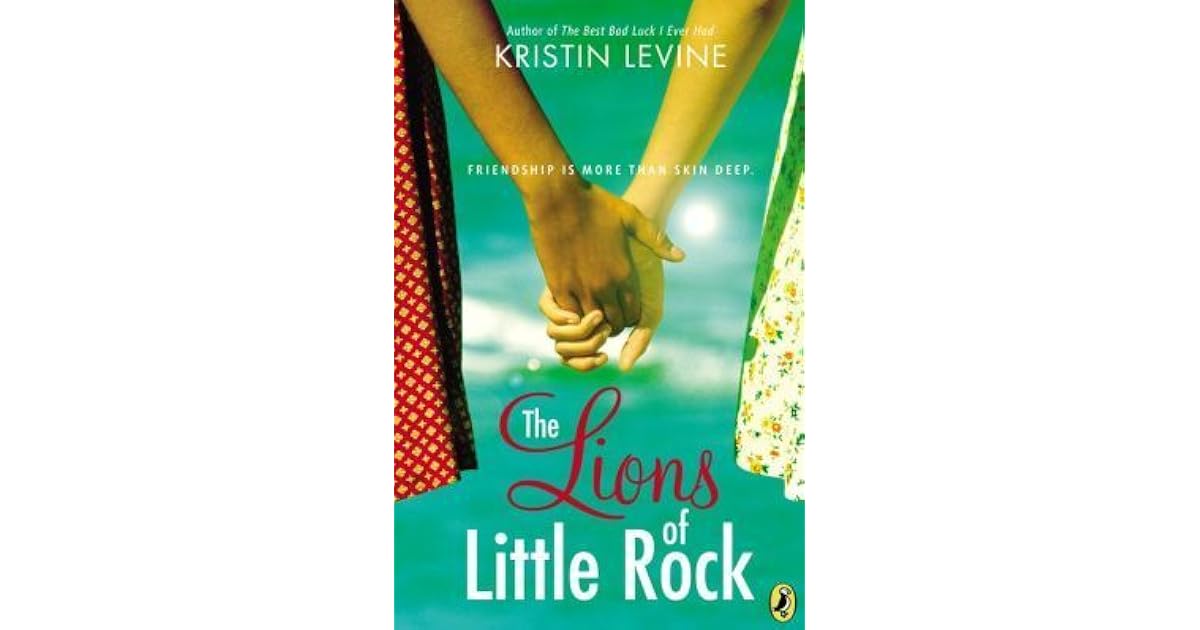

History isn't always about big, booming voices or statues in the town square. Sometimes, it’s about a twelve-year-old girl who’s too scared to speak in class. That is basically the heartbeat of Kristin Levine’s historical fiction novel.

If you haven't picked up The Lions of Little Rock book yet, you might think it’s just another school assignment or a dry retelling of the 1957 integration of Central High. It isn’t. Honestly, it’s way more intimate than that. It’s set in 1958, during what people in Arkansas call "The Lost Year." That’s the year the governor actually closed all the high schools in Little Rock just to stop integration from happening.

It was a mess.

Marlee, our main character, is quiet. Like, "won't talk to anyone but her family" quiet. She counts things—primes, specifically—to stay calm. Then she meets Liz. Liz is bold, funny, and seemingly the only person who can coax Marlee out of her shell. But then Liz disappears from school overnight because people find out she’s "passing" for white.

Suddenly, Marlee’s quiet world is on fire.

The Reality of the Lost Year in Little Rock

Most people know about the Little Rock Nine. We’ve seen the black-and-white photos of Elizabeth Eckford walking through a screaming mob. But fewer people talk about the year after that. In 1958, Governor Orval Faubus was so desperate to prevent Black students from attending school with white students that he shut the whole system down. Imagine being a teenager and your school just... vanishes.

Levine doesn't sugarcoat the tension. The book captures that weird, suffocating atmosphere where neighbors started spying on neighbors. In the story, Marlee’s father is a teacher who wants to do the right thing, while her mother is a member of the Women’s Emergency Committee to Open Our Schools (WEC). This was a real group, by the way. It was started by Vivion Brewer and other local women who were tired of their kids' education being used as a political football.

They were brave. They faced death threats just for saying kids should be in school.

✨ Don't miss: Am I Gay Buzzfeed Quizzes and the Quest for Identity Online

Why Marlee and Liz Matter So Much

Friendship in The Lions of Little Rock book is the catalyst for everything. Liz teaches Marlee how to find her voice, and in return, Marlee has to find the courage to keep their friendship alive when it becomes literally dangerous to do so. They meet at the zoo, near the lion exhibit—hence the title. The roaring of the lions is this heavy, obvious metaphor for the voices that need to be heard, but it works. It really works.

The relationship isn't perfect. It’s messy. Marlee has to unlearn a lot of the casual, systemic racism she grew up breathing in like oxygen.

She's a math whiz.

She views the world through numbers because numbers are stable. 1+1 always equals 2. But in 1958 Arkansas, the logic of her world was breaking. Why could she be friends with Liz on Tuesday but not on Wednesday? Why were people throwing sticks of dynamite into houses?

Facts vs. Fiction: What Levine Got Right

Levine actually based some of the characters on her own family history. Her mother grew up in Little Rock during this era, which is probably why the setting feels so lived-in. The details about the "STOP" (Stop This Outrageous Purge) campaign are real. The purge refers to when the school board fired over 40 teachers and administrators because they were suspected of being integrationists.

It was a witch hunt.

You see this through Marlee’s eyes as she watches her dad’s job security vanish. It makes the stakes feel massive because, for these families, they were.

🔗 Read more: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

- The WEC: The Women’s Emergency Committee was the first white organization to publicly stand up against the school closures.

- The Dynamite: Bombings and threats were a terrifyingly common tactic used by segregationists to intimidate activists.

- The Social Divide: The book shows how even families were split down the middle, with siblings and spouses fighting over whether "tradition" was worth more than equality.

Addressing the Common Misconceptions

Some readers think this is "just" a middle-grade book. That’s a mistake. While the language is accessible, the themes of complicity and silence are pretty heavy. There's this idea that everyone back then was either a "good guy" or a "bad guy." Levine shows the gray area. She shows the people who were "kinda" okay with things as long as they didn't have to get their hands dirty.

That’s the most uncomfortable part of the book, honestly. Watching Marlee realize that some of the people she loves are choosing silence over justice. It forces the reader to wonder what they would have done in that same position.

Would you have risked your house? Your job? Your social standing?

It's easy to say "yes" from 2026. It was a lot harder in 1958.

The Writing Style and Impact

Levine’s prose is direct. It’s not flowery. It matches Marlee’s personality perfectly. You get these short, punchy observations about people that feel like something a kid would actually think. For example, Marlee describes people by the type of drink they are. Some are cold water; some are hot chocolate; some are bitter tea.

It’s a clever way to show a character who is constantly analyzing everyone around her because she’s too afraid to join the conversation.

The pacing picks up significantly in the second half. What starts as a quiet story about a shy girl turns into a high-stakes drama involving secret meetings, car chases, and a literal bomb. It’s a lot. But it never feels like it's "doing too much" because the emotional core stays focused on whether Marlee can finally speak up.

💡 You might also like: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

Actionable Steps for Readers and Educators

If you’re planning to read The Lions of Little Rock book or use it in a classroom, don’t just stop at the final page. There’s a lot of supplementary history that makes the story hit harder.

First, look up the actual archives of the Women’s Emergency Committee. Seeing the names of the real women who organized the vote to reopen the schools adds a layer of weight to the fictional characters of Marlee’s mother and her friends. You can find these records through the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UALR) Center for Arkansas History and Culture.

Second, compare the events in the book to the "Little Rock Nine" events of the previous year. Understanding the escalation from 1957 to 1958 is crucial. The closure of the schools was an act of desperation by a government that had lost in court and was trying to win by destroying the system entirely.

Third, use the "drink analogy" from the book to talk about character traits. It’s a great way for younger readers to engage with complex personalities. Ask: "If this person is a cup of black coffee, what makes them that way?"

Finally, visit the Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site if you're ever in the area. It’s still a functioning high school, which is wild to think about. Standing on those grounds helps you realize that 1958 wasn't that long ago. The people who lived through this are still around. Their stories are still being told.

The book isn't just a history lesson; it's a manual on how to be brave when you're terrified. That never goes out of style. It’s about the fact that your voice has power, even if it’s small, even if it shakes when you use it. Marlee’s journey from a silent observer to a girl who can stand up to a bully—and a system—is something everyone needs to see.

Read it with a notebook nearby. You’re going to want to look things up. You’re going to want to talk about it. And honestly, that’s exactly what a great book should do. It should make you louder.