Leonardo da Vinci didn’t write books. He didn't really "finish" things in the way we think of today. Instead, he left behind a chaotic, mirrored, and absolutely massive mess of paper that we now collectively call the leonardo da vinci sketchbook. It’s more of a brain dump than a diary. Imagine a genius with severe ADHD and no access to a delete button. That’s what you’re looking at when you open the Codex Arundel or the Codex Leicester.

Honestly, it’s a bit of a miracle these things even exist. After Leonardo died in 1519, his pupil Francesco Melzi hauled trunks of these papers back to Italy. Then, life happened. The pages were scattered, sold to collectors, cut up by "art lovers," and rebranded. Today, we have about 7,000 pages left, but experts like Martin Kemp estimate that might only be a third of what Leonardo actually produced.

The Messy Reality of the Leonardo da Vinci Sketchbook

If you expect a clean, chronological record of a man’s life, you'll be disappointed. A single page in a leonardo da vinci sketchbook might feature a terrifyingly accurate drawing of a human heart right next to a grocery list or a sketch of a weirdly shaped pomegranate. He wrote from right to left. Mirror writing. Why? Some say he was hiding his secrets from the Church. Others, more practically, point out he was left-handed and didn't want to smudge his ink.

The flow of thought is erratic. He’ll start a mathematical proof about the "squaring of the circle" and then abruptly stop to doodle a water wheel or a joke about a friar. It’s visceral. You can see where he ran out of ink. You can see the stains of water or wax.

The Codex Leicester: The Most Famous 72 Pages

You’ve probably heard of this one because Bill Gates bought it in 1994 for over $30 million. It’s the only major leonardo da vinci sketchbook held in a private collection. It isn't full of flying machines. It’s mostly Leonardo arguing with himself about water. He was obsessed with how it moved. He looked at the moon and tried to explain why it reflected sunlight, eventually guessing that it must be covered in water (he was wrong, but his logic about "earthshine" was remarkably close to the truth).

He uses the word "impingement" constantly. He watches rivers hit obstacles. He draws the turbulence. It’s not just art; it’s fluid dynamics four centuries before the term existed. He wasn't just drawing what he saw; he was trying to figure out the rules of the world.

💡 You might also like: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

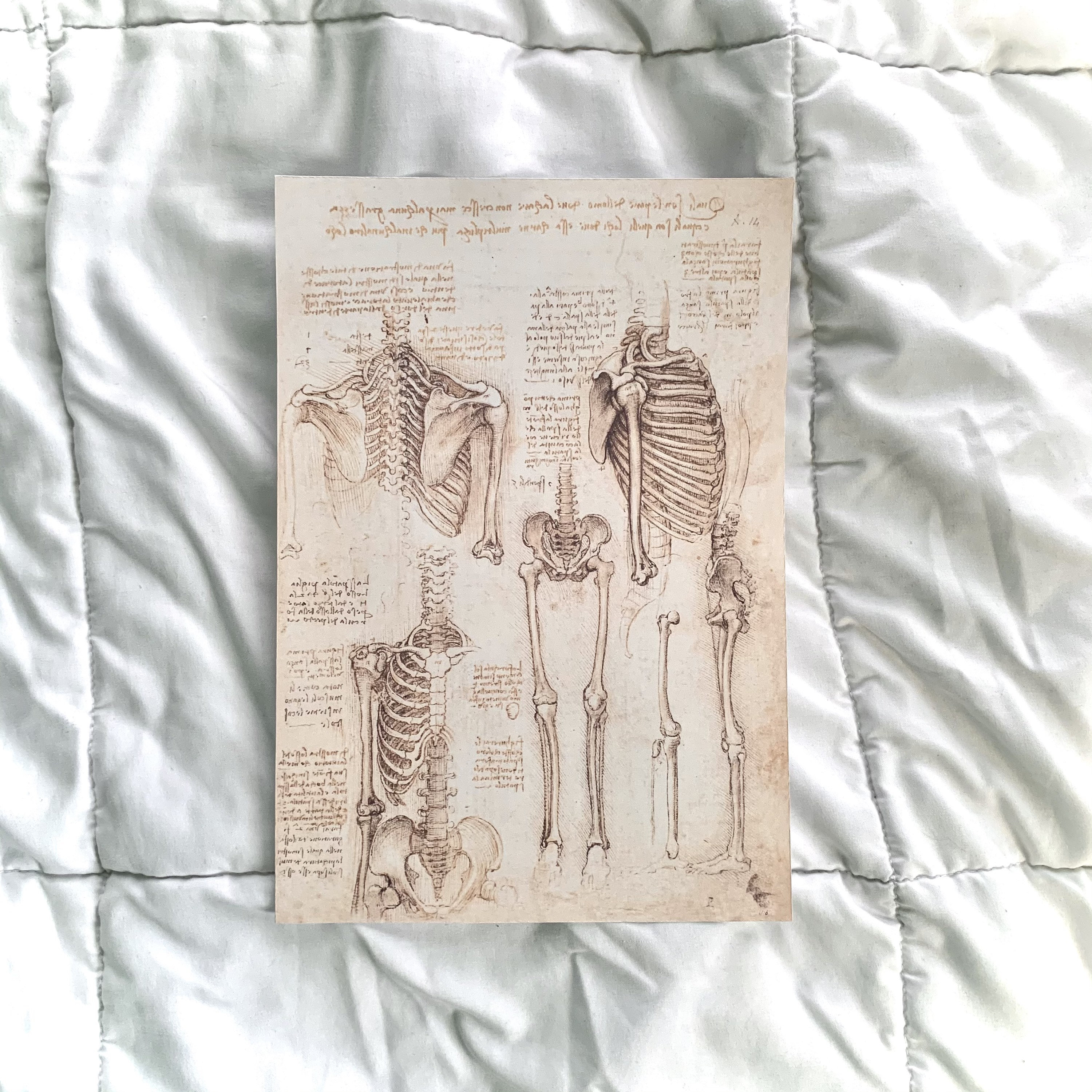

Anatomy and the Architecture of Death

In the early 1500s, Leonardo got access to the morgue at the Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence. This changed everything. His leonardo da vinci sketchbook entries from this period are arguably the most important anatomical records in history. He wasn't just drawing muscles. He was looking for the soul. He literally tried to find where the "senso comune" (common sense) sat in the brain.

He dissected an old man who claimed to be over 100 years old. Leonardo wanted to know why he died so peacefully. Through his sketches, he provided the first known description of coronary vascular disease. Think about that. While other doctors were still talking about "four humors" and balancing blood with bile, Leonardo was drawing the thickening of arterial walls.

- The Fetus in the Womb: One of his most famous sketches. It’s hauntingly beautiful and scientifically groundbreaking, though he mistakenly gave the human uterus the multiple layers found in a cow's.

- The Shoulder: He drew it from multiple angles, like a 3D CAD model. He realized that to understand movement, you had to see the mechanical levers of the bone.

- The Vitruvian Man: This isn't just a cool poster for a dorm room. It’s a study of the "cosmography of the microcosm." He believed the human body was a map of the entire universe.

Engineering Dreams and Epic Failures

Everyone loves the "tanks" and "helicopters." But let's be real for a second. Most of the war machines in a leonardo da vinci sketchbook were totally impractical. His "aerial screw" (the proto-helicopter) would have been too heavy to lift itself. His tank had gears that would have made the wheels turn in opposite directions, effectively locking it in place.

Was he a bad engineer? No. He was a conceptualist. He was thinking about power. He knew he didn't have the engines to make these things work, so he focused on the geometry of the design. He was obsessed with friction. In the Codex Madrid, he spent pages and pages analyzing ball bearings. We use his basic designs in almost every moving machine today.

Why the Writing is Backwards

It’s the first thing people notice. You need a mirror to read a leonardo da vinci sketchbook. It’s quirky. It’s also a bit of a headache for scholars. There’s no evidence he was trying to be "mysterious." Leonardo was a self-taught man who didn't know Latin well. He called himself an "unlettered man." Writing in reverse was just his natural state. It was his private space where he didn't have to perform for the elites of Milan or Rome.

📖 Related: Album Hopes and Fears: Why We Obsess Over Music That Doesn't Exist Yet

Where to Actually See Them

You can't just walk into a museum and flip through these. They are incredibly fragile. Light kills them. But, thanks to high-res digitization, they’re more accessible than ever.

- The British Library: Holds the Codex Arundel. It’s a collection of papers bound together later, covering everything from optics to the weight of water.

- The Victoria and Albert Museum: Home to the Forster Codices. These are tiny, pocket-sized notebooks. He used to carry them tucked into his belt while walking through the streets of Florence to jot down interesting faces.

- The Royal Collection at Windsor: This is where the "good stuff" is—the anatomical drawings. They belong to the British Royal Family.

- The Institut de France: Holds twelve different manuscripts, often referred to as Manuscripts A through M.

The Myth of the "Lone Genius"

One thing people get wrong about the leonardo da vinci sketchbook is the idea that he did all this in a vacuum. He didn't. He was constantly reading other people's work—or trying to. He had a library. He mentions books by Valturio and Albertus Magnus. He was part of a conversation. His sketches often reflect him trying to prove a contemporary wrong or taking an existing idea and making it ten times better.

He was also a procrastinator. His notebooks are filled with "tell me" prompts. Tell me if anything was ever finished. Tell me how the tongue of a woodpecker works. He was a man who couldn't stop asking "why." This curiosity is what makes the pages feel so alive today. They aren't dead history. They are the sound of a mind working at 200 miles per hour.

Practical Insights from Leonardo’s Habits

If you want to apply the "Leonardo method" to your own life, it’s not about being a master painter. It’s about the observation.

Carry a "Forster" notebook. Leonardo didn't wait for inspiration. He caught it in the moment. He’d see a weird bird wing and draw it immediately. Digital notes are fine, but there's a cognitive link between the hand and the brain that Leonardo mastered.

👉 See also: The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads: Why This Live Album Still Beats the Studio Records

Combine disciplines. Don't just be a "tech guy" or a "writer." Leonardo’s best ideas came from cross-pollination. He used his knowledge of water flow to understand how blood moved through heart valves. He used his knowledge of light (optics) to make the Mona Lisa’s eyes follow you.

Embrace the draft. Most of the leonardo da vinci sketchbook is a mess of crossed-out lines and corrected mistakes. He wasn't afraid to be wrong on paper. That's where the growth happened.

Next Steps for Deep Exploration

Start by visiting the British Library's "Turning the Pages" digital archive. It’s free. You can zoom in on the Codex Arundel and see the texture of the paper. Next, look for the "Codex Atlanticus" online gallery maintained by the Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana. It is the largest collection of his drawings, covering everything from weaponry to botany. Finally, if you're ever in London or Paris, check the temporary exhibition schedules; these notebooks are rotated frequently to prevent fading, and seeing the actual ink on 500-year-old paper is a life-changing experience for anyone interested in the limits of human potential.