You know that feeling when you open a book and it just smells like childhood? That's Narnia for a lot of us. But if you actually sit down and look at The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe characters, they aren't just flat cutouts from a Sunday school lesson. C.S. Lewis was doing something way more interesting than just writing a "kids' story." He was digging into how people—real, messy, flawed people—react when they’re dropped into a world that doesn’t make sense. Honestly, the Pevensies are kind of a wreck at the start. They’re displaced war refugees. That's a heavy way to begin a "fairy tale."

The Pevensies: More Than Just Four Siblings

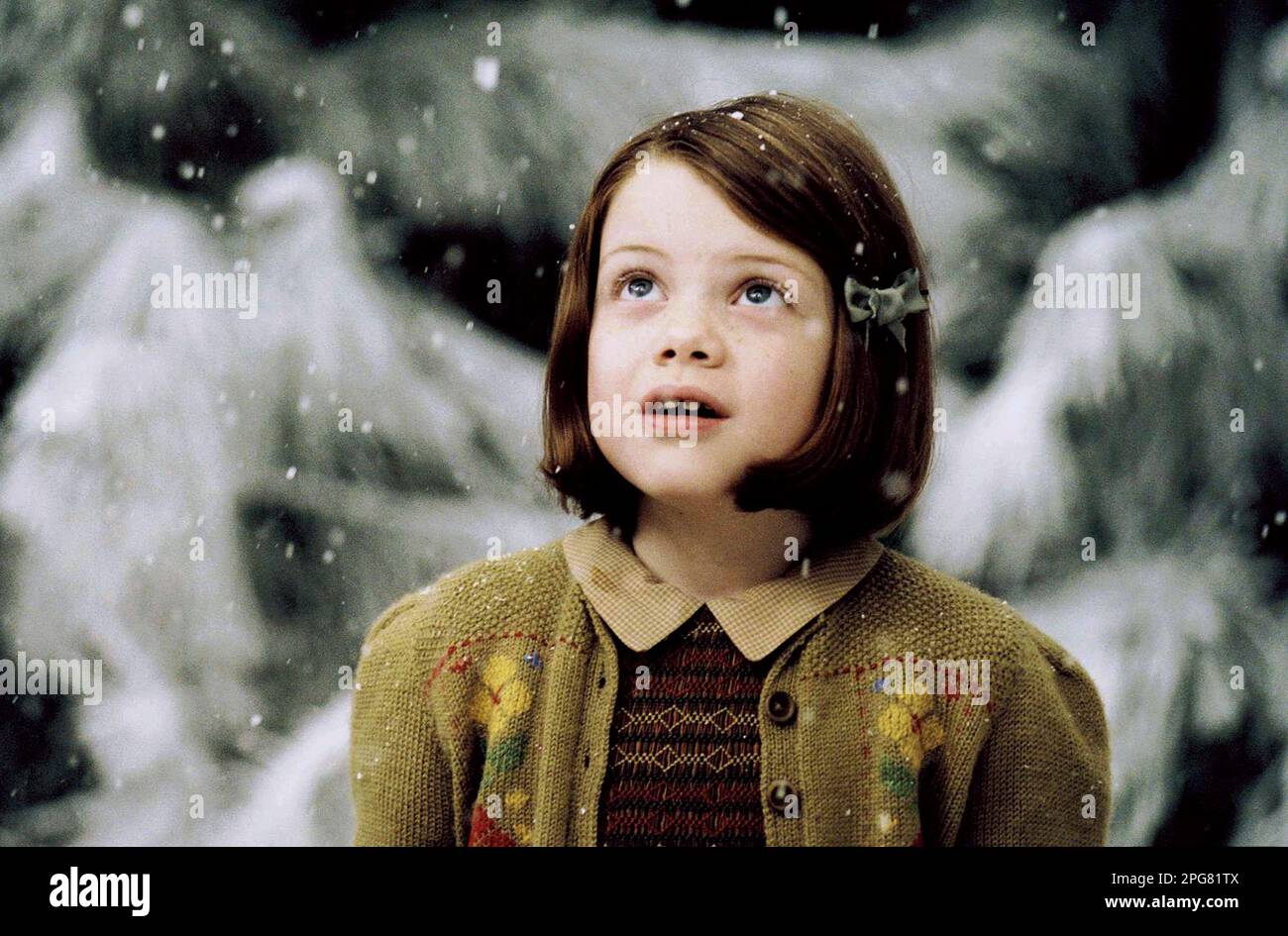

Lucy is usually everyone’s favorite. She’s the "soul" of the group. But she’s not just "the cute one." She’s actually the bravest because she trusts her gut when everyone else is gaslighting her. When she first steps through that wardrobe, she isn't looking for a kingdom. She's just curious. Lewis based a lot of her wonder on his own goddaughter, Lucy Barfield.

Then you've got Edmund.

Edmund is the most "human" character in the whole book. He’s a jerk, sure. He’s spiteful and he’s dealing with some serious middle-child syndrome. But his betrayal isn't because he’s evil. It’s because he’s hungry and he wants to feel important. Turkish Delight is a weird choice for a soul-selling bribe, but in the context of post-war sugar rationing in England, it makes total sense. To a kid in 1950, a box of high-end candy was basically a fortune.

Peter and Susan are the "grown-ups" who aren't actually grown-ups. Peter has the weight of being the "High King," but he’s really just a teenager who has to kill a wolf with a sword he barely knows how to hold. Susan is the one people argue about the most. She’s the logical one. In this first book, she’s the voice of caution, the one who wants to go home because staying in a frozen woods with a talking beaver is, objectively, a bad idea.

The Dynamics of a Broken Family

It’s easy to forget they were sent away because of the Blitz. They’re traumatized.

🔗 Read more: Evil Kermit: Why We Still Can’t Stop Listening to our Inner Saboteur

- Peter tries to be the dad.

- Susan tries to be the mom.

- Edmund rebels against the fake authority.

- Lucy just wants everyone to be happy.

The White Witch and the Logic of Winter

Jadis isn't just a "bad guy." She is the embodiment of "stasis." She’s what happens when someone wants power so badly they’d rather everything be frozen and dead than out of their control. She doesn't just want to rule; she wants to stop time. That "Always winter, never Christmas" line is one of the most depressing sentences in literature. It’s a total lack of hope.

She’s tall, she’s pale, and she’s terrifying because she’s actually very beautiful. Lewis was tapping into the idea that evil doesn't always look like a monster. Sometimes it looks like a queen offering you snacks. Tilda Swinton’s portrayal in the 2005 movie nailed that "cold as ice" vibe, but in the book, she’s almost more of a psychological predator. She knows exactly how to manipulate Edmund’s insecurities.

Aslan: The Lion Who Isn't Tame

If you ask anyone about The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe characters, they’re going to mention the lion. Obviously. But there’s a nuance to Aslan that gets lost in the "He’s just Jesus" comparisons. Yes, the allegory is 100% there—Lewis didn't hide it. But Aslan is also "not a tame lion."

That phrase is crucial.

It means he’s dangerous. He’s not a pet. He’s not a safe, cuddly toy. He represents a type of power that is good but also terrifying. When the kids first hear his name, they feel a shift in their chest. It’s like a jump-scare but for your soul. He’s the catalyst. He doesn't fix everything with a magic wand; he demands that the kids step up and fight their own battles, even while he’s doing the heavy lifting behind the scenes.

💡 You might also like: Emily Piggford Movies and TV Shows: Why You Recognize That Face

The Supporting Cast: Mr. Tumnus and the Beavers

We have to talk about Mr. Tumnus. He’s the first "person" Lucy meets, and he’s a kidnapper. Let’s be real. He’s literally there to lure her back to his cave to hand her over to the Witch. The reason we love him is because he has a conscience. He’s a "good" person caught in a "bad" system. His redemption arc is tiny, but it’s the spark that starts the whole revolution.

Then you have the Beavers.

They’re the working class of Narnia.

They’re cozy.

They have a sewing machine and they catch fish.

They provide the grounding for the story. Without them, Narnia is just a weird dreamland. With them, it’s a place where people live, eat, and hide from the secret police. The Beavers represent the "underground" resistance. They aren't warriors, but they know the paths and they know the prophecy.

Why This Mix of Characters Actually Works

The reason this book survived while other 1950s fantasies died out is the balance. You have the cosmic (Aslan), the terrifying (The Witch), the ordinary (The Beavers), and the relatable (The Pevensies). It’s a spectrum of morality.

Most people get the "Turkish Delight" thing wrong, by the way. They think Edmund is just greedy. In reality, Lewis was writing about addiction. Once you eat the Witch’s food, you don’t just want more—you need more. It’s a craving that replaces love. That’s a pretty sophisticated theme for a book about a wardrobe.

Surprising Facts About the Characters

- The Professor was actually based on W.T. Kirkpatrick, a tutor who taught Lewis how to argue logically.

- Maugrim, the wolf, represents the "Secret Police" (think Gestapo vibes), making the threat feel very real for kids who just survived WWII.

- Father Christmas shows up, which actually annoyed J.R.R. Tolkien. Tolkien hated that Lewis mixed mythologies (Santas, Fauns, and Lions), but Lewis didn't care. He wanted a "kitchen sink" approach to magic.

The Reality of the "End"

When the Pevensies grow up in Narnia, they change. They become Kings and Queens. They forget England. The tragedy—or the weirdness—of the ending is that they stumble back through the wardrobe and become kids again. They lose decades of experience in a second. That’s a lot for a child's brain to handle. It’s a bittersweet victory.

📖 Related: Elaine Cassidy Movies and TV Shows: Why This Irish Icon Is Still Everywhere

If you’re looking to really understand the depth of these characters, you have to look at them through the lens of Lewis's own life. He was a man who lost his mother young, fought in the trenches of World War I, and lived through the bombings of World War II. When he writes about a world at war and a lion who offers hope, he isn't being cute. He’s being desperate.

To get the most out of these characters today, try these steps:

- Read the book with a map. Understanding the geography of the Stone Table versus Cair Paravel makes the Pevensies' journey feel much more like a strategic military campaign than a random hike.

- Watch the 2005 film for the visuals, but read the book for the internal monologue. The movie handles the action well, but only the book explains why Edmund feels so small next to Peter.

- Look for the "Shadows." Pay attention to characters like the Dwarf or the statues in the Witch's house. They represent the collateral damage of a dictatorship.

Narnia isn't just a place to escape to. It’s a mirror. Each character represents a different way we handle fear, power, and the "long winter" of our own lives. Whether you're a "Lucy" who believes or an "Edmund" who needs a second chance, there’s a seat for you at the table. Or at least a bit of fish and chips at the Beavers' house.

Next Steps for Narnia Fans

To truly grasp the evolution of these characters, your next step should be reading The Horse and His Boy. It takes place during the Golden Age while the Pevensies are still adults ruling Narnia. Seeing Susan and Edmund as actual diplomats and kings gives you a completely different perspective on their growth compared to their "kid versions" in the first book. Also, look into the Inklings—the writing group featuring Lewis and Tolkien—to see how their debates shaped the "un-tame" nature of Aslan.