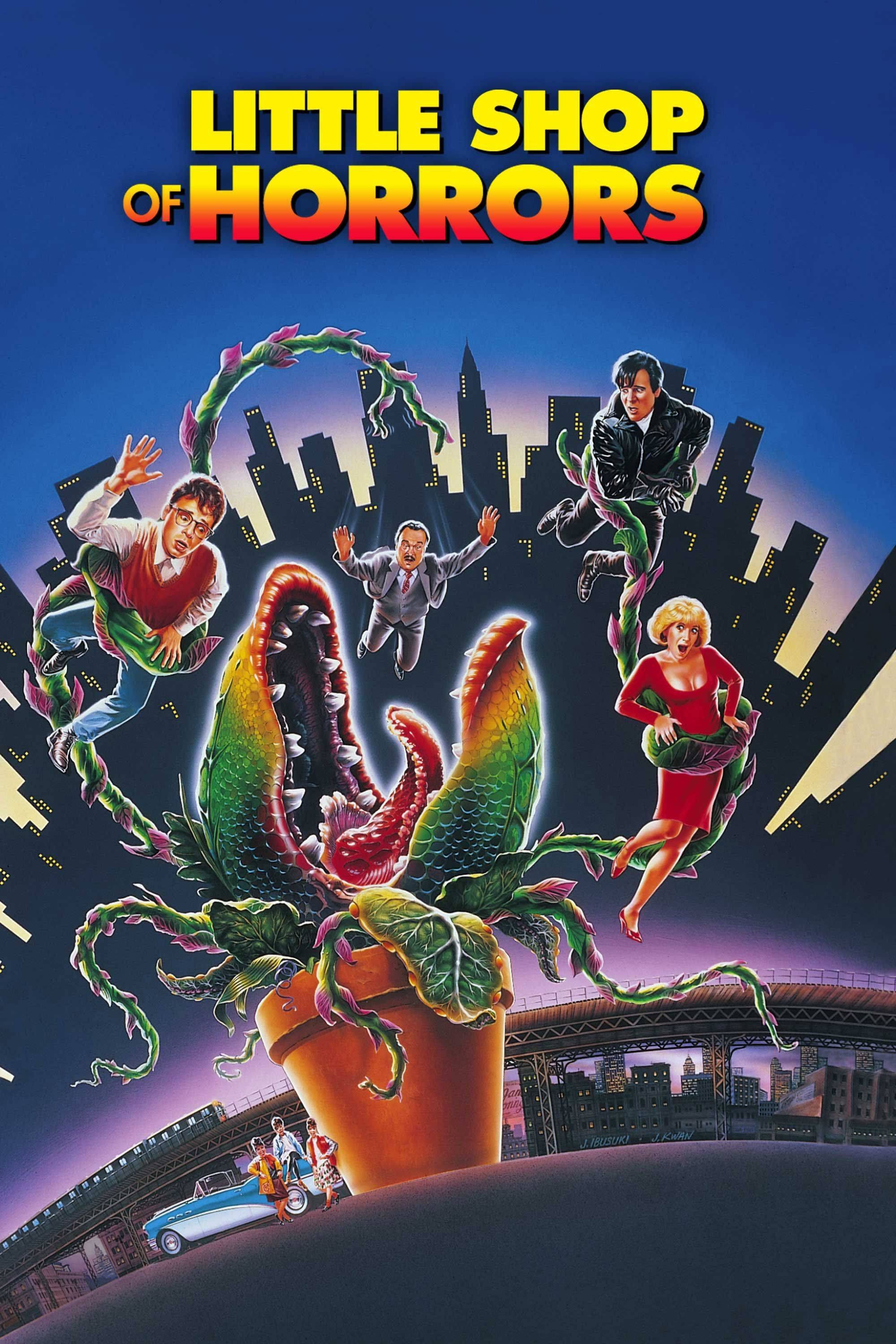

Honestly, if you sit down and actually read the Little Shop of Horrors screenplay, you realize pretty quickly that Howard Ashman wasn’t just writing a musical; he was writing a tragedy disguised as a cartoon. Most people know the 1986 Frank Oz movie. They know Rick Moranis, the catchy Motown tunes, and that giant, foul-mouthed flytrap. But the script itself? It’s a fascinating, messy, brilliant evolution of a story that started as a low-budget 1960 cult flick and ended up becoming one of the most debated pieces of writing in musical theater and film history.

It’s weird.

It's dark.

And depending on which version of the script you’re holding, it either ends with a happy wedding or the literal apocalypse.

The Howard Ashman magic and the 1960 roots

Before it was a big-budget Warner Bros. production, it was a Roger Corman movie shot in two days. Seriously, two days. The original 1960 Little Shop of Horrors screenplay by Charles B. Griffith was a shoestring-budget black comedy about a guy named Seymour who accidentally feeds people to a plant. When Howard Ashman took that premise in the early 80s for the Off-Broadway stage, he did something nobody expected. He gave it a soul.

Ashman’s genius wasn't just adding songs. He transformed Seymour from a bumbling idiot into a sympathetic loser trapped by his own poverty. He took Audrey, who could have been a caricature, and turned her into a tragic figure dreaming of a "tract house" with plastic on the furniture. When you read the dialogue in the screenplay, you see the precision. Ashman was a master of "patter"—that fast-paced, rhythmic way of speaking that mirrors the 1960s doo-wop and rock-and-roll score.

He understood Skid Row. He understood that for the horror to work, the hunger had to feel real. Not just the plant's hunger for blood, but Seymour’s hunger for a way out.

👉 See also: Is Heroes and Villains Legit? What You Need to Know Before Buying

The ending that almost killed the movie

We have to talk about the ending. This is the biggest point of contention for anyone studying the Little Shop of Horrors screenplay.

In the original stage script and the initial draft for the 1986 film, Audrey II wins. The plant eats Audrey. Then it eats Seymour. Then it reproduces, and giant Venus Flytraps take over the world, crushing buildings and eating New York City while a Greek chorus warns the audience "Don't Feed the Plants!"

They actually filmed this. It cost millions.

But when they screened it for audiences? They hated it. Frank Oz once mentioned that the test audience in San Jose went from cheering after every song to dead silence by the time the credits rolled. They loved the characters so much that watching them die was a visceral gut-punch they couldn't handle.

So, they rewrote it.

The "happy ending" we see in the theatrical cut—where Seymour electrocutes the plant and moves to the suburbs with Audrey—was a last-minute pivot. If you compare the two versions of the script, the tonal shift is jarring. The original screenplay is a cynical cautionary tale about greed and selling your soul. The theatrical movie is a weird, quirky rom-com where the monster loses.

✨ Don't miss: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

Why the "Directors Cut" script is better (and worse)

Technically, the "unhappy" screenplay is more artistically consistent. It follows the logic of a Faustian bargain. If you sell your soul to a blood-drinking plant to get the girl and the fame, you shouldn't get to keep the girl and the fame.

However, looking at it through a modern lens, you can see why the rewrite worked. Rick Moranis brought a vulnerability to the role that made the original ending feel almost too cruel. Sometimes the script has to bend to the actor.

Technical brilliance in the dialogue

If you look at the screenplay’s structure, it’s remarkably tight. There’s almost no "fat" in the writing. Every scene either raises the stakes of Seymour’s guilt or increases the plant’s power.

Think about the character of Orin Scrivello, D.D.S. He’s a nightmare. The screenplay describes him with a terrifying intensity—a man who loves causing pain. In the hands of Steve Martin, it’s hilarious, but on the page, it’s genuinely dark. The script uses his death as a turning point. Seymour doesn't kill him, but he doesn't save him either. It’s that moral gray area that makes the Little Shop of Horrors screenplay stand out from typical 80s comedies.

- Seymour’s internal conflict: "The plant is growing... but at what cost?"

- Audrey’s "Somewhere That’s Green": A masterclass in "I Want" songs.

- The plant’s manipulation: Audrey II doesn't just bark orders; it seduces.

It’s basically Macbeth with a giant puppet.

The script’s legacy in 2026 and beyond

People are still obsessed with this story. There have been talks of a remake for years—Chris Evans was rumored for the dentist at one point—but it always comes back to the writing. How do you balance the camp of a singing plant with the genuine tragedy of domestic abuse (Audrey’s story) and systemic poverty?

🔗 Read more: Why American Beauty by the Grateful Dead is Still the Gold Standard of Americana

The screenplay manages this by never winking at the camera. It treats the plant as a real threat. It treats the characters' pain as real pain.

If you’re a writer or a film buff, studying the Little Shop of Horrors screenplay is a lesson in adaptation. It shows how to take a "B-movie" concept and give it enough heart to live on Broadway for decades. It also teaches you that sometimes, the audience is right—and sometimes, the creator’s original, dark vision is the one that sticks in your brain forever, even if it didn't make the final cut.

Actionable ways to study the screenplay

If you want to actually understand how this script works, don't just watch the movie. You’ve gotta get into the weeds.

- Compare the 1960 and 1986 scripts: Notice how Ashman kept the names but changed the motivations. In 1960, it’s just chaos. In 1986, it’s a character study.

- Read the "Lost" Ending: You can find the original 23-minute ending online now. Read the script while watching it. Notice how the lyrics of the finale "Don't Feed the Plants" hit differently when the world is actually ending.

- Analyze the "Feed Me" Scene: This is the core of the script. It’s a negotiation. Watch how the plant uses Seymour’s insecurities against him. It’s a perfect example of how to write a "villain" who is actually a mirror of the protagonist.

- Look for the subtext: Skid Row isn't just a setting; it's a character. The script emphasizes the "forgotten" nature of these people. Use that as inspiration for your own world-building—how does the environment force your characters to make bad choices?

The real magic of the Little Shop of Horrors screenplay is that it refuses to be just one thing. It's a comedy, a horror, a tragedy, and a love letter to 60s pop culture all at once. And that's why we're still talking about it.

Next Steps for Enthusiasts:

To truly grasp the impact of Ashman's work, your next move is to track down the Off-Broadway script (the "Acting Edition"). Unlike the film, the stage version is the purest form of the story's cynical heart. Pay close attention to the stage directions for Audrey II’s growth; they reveal the technical nightmare of bringing a script like this to life before CGI existed. Once you’ve read that, watch the 2012 restored ending of the film to see exactly where the written word and the visual spectacle collided—and why it almost bankrupted the production.