Florence in the early sixties was basically a dreamscape. You’ve got the sun hitting the marble of the Duomo, the Vespas buzzing through narrow alleys, and that specific golden hue that makes everyone look like a movie star. It's exactly where the 1962 Light in the Piazza film takes us, but don't let the postcard aesthetic fool you. This isn't just another Roman Holiday knockoff or a breezy Technicolor vacation. Honestly, it’s one of the most uncomfortable, ethically murky, and beautifully acted dramas of that era. It tackles things that 1960s Hollywood usually swept under the rug, specifically the intersection of intellectual disability, maternal overprotection, and the desperate desire for a "normal" life.

The story is simple on the surface but pretty haunting once you dig in. Meg Johnson (played by Olivia de Havilland) is vacationing in Italy with her daughter, Clara (Yvette Mimieux). Clara is gorgeous. She’s radiant. She’s also—due to a childhood accident involving a pony—living with the mental capacity of a ten-year-old. When a handsome Italian named Fabrizio falls head over heels for her, Meg has to decide: does she tell the truth and ruin her daughter’s one shot at a "standard" life, or does she let the marriage happen, effectively deceiving a whole family?

The 1962 Light in the Piazza film vs. The Broadway Musical

Most people under forty probably know the name because of the Adam Guettel musical that swept the Tonys in the mid-2000s. That show is a masterpiece of high-art theater, but the Light in the Piazza film is a different beast entirely. Directed by Guy Green, it relies on the silent glances of Olivia de Havilland. She’s the anchor. While the musical uses soaring, complex scores to show us Clara’s internal world, the film forces us to watch Meg's internal crisis.

👉 See also: What Year Was John Wayne Born: The Real Story Behind the Legend

De Havilland was a pro at this. You can see the gears turning in her head as she weighs the morality of her choice. It’s also worth noting how the movie treats Florence. In the musical, the city is a character. In the film, it’s almost an antagonist. The beauty of the plaza makes Clara’s "imperfection" feel more tragic to Meg. The contrast is sharp. You see the ancient, "perfect" statues of Florence and then you look at this young woman who is "broken" in the eyes of the 1960s medical establishment. It’s heavy stuff for a movie that looks this pretty.

Yvette Mimieux and the Difficulty of Portraying Clara

How do you play "innocence" without it becoming a caricature? That was the massive hurdle for Yvette Mimieux. In the Light in the Piazza film, she has to balance being a romantic lead with the reality of Clara's condition. If she’s too "slow," the romance feels predatory. If she’s too "normal," Meg’s frantic worrying seems like madness.

Mimieux hits this weird, ethereal sweet spot. She’s impulsive. She’s joyful. But then you see her get overwhelmed by a simple task or a fast conversation, and the reality sets back in. It’s a performance that holds up surprisingly well, even if our language around neurodivergence has changed drastically since the early sixties. Back then, they used words like "child-minded." Today, we’d have a much more nuanced diagnosis. But the film doesn't get bogged down in medical jargon. It stays in the emotional trenches.

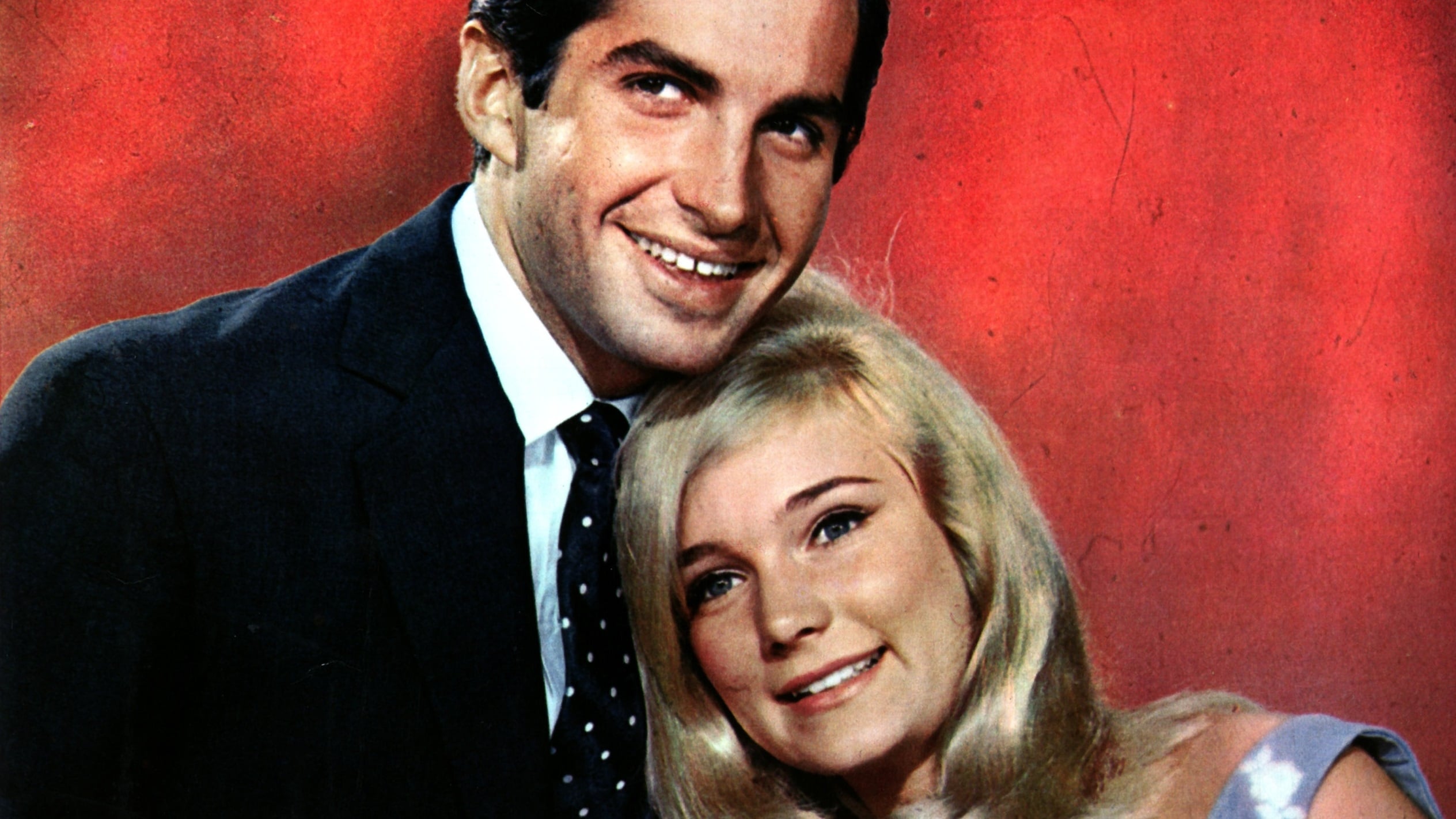

The chemistry between Mimieux and George Hamilton (who plays Fabrizio) is actually quite sweet. Hamilton, before he became the king of the tan, was actually a decent dramatic actor. He plays Fabrizio with a blind, youthful passion. He doesn't see Clara's "slowness" as a deficit; he sees it as a purity of spirit. It’s a fascinating take because it makes you wonder: is he the only one seeing her correctly, or is he just too naive to understand the lifelong commitment he’s making?

The Moral Gray Area That Makes You Squirm

The movie doesn't give you an easy out. It’s not a "happily ever after" flick in the traditional sense.

🔗 Read more: Patrick Star I Love You GIF: Why This Weird 2002 Moment Still Rules Your Group Chat

Think about it.

Meg is essentially lying by omission. She is allowing a man to marry a woman who cannot fully understand the legal or social ramifications of marriage. Her husband back in the States, played by Rossano Brazzi, is the cynical voice of reason. He wants Clara put in a school. He thinks Meg is delusional. It’s a brutal dynamic. You’ve got the "cold" father who sees the reality and the "loving" mother who is willing to commit a massive deception to give her daughter a moment of joy.

Who is the villain? Nobody. Everybody.

- Meg is protecting her child from a lonely life in an institution.

- The father is protecting the family's reputation and Clara’s own safety.

- The Italians just want a beautiful bride for their son.

The Light in the Piazza film leans into this tension. There’s a scene where Meg tries to confess to Fabrizio’s father, and she just... can’t. The language barrier, the social pressure, the sheer beauty of the moment—it all conspires to keep the secret buried. It makes the viewer an accomplice. You want Clara to be happy, but you feel the weight of the lie in your gut.

Production Value and the MGM Touch

This was an MGM production, and it shows. They didn't just build a set in California. They went to Florence. They went to Rome. The cinematography by Otto Heller is lush. He used the "Eastmancolor" process, which gave the film that specific saturated look that defines early 60s cinema.

The costumes are also doing a lot of work. Notice how Meg is always buttoned up, dressed in structured, darker colors, while Clara is almost always in light, flowing fabrics. It visualizes the weight Meg is carrying versus the lightness Clara is allowed to feel. It’s subtle, but it works.

If you watch the Light in the Piazza film today, you’ll notice the pacing is slower than modern audiences might like. It lingers. It lets the silence between mother and daughter hang in the air. This wasn't a "fast-paced" thriller; it was a psychological character study disguised as a travelogue.

Why We Still Talk About This Story

The longevity of Elizabeth Spencer’s original novella, which this film is based on, is incredible. It’s been a movie, a stage play, and a world-class musical. Why? Because the central question is universal: What would you do to ensure your child isn't alone in the world?

In the Light in the Piazza film, the stakes are heightened because of the era. In 1962, a woman like Clara had very few options. There was no "independent living" or "inclusive workplace." It was either a sheltered life with parents or an institution. Meg’s choice, while deceptive, is a desperate attempt to bypass a cruel system.

Honestly, the ending of the film feels like a cliffhanger, even if the credits roll. We see the wedding. We see the celebration. But as a viewer, you’re left wondering what happens six months later. What happens when the "honeymoon" phase ends and the reality of Clara’s needs becomes apparent to Fabrizio? The film doesn't answer that. It leaves the "light" in the piazza, letting the shadows fall elsewhere.

Getting the Most Out of Your Viewing

If you're planning to watch the Light in the Piazza film for the first time, or if you're revisiting it after seeing the musical, keep a few things in mind to really catch the nuance.

First, pay attention to the secondary characters. The Italian family isn't just a monolith. Fabrizio's father (Rossano Brazzi again, playing a double-ish role in the vibe of the film) represents an old-world view of lineage and marriage. He’s obsessed with the dowry and the "appropriateness" of the match. It adds a layer of class commentary that often gets missed.

Second, look at the "accidents." The way the film depicts Clara’s moments of confusion is very specific. It’s usually triggered by noise, crowds, or high-pressure social expectations. It’s a very grounded way to show a brain that processes information differently.

Finally, compare it to other films of 1962. This was the year of Lawrence of Arabia and To Kill a Mockingbird. Cinema was shifting toward "big" themes and social justice. The Light in the Piazza film fits right into that shift, even if it looks like a romance on the poster. It’s asking "what is a life worth?" just as much as any gritty courtroom drama.

Actionable Steps for Film Enthusiasts

To truly appreciate the context and impact of this film, you should explore it through a few different lenses:

- Read the Source Material: Pick up Elizabeth Spencer’s 1960 novella. It’s short, sharp, and even more ambiguous than the film. It gives you a deeper look into Meg’s internal monologue.

- Contrast with the Musical: Watch a recording of the Broadway production (starring Victoria Clark and Kelli O'Hara). Seeing how the same story is told through music highlights the cinematic choices made in 1962.

- Research 1960s Neurodiversity: Look into how "mental retardation" (the term used then) was treated in the mid-century. Understanding the lack of options helps you empathize with Meg’s "criminal" choice to hide the truth.

- Film Location Tour: If you ever find yourself in Florence, visit the Piazza della Signoria. Stand where Clara and Fabrizio met. Seeing the scale of the architecture helps you understand why Meg felt so small and overwhelmed by her secret.

The Light in the Piazza film remains a vital piece of cinema history because it refuses to be simple. It’s a beautiful, sun-drenched nightmare of a choice. It challenges the viewer to stop judging and start wondering what they would do in the same position. It’s not just a movie about a girl in Italy; it’s a movie about the terrifying lengths of a mother's love.