office. If you want to actually "feel" the longest day of the year, you have to change your geography or your perspective.

👉 See also: Dating for 5 Years: Why the Five-Year Itch is Real (and How to Fix It)

1. Check the Solar Noon

Most people think noon is 12:00 PM. It’s not. Solar noon is the exact moment the sun is at its highest point in the sky. Depending on where you live in your time zone, solar noon could be 1:00 PM or even 1:30 PM (thanks, Daylight Saving Time). Look up the solar noon for your specific zip code and go outside at that exact moment. Look at your shadow. It will be the shortest shadow you’ll cast all year.

2. Seek High Ground

The sunset on the solstice is a slow-motion event. To maximize the experience, get to an elevated point with a clear western horizon. Because of the Earth’s tilt, the sun isn't setting in the "West"—it’s setting as far Northwest as it ever will.

3. Reset Your Internal Clock

Use the extra light to recalibrate. Getting sun exposure early in the morning on the solstice can help set your circadian rhythm for the rest of the summer. It’s like a hard reset for your brain's biological clock.

4. Observe the "Stationary" Sun

For a few days before and after the solstice, the sun’s path doesn't seem to change much. If you have a specific window where the sun hits a certain spot on your floor, watch it over the week of June 21st. You’ll notice it hits almost the exact same spot every day. That’s the "standing still" part of the solstice.

The longest day of the year is a reminder that we live on a tilted, spinning rock hurtling through space at 67,000 miles per hour. It’s the one day where the geometry of the solar system becomes visible in our backyard. Whether you’re celebrating at Stonehenge or just enjoying a late dinner on the patio, it’s a moment to acknowledge that we are part of a much larger, clockwork universe.

Take advantage of the light while it’s here. Before you know it, the tilt will start heading the other way, and the shadows will start growing long again.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Find your local "Solar Noon": Use a site like NOAA’s Solar Calculator to find the exact minute the sun is highest in your town.

- Measure your shadow: At solar noon on June 21st, stand a ruler upright and measure the shadow. Compare it to a measurement taken on December 21st to see the staggering difference in the sun's angle.

- Manage your light: If you struggle with sleep, start dimming your indoor lights two hours before sunset, even if it's still bright outside, to help your brain produce melatonin despite the solstice light.