Some movies just sort of sit there on the shelf, gathering dust, while others feel more relevant the longer they age. The Long Walk Home, released back in 1990, is definitely the latter. It isn't a loud, explosive blockbuster. There aren’t any massive CGI battles or high-speed chases. Instead, it’s a quiet, almost uncomfortably intimate look at the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott.

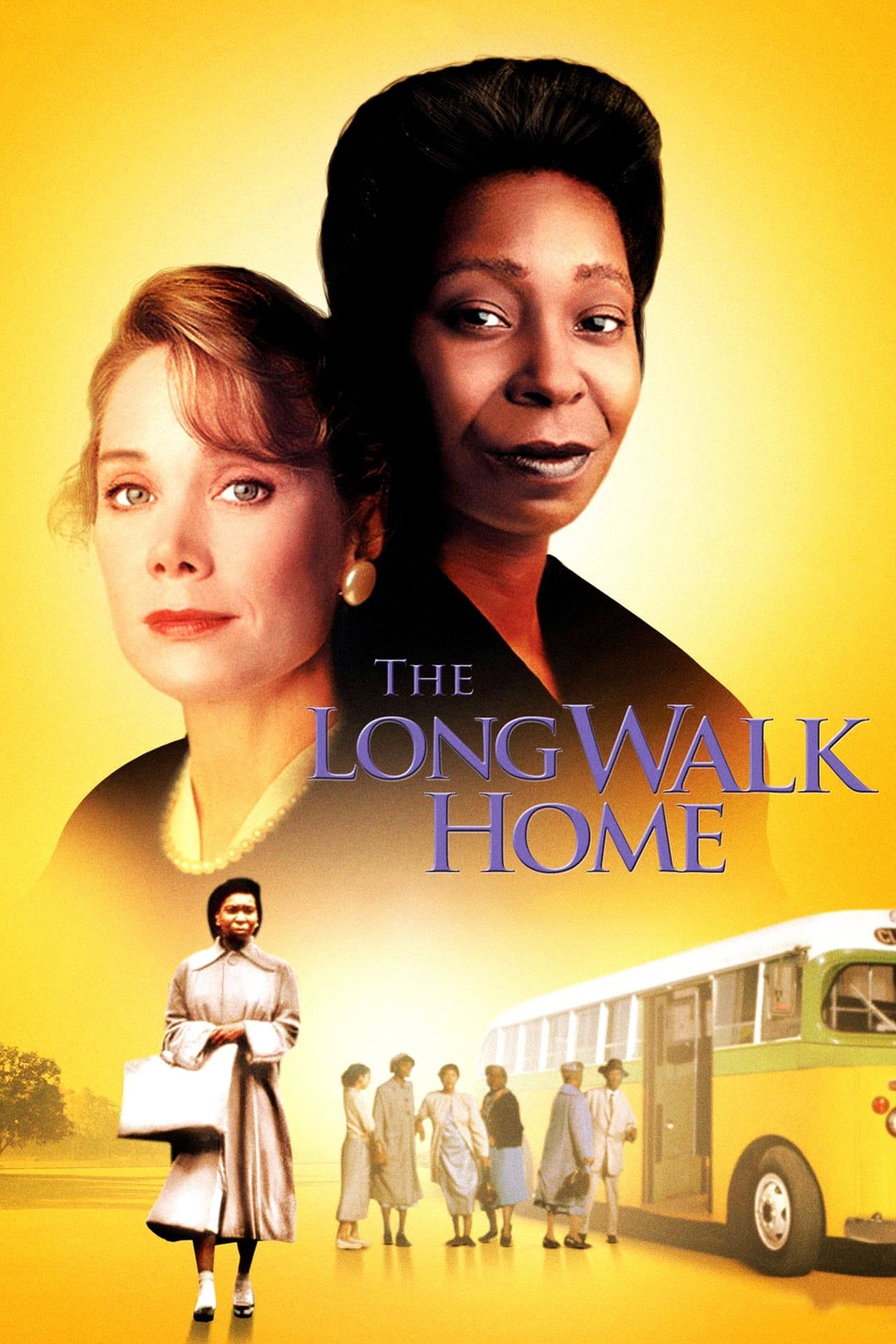

You’ve probably seen plenty of civil rights movies, right? Usually, they focus on the big names—King, Abernathy, Parks. This film does something different. It looks at the boycott through the eyes of two women who, on the surface, couldn't be more different: Odessa Cotter, played by Whoopi Goldberg, and Miriam Thompson, played by Sissy Spacek.

It's a story about walking. Literally.

When the Black community in Montgomery decided to stop riding the buses after Rosa Parks' arrest, it wasn't just a political statement. It was a massive physical undertaking. People had to get to work. They had to get to the grocery store. They had to do it in the heat, the rain, and under the constant threat of harassment. Honestly, the movie captures that physical exhaustion in a way that feels heavy. You feel the blisters.

What The Long Walk Home Gets Right About History

Most history books give you the "great man" version of events. They talk about the speeches. But history is actually made by people like Odessa. She’s a domestic worker for the Thompson family. Every day, she has to navigate the complex, unspoken rules of the Jim Crow South. When the boycott begins, she doesn't make a grand speech. She just starts walking.

Richard Pearce, the director, made a smart choice here. He didn't try to make it a biopic of a famous leader. By keeping the scope small, the stakes actually feel higher.

The film digs into the white perspective too, which is where things get messy and real. Sissy Spacek’s character, Miriam, starts out as your typical, somewhat oblivious 1950s housewife. She isn't "evil" in the way movie villains usually are. She’s just a product of her environment. She’s comfortable. But as she starts driving Odessa to work to ensure her own life stays convenient, she's forced to actually see the world through Odessa's eyes. It’s a slow-burn realization. It’s not an overnight transformation, which makes it feel much more authentic than your standard Hollywood redemption arc.

The Reality of the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott

To understand why this movie works, you have to look at the actual history it’s based on. The boycott lasted 381 days.

Think about that for a second. Over a year.

📖 Related: The A Wrinkle in Time Cast: Why This Massive Star Power Didn't Save the Movie

The Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) had to organize an incredibly sophisticated carpool system. At its peak, there were about 300 cars involved. This wasn't just some spontaneous walk; it was a logistical masterpiece. The Long Walk Home shows the tension that this organization caused within the white community. The White Citizens' Council was real, and they were terrifying. They didn't just use violence; they used economic pressure. They threatened people's jobs. They pressured insurance companies to cancel policies on the cars used in the carpools.

The film captures the fracture within the Thompson household perfectly. Miriam’s husband, Norman (played by Dwight Schultz), represents the status quo that is desperate to keep power. He isn't just worried about "tradition." He's scared. He’s scared of what happens when the social hierarchy he relies on starts to crumble.

Why the Goldberg and Spacek Dynamic Works

Whoopi Goldberg is incredible here because she plays Odessa with such restraint. We’re used to seeing Whoopi being funny or loud, but in this role, she’s a portrait of quiet dignity. You see the wheels turning in her head every time she has to bite her tongue.

Spacek is the perfect foil. Her performance is all about the cracks in the facade. You see her transition from a woman who thinks she’s "doing a favor" to someone who realizes she’s been complicit in a broken system.

It’s about the power of proximity.

When you spend hours in a car with someone, even if you’re the "boss" and they’re the "help," the humanity starts to leak through. The movie doesn't pretend they become best friends who solve racism over tea. It’s much more honest than that. It’s about the uncomfortable process of unlearning.

The Soundtrack and the Atmosphere of the South

The movie feels humid. You can almost feel the stagnant air of an Alabama summer. The cinematography by Roger Deakins—who is basically a legend in the industry—is stunning but subtle. He uses a lot of natural light, making the domestic scenes feel warm and the outdoor "walking" scenes feel exposed and vulnerable.

Then there's the music.

👉 See also: Cuba Gooding Jr OJ: Why the Performance Everyone Hated Was Actually Genius

The gospel music isn't just background noise. It’s the heartbeat of the movement. In the 1950s, the church was the only place where Black communities could gather safely and organize. The songs were a form of resistance. When the characters sing in the film, it isn't a performance; it’s a survival tactic.

Addressing the "White Savior" Critique

Is The Long Walk Home a white savior movie?

It’s a fair question to ask of any film from that era. Some critics argue that focusing so much on Miriam’s "awakening" takes the spotlight off the Black activists who were doing the actual work.

However, many film historians argue that the movie avoids the worst of these tropes because it doesn't give Miriam the credit for "saving" the movement. The movement is happening with or without her. She’s just deciding whether or not she’s going to be on the right side of history. The agency remains with Odessa and her community.

Odessa doesn't need Miriam to tell her she deserves rights. She already knows. Miriam is the one who needs to catch up.

In a way, the movie is a study of white moderate behavior, which Dr. King famously wrote about in his Letter from Birmingham Jail. It shows the danger of being more devoted to "order" than to justice.

Why You Should Watch It Today

If you’re looking for a movie that explains the grit of the civil rights movement without being a dry history lesson, this is it. It shows the cost of conviction.

It’s also a reminder that change doesn't usually happen because of one big moment. It happens because of thousands of small, exhausting choices made by ordinary people every single day.

✨ Don't miss: Greatest Rock and Roll Singers of All Time: Why the Legends Still Own the Mic

Key Takeaways from the Film

- Resistance is a marathon: The boycott lasted over a year. True change requires incredible stamina.

- The personal is political: The choices made inside a home—like who drives whom to work—have massive ripple effects.

- Silence is a choice: Staying "neutral" in the face of injustice is just a way of supporting the status quo.

- Economic power matters: The boycott worked because it hit the city where it hurt—the wallet.

Actionable Steps for Deeper Understanding

If the movie sparks an interest in this era, don't just stop at the credits.

First, read Stride Toward Freedom by Martin Luther King Jr. It’s his own account of the Montgomery boycott and it provides the intellectual and spiritual context that the movie hints at.

Second, look up the story of Jo Ann Robinson. While Rosa Parks is the famous face, Robinson and the Women’s Political Council were the ones who actually stayed up all night mimeographing thousands of flyers to start the boycott. She’s a fascinating figure who deserves just as much screen time.

Third, visit the National Memorial for Peace and Justice if you ever get the chance to go to Montgomery. It puts the events of the film into a much larger, and much more somber, historical perspective.

Finally, think about your own "long walk." What are the systems in your life that you take for granted, and what would it look like to actually step away from them, even if it’s inconvenient?

The Long Walk Home isn't just a period piece. It’s a mirror. It asks us what we’re willing to sacrifice for what’s right, and it doesn't give us an easy answer. It just shows us the road and asks if we’re ready to start walking.

Practical Insights for Viewers

- Contextualize the "Politeness": Notice how the characters interact. The "politeness" of the 1950s South was often a mask for deep-seated systemic violence.

- Focus on the Background: Pay attention to the minor characters—the neighbors, the shopkeepers, the police. They represent the collective pressure used to maintain segregation.

- Evaluate the Ending: The final scene is powerful because it isn't a "happily ever after." It’s a "beginning of the work." Use that as a lens to view modern social movements.

By engaging with the film as a piece of living history rather than just a Friday night movie, you get a much richer sense of how we got to where we are today. It’s about the weight of the pavement and the strength of the person standing on it.