If you’ve ever looked at a side-profile X-ray of a human head and felt like you were staring at a chaotic mess of shadows and white lines, you aren't alone. It’s a lot. Honestly, the lateral view of cranium is probably the most intimidating perspective for first-year med students and even some seasoned clinicians to wrap their heads around. But here’s the thing: it is the "gold standard" for a reason. While a frontal view (PA or AP) shows you symmetry, the lateral view gives you depth. It lets you see how the brain bucket actually sits on the spine.

It’s messy. It’s crowded. But once you know how to squint, it tells a story.

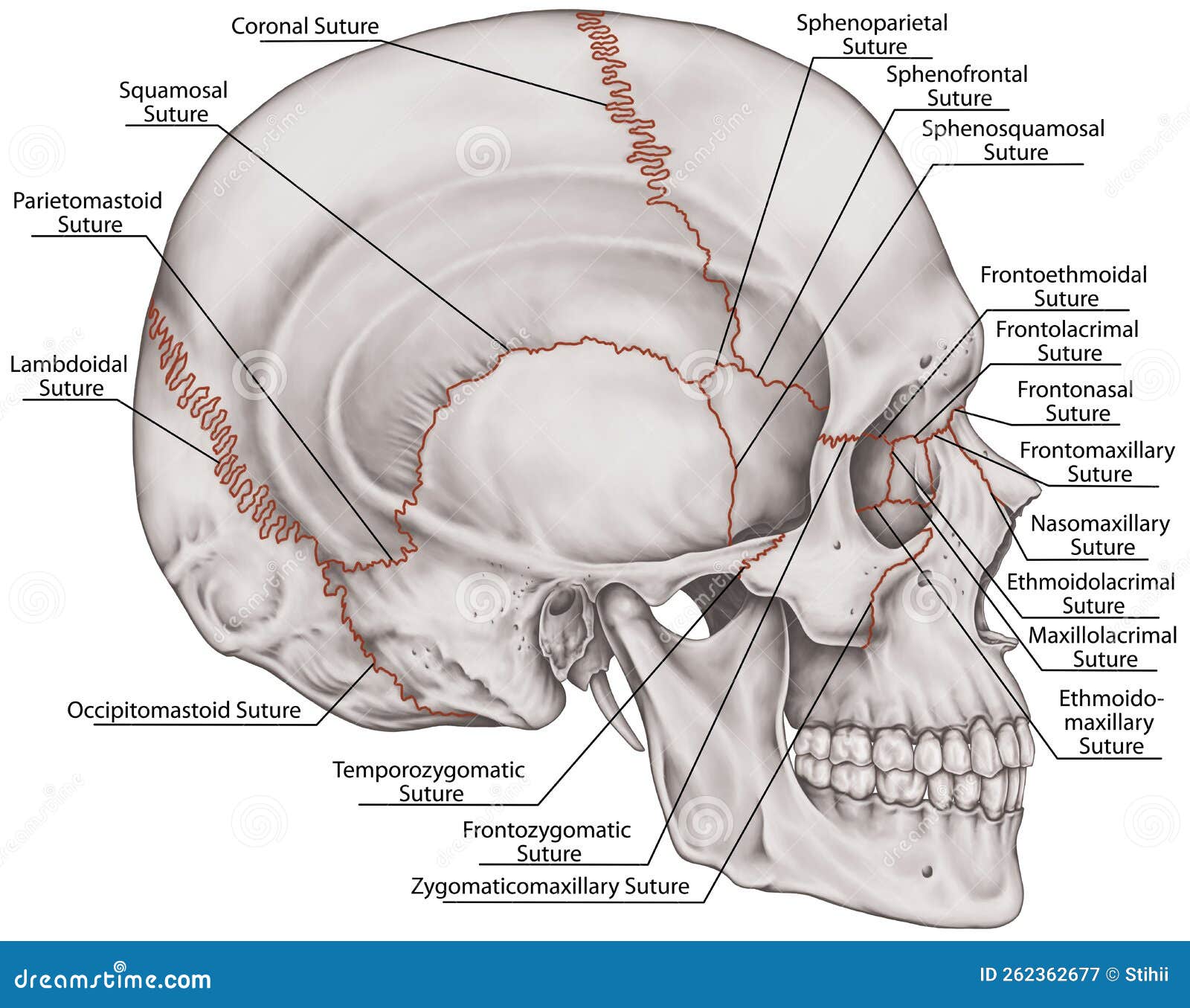

Think about the skull for a second. It isn't just one solid bone; it's a jigsaw puzzle of 22 bones held together by fibrous joints called sutures. When you look at it from the side, you’re seeing the overlap of the parietal, temporal, and sphenoid bones, all competing for space. You’re also seeing the sella turcica—that little "Turkish saddle" where the pituitary gland hangs out. If that looks weird on a scan, something is usually very wrong.

Anatomy of the Lateral View of Cranium: What You’re Actually Looking At

When a radiologist or an anatomist looks at a lateral view of cranium, they aren't just looking for cracks. They’re checking the "lines." Specifically, they’re looking at the relationship between the face and the braincase.

You’ve got the coronal suture running down from the top, separating the frontal bone from the parietal bones. Then there’s the lambdoid suture at the back, which looks like a jagged mountain range. But the real star of the show from this angle is the pterion. This is a tiny, H-shaped junction where the frontal, parietal, temporal, and sphenoid bones all meet. It’s thin. It’s fragile. And right underneath it sits the middle meningeal artery. This is why a punch to the temple or a side-impact fall is so dangerous. If the pterion breaks, that artery can tear, leading to an epidural hematoma. Basically, it’s the "kill switch" of the human skull.

👉 See also: What Does DM Mean in a Cough Syrup: The Truth About Dextromethorphan

The base of the skull in this view is equally fascinating. You can see the clivus, a slanting bone that supports the brainstem. If the angle of the clivus is off, it can indicate conditions like basilar invagination, where the spine is essentially pushing up into the brain. It's wild how much geometry matters in biology.

The Weird Landmarks Nobody Mentions

Most textbooks talk about the big bones, but the small stuff on a lateral scan is what actually helps with diagnosis.

- The external auditory meatus (your ear hole).

- The mastoid process (that bump behind your ear).

- The clinoid processes (the little "horns" protecting the pituitary).

Take the mastoid process. In kids, it’s barely there. As we grow, it becomes "pneumatized," meaning it fills with air cells. If a lateral X-ray shows those cells are cloudy or white instead of black, that’s a massive red flag for mastoiditis, which used to be a leading cause of death in children before antibiotics.

Why Clinicians Care About This Specific Angle

You might wonder why we don't just use CT scans for everything. CTs are great, sure. They give us slices. But a plain lateral view of cranium is still the fastest way to check for a "step-off" fracture or a "ping-pong" fracture in an infant. It’s also the primary tool for cephalometric analysis in orthodontics. Orthodontists use this view to measure the "SNA" and "SNB" angles—fancy talk for seeing if your jaw is too far forward or back relative to your skull.

✨ Don't miss: Creatine Explained: What Most People Get Wrong About the World's Most Popular Supplement

There’s also the "Sella Turcica" check. This little bony pocket is incredibly consistent in size. If a doctor sees it looking enlarged or "eroded" on a lateral film, they immediately suspect a pituitary tumor. It’s like a built-in alarm system.

The Sphenoid Bone: The Bat Inside Your Head

If you could pull the bones apart, the sphenoid would look like a butterfly or a bat with its wings spread. In a lateral view of cranium, you only see a portion of it—the "greater wing." But this bone is the "keystone." It touches almost every other bone in the cranium.

When people have chronic sinus issues, the lateral view shows the sphenoid sinus sitting right under the sella turcica. If there’s fluid there, you’ll see a "level" on the film, kind of like water in a glass. It’s one of the few places in the body where you can literally see gravity working on an X-ray.

Common Misconceptions and Shadows

One thing that trips people up is "overlapping shadows." Because the skull is a 3D object flattened into a 2D image, the left and right sides are superimposed.

🔗 Read more: Blackhead Removal Tools: What You’re Probably Doing Wrong and How to Fix It

Sometimes, a blood vessel groove on the inside of the skull can look like a fracture. Or, the "parietal thinning" that happens in some elderly people can look like a hole. You have to be careful. A real fracture usually has sharp, jagged edges and doesn't follow the predictable path of a suture or a vein.

Also, don't get me started on the "Pinna shadow." Sometimes the external ear itself creates a faint shadow on the film that makes it look like there’s a mass in the brain. It’s just skin and cartilage, but it’s fooled more than a few interns.

Clinical Pearls for Identifying Issues

- The Bone Texture: Look for "salt and pepper" appearance. This can be a sign of hyperparathyroidism.

- The Inner Table vs. Outer Table: The skull has two layers of hard bone with a spongy layer (diploe) in between. If the space between them is widening, it could be a sign of something like sickle cell anemia (the "hair-on-end" appearance).

- The Base of Skull: If the base looks like it's "melting" or flattening, we call that platybasia.

Making Sense of the Chaos

Understanding the lateral view of cranium isn't about memorizing every tiny bump. It’s about recognizing the silhouette. You want to see smooth curves. You want to see clear, dark pockets of air in the sinuses. You want to see the "calvaria" (the skull cap) having a consistent thickness.

If you're looking at your own scans or studying for a board exam, focus on the "Lines of Rogers." These are specific alignment markers that ensure the skull is sitting correctly on the first cervical vertebra (the Atlas). If those lines don't line up, the patient might have a life-threatening instability.

Actionable Insights for Interpreting Cranial Anatomy

If you are a student or a curious patient, keep these practical points in mind when viewing a lateral image:

- Trace the "S" Curve: Look at the front of the face and trace the line from the forehead down to the chin. Any sharp "steps" or breaks in that smooth flow usually indicate a fracture.

- Check the Air: Your sinuses (frontal and sphenoid) should be black. If they are grey or white, there's fluid, blood, or a tumor blocking the air.

- The Pituitary Pocket: Look for the sella turcica in the middle of the skull base. It should look like a neat little "U" shape. If it looks flattened or blown out, it's a major clinical finding.

- Verify the Sutures: In adults, sutures should be faint. If they are wide open (diastatic), it suggests high intracranial pressure. In babies, they should be open; if they are fused too early (craniosynostosis), the brain won't have room to grow.

The skull is a masterpiece of engineering. The side view is the best way to appreciate how the face, the jaw, and the brain all integrate into one functional unit. Next time you see one, don't just see a skeleton—see the architecture that keeps you, you.