Townes Van Zandt was never going to be a superstar. He knew it. His manager, Kevin Eggers, probably knew it too, even if he kept pushing for that one crossover hit that would finally put Townes in the same conversation as Kris Kristofferson or Guy Clark in the eyes of the general public. In 1972, they released The Late Great Townes Van Zandt, an album with a title that felt like a grim joke, considering Townes was very much alive and only twenty-eight years old at the time. It’s a record that smells like stale cigarettes and cheap bourbon, yet it contains some of the most crystalline, devastating poetry ever committed to tape.

If you’re looking for high-gloss Nashville production, you’re in the wrong place. This album is raw. It’s weird. It’s arguably the definitive statement from a man who spent his life drifting between Houston dive bars and Nashville hotel rooms, writing songs that felt like they had existed for a hundred years before he found them. Honestly, the "Late Great" moniker wasn't just a prank; it was a nod to the fact that Townes was already a ghost in his own life, a guy who lived so hard and so fast that people were already eulogizing him while he was sitting right in front of them.

The Story Behind the Morbid Title

People always ask about the name. Was it a marketing ploy? A premonition? Mostly, it was just Townes being Townes. He had a dark, twisted sense of humor that often shielded a deep-seated melancholy. By the time 1972 rolled around, he had already released five albums in five years. He was prolific, but he was also becoming a legend in the "songwriter's songwriter" sense, which is usually code for "brilliant but broke."

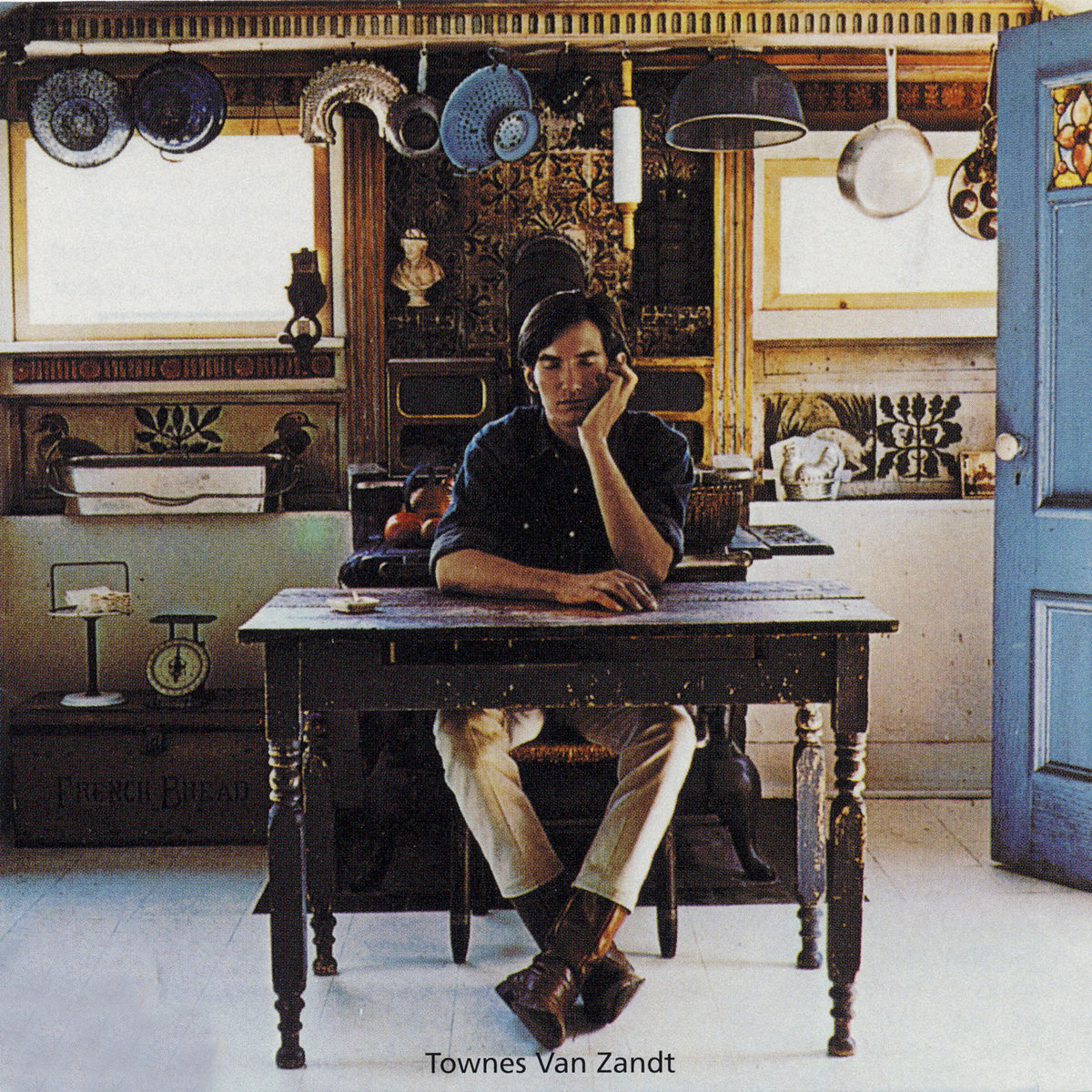

Eggers and the team at Poppy Records wanted something that would grab attention. They went with a cover that looked like a funeral program. You see Townes sitting there, looking gaunt and ethereal, surrounded by a black border. It was a bold move. Some critics thought it was pretentious. Others realized it was a perfect encapsulation of the man’s persona. He was a guy who walked the line between the living and the dead every single day, fueled by a heavy intake of vodka and whatever else was within arm's reach.

The sessions for The Late Great Townes Van Zandt took place at Jack Clement’s Recording Studios in Nashville. Cowboy Jack Clement was a legend in his own right, having worked with Elvis and Johnny Cash, and he brought a certain "weird Nashville" energy to the tracks. He understood that you couldn't polish Townes too much or you'd lose the dirt under the fingernails. You hear that in the arrangements—there’s a bit of strings here and there, maybe a flute that feels a little out of place, but at the center of it all is that steady, thumb-thumping guitar style and a voice that sounds like it’s being pulled out of a well.

Pancho and Lefty: The Song That Changed Everything (Sorta)

You can't talk about this album without talking about "Pancho and Lefty." It’s the centerpiece. It’s the song that eventually made Townes a lot of money when Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard covered it a decade later, but the version on The Late Great Townes Van Zandt is the definitive one.

Townes famously said he didn't really know what the song was about. He claimed it just came to him while he was holed up in a hotel room outside of Denton, Texas. Is it about two outlaws? Is it about the betrayal of a friend? Is it a metaphor for the music business? It doesn't matter. The lyrics are haunting. When he sings, "All the Federales say they could have had him any day, they only let him go so long out of kindness, I suppose," you feel the weight of a myth being built in real-time.

- The song lacks a traditional chorus, which was a huge risk for a "single."

- It relies on narrative storytelling that shifts perspective between the two protagonists.

- The instrumentation is sparse, focusing on the interplay between the acoustic guitar and a mournful harmonica.

Most people don't realize that "Pancho and Lefty" wasn't an immediate hit. Far from it. It lived in the underground for years, passed around like a secret handshake among folk singers. Emmylou Harris was one of the first to really champion it, but it took the 1983 Willie and Merle version to turn it into a standard. Even then, the original recording on this album remains the most gut-wrenching. There's a fragility in Townes' delivery that Willie—as great as he is—just couldn't replicate. Willie sounds like a storyteller; Townes sounds like the guy who was actually there, watching Pancho die in the cold.

🔗 Read more: Did Mac Miller Like Donald Trump? What Really Happened Between the Rapper and the President

Beyond the Hits: "If I Needed You" and the Deep Cuts

While "Pancho and Lefty" gets all the glory, the rest of The Late Great Townes Van Zandt is just as vital. Take "If I Needed You." It’s a love song, but it’s not a happy one. It’s a song about desperation and the hope that someone will be there to catch you when you inevitably fall. It’s been covered by everyone from Andrew Bird to Mumford & Sons, but again, the version here is the blueprint.

Then you have the covers. Townes didn't just write masterpieces; he curated them. His version of Hank Williams' "Honky Tonkin'" is a trip. It’s faster, more frantic, and highlights Townes' love for the blues and old-school country. He also tackles "Fraulein," a song made famous by Bobby Helms. These covers act as a bridge, showing that Townes wasn't just some avant-garde folkie; he was deeply rooted in the traditions of the South.

But the real "hidden" gem is "Sad Cinderella." It’s one of his more surrealist pieces. The imagery is dense and confusing, bordering on Dylan-esque but with a Texas grit that Dylan never quite possessed.

"And your mother, she is seeking for the lost and found / And your father, he is sleeping on the cold, cold ground."

That’s pure Townes. He had this way of taking fairy tale tropes and dragging them through the mud until they felt real. He wasn't interested in "happily ever after." He was interested in the "after," where the characters are broke, tired, and looking for a drink.

Why This Album Still Ranks as a Masterpiece

It’s easy to look back and romanticize the "tortured artist" trope. We do it with Elliott Smith, we do it with Nick Drake, and we certainly do it with Townes. But The Late Great Townes Van Zandt isn't great because the guy was a mess. It's great because the songwriting is mathematically perfect while remaining emotionally messy.

He had this incredible ability to use simple language to describe complex feelings. He didn't use big words. He used words like "dust," "wind," "gold," and "shame." He understood the rhythm of the English language in a way that few poets do. If you strip away the music, the lyrics stand up on their own as literature.

💡 You might also like: Despicable Me 2 Edith: Why the Middle Child is Secretly the Best Part of the Movie

There's also the production by Kevin Eggers and Jack Clement. By 1972, the "Nashville Sound" was becoming increasingly slick and over-produced. This album pushed back against that. It sounds "roomy." You can hear the space between the notes. There’s a certain intimacy to it, like you’re sitting in the corner of the studio while they’re tracking. That's a hard thing to capture, and it's why the record hasn't dated. It doesn't sound like 1972; it just sounds like Townes.

The Tragic Legacy of Poppy Records

Poppy Records was a strange label. It was small, independent, and run by people who genuinely cared about art, which is usually a recipe for financial disaster. They gave Townes the freedom to make exactly the records he wanted to make, but they lacked the muscle to get him on the radio.

Because of the label's eventual collapse and the messy legal battles over Townes' catalog that followed for decades, The Late Great Townes Van Zandt was actually hard to find for a long time. It became a cult item. You had to know a guy who had a copy. This scarcity only added to the myth. By the time it was widely reissued on CD and later on streaming platforms, the "Late Great" title had become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Townes died on New Year's Day in 1997, his body finally giving out after years of abuse. He was 52.

Listening to the Album Today: A Modern Perspective

If you’re coming to this album for the first time in the 2020s, it might feel a bit jarring. We’re used to everything being pitch-corrected and time-aligned. Townes’ voice wavers. He goes slightly sharp on some notes and flat on others. His timing isn't always perfect.

But that's the point.

In a world of AI-generated music and hyper-processed pop, The Late Great Townes Van Zandt feels like a slap in the face. It’s human. It’s flawed. It’s a reminder that great art doesn't have to be "good" in a technical sense; it just has to be true. When you listen to "No Lonesome Tune," you're not listening to a singer perform a song; you're listening to a man try to convince himself that he’s going to be okay.

Essential Tracklist Breakdown

- Pancho and Lefty - The epic ballad that defined his career.

- Silver Ships of Anduin - A rare foray into Tolkien-inspired imagery, showing his range.

- Heavenly Houseboat Blues - A fast-paced, quirky track that highlights his fingerpicking skills.

- Fraulein - A tender cover that showcases his respect for country roots.

- Don't Let the Sunshine Fool You - A Guy Clark cover that Townes arguably owns.

How to Properly Experience This Record

Don't shuffle it. Please. This isn't a "background music" album. To really get what Townes was doing, you need to sit with it.

📖 Related: Death Wish II: Why This Sleazy Sequel Still Triggers People Today

First, get the best audio quality you can find. If you can track down a vinyl pressing—even a reissue—do it. The analog warmth suits these songs. Turn the lights down. Get a drink if that's your thing. Listen to the way his voice changes from the beginning of the record to the end. There’s a trajectory here.

Second, look up the lyrics. Not because they’re hard to hear, but because there are layers of meaning you’ll miss on the first pass. The way he uses internal rhyme schemes in "Pancho and Lefty" is a masterclass in songwriting.

Finally, recognize that this album is a part of a larger story. It sits in the middle of a run of albums—Our Mother the Mountain, Townes Van Zandt, and High, Low and In Between—that represent one of the greatest streaks in American music history.

Moving Forward With Townes' Catalog

If this album clicks for you, your next step is to dive into the live recordings. While the studio stuff is great, Townes was a different beast on stage. Live at the Old Quarter, Houston, Texas is often cited as his best overall release, and for good reason. It features many of the songs from The Late Great Townes Van Zandt, but stripped down to just him and his guitar, with the sound of beer bottles clinking in the background.

You should also check out the documentary Be Here to Love Me. It provides the necessary context for the madness that surrounded the recording of these songs. It’s a heavy watch, but it makes the music hit even harder.

Understand that Townes Van Zandt wasn't a "country" singer or a "folk" singer in the traditional sense. He was a bluesman who happened to grow up in a wealthy family in Fort Worth. He spent his life trying to outrun his demons, and for a brief moment in 1972, he managed to trap them on tape. That’s what you’re hearing when you play this record. It’s not just music; it’s a document of a man's soul, laid bare for anyone brave enough to listen.

Start by listening to the original "Pancho and Lefty" and compare it to the 1983 cover. Notice the difference in the "white light" and the "desert's grey." Once you hear the sadness in the original, you can't unhear it. From there, move to "If I Needed You" and let the rest of the album wash over you. It’s a journey worth taking, even if it leaves you a little bit broken by the time the needle hits the run-out groove.