Ever stared at a calculator and wondered how it actually knows what the natural log of 1.1 is? It isn't magic. It isn't just a giant look-up table stored in the silicon chip. It's calculus. Specifically, it's a power series. If you've ever dabbled in finance, physics, or data science, the log 1+x expansion—also known as the Mercator series—is basically the secret sauce that makes complex approximations possible without a supercomputer.

Most people see a Taylor series and their eyes glaze over. I get it. It looks like a bunch of x-variables and alternating signs meant to torture undergrads. But honestly, this specific expansion is one of the most elegant tools in a mathematician's belt. It allows us to turn a transcendental function, which is "hard" to calculate, into a simple polynomial, which is "easy" for a computer to handle using basic addition and multiplication.

The actual formula you're looking for

Let's get the math out of the way so we can talk about why it's cool. When we talk about the log 1+x expansion, we are usually looking at the natural logarithm, denoted as $\ln(1+x)$. The series expansion, centered at zero (which makes it a Maclaurin series), looks like this:

$$\ln(1+x) = x - \frac{x^2}{2} + \frac{x^3}{3} - \frac{x^4}{4} + \dots$$

✨ Don't miss: How to Loop Videos on YouTube: The Simple Way Everyone Misses

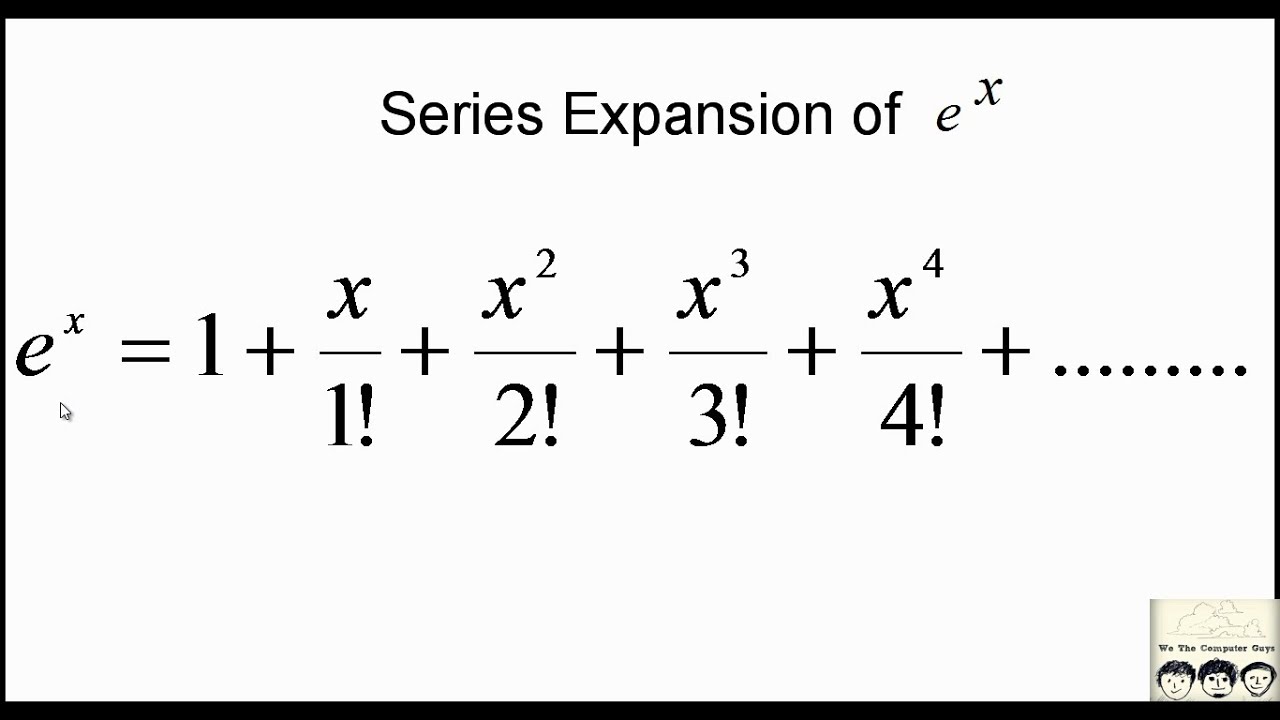

Notice something weird? Unlike the expansion for $e^x$ or $\sin(x)$, there are no factorials in the denominators here. It's just the power of $x$ divided by that same number. Also, it alternates signs. This simplicity is actually its downfall in terms of speed, which we’ll get into later.

Why do we use 1+x instead of just x?

This is the question that trips up everyone. Why not just expand $\ln(x)$? Well, if you try to find the natural log of zero, the universe basically explodes. The function is undefined there. Since Taylor series are built by taking derivatives at a specific point, and you can't take the derivative of something that doesn't exist at that point, we shift the whole thing. By using $1+x$, we center our "easy" zone around $x=0$, which corresponds to $\ln(1)$. Since $\ln(1) = 0$, we have a perfect starting line for our approximation.

The catch: The radius of convergence

Here is where it gets spicy. You can't just plug any number into this expansion and expect it to work. If you try to calculate the log of 10 using this series by plugging in $x = 9$, the numbers will get bigger and bigger until they hit infinity. It's useless.

The log 1+x expansion only works—or "converges"—when $x$ is between -1 and 1. Specifically, $-1 < x \le 1$. If you step outside that tiny window, the math falls apart. This is why mathematicians like Brook Taylor and Nicholas Mercator are so famous; they figured out exactly where these "fences" sit. If you need to find the log of a large number, you have to use clever logarithmic properties to pull that number back into the "safe zone" of -1 to 1.

Real-world vibes: Compound interest and physics

Why should you care? If you're in finance, this series is the backbone of understanding small changes in interest rates. When an interest rate $r$ is very small, $\ln(1+r)$ is approximately just $r$. That first term of the expansion is doing all the heavy lifting.

✨ Don't miss: Does the US Have Hypersonic Missiles? The Messy Reality of the American Race for Mach 5

In physics, specifically when dealing with entropy or statistical mechanics, you often see terms like $\ln(1+\epsilon)$ where $\epsilon$ is some tiny fluctuation. Instead of hauling around a heavy logarithmic function in your equations, you just swap it for $x - \frac{x^2}{2}$ and move on with your life. It makes the unsolvable solvable.

It’s slow. Like, really slow.

Honesty time: the log 1+x expansion is kind of a "lazy" series. In the world of numerical analysis, we talk about "rate of convergence." Some series get to the right answer in three steps. This one? It takes its sweet time. Because there are no factorials in the denominator to make the terms get small quickly, you need to calculate a lot of terms to get a high degree of accuracy.

If you're writing code for a high-frequency trading algorithm or a high-fidelity physics engine, you probably aren't using the raw Mercator series. You're likely using a transformed version, like the inverse hyperbolic tangent substitution, which converges way faster. But the log 1+x expansion remains the fundamental ancestor of those faster methods.

How to actually use this today

If you're trying to implement this in a Python script or just trying to pass a Calc 2 exam, remember the "alternating" part. It’s easy to forget that minus sign on the even powers.

- Check your $x$ value. Is it between -1 and 1? If not, stop.

- Determine how much precision you need. Usually, four or five terms are enough for a "good enough" estimate.

- Watch the signs. Odd powers are positive, even powers are negative.

There's a certain beauty in realizing that the complex curves of a logarithm can be flattened out into a simple string of subtractions and additions. It's the ultimate hack for understanding how numbers grow.

📖 Related: The McDonnell Douglas A-12 Avenger II: Why the Flying Dorito Failed So Hard

Actionable next steps for the math-curious

- Verify it yourself: Grab a calculator. Compute $\ln(1.1)$. Then, manually calculate $0.1 - \frac{0.1^2}{2} + \frac{0.1^3}{3}$. See how close you get with just three terms.

- Explore the "Big O": If you're into computer science, look up "Big O notation" for Taylor series. It helps you quantify exactly how much error you're inviting in when you truncate the series.

- Test the limits: Try plugging $x = 1$ into the series. You'll get $1 - 1/2 + 1/3 - 1/4 \dots$, which is the famous Alternating Harmonic Series. It actually converges to $\ln(2)$, which is a pretty mind-blowing connection between simple fractions and transcendental numbers.

The log 1+x expansion isn't just a textbook artifact. It's a bridge between the world of continuous curves and the world of discrete, programmable logic. Once you see it, you start seeing it everywhere.