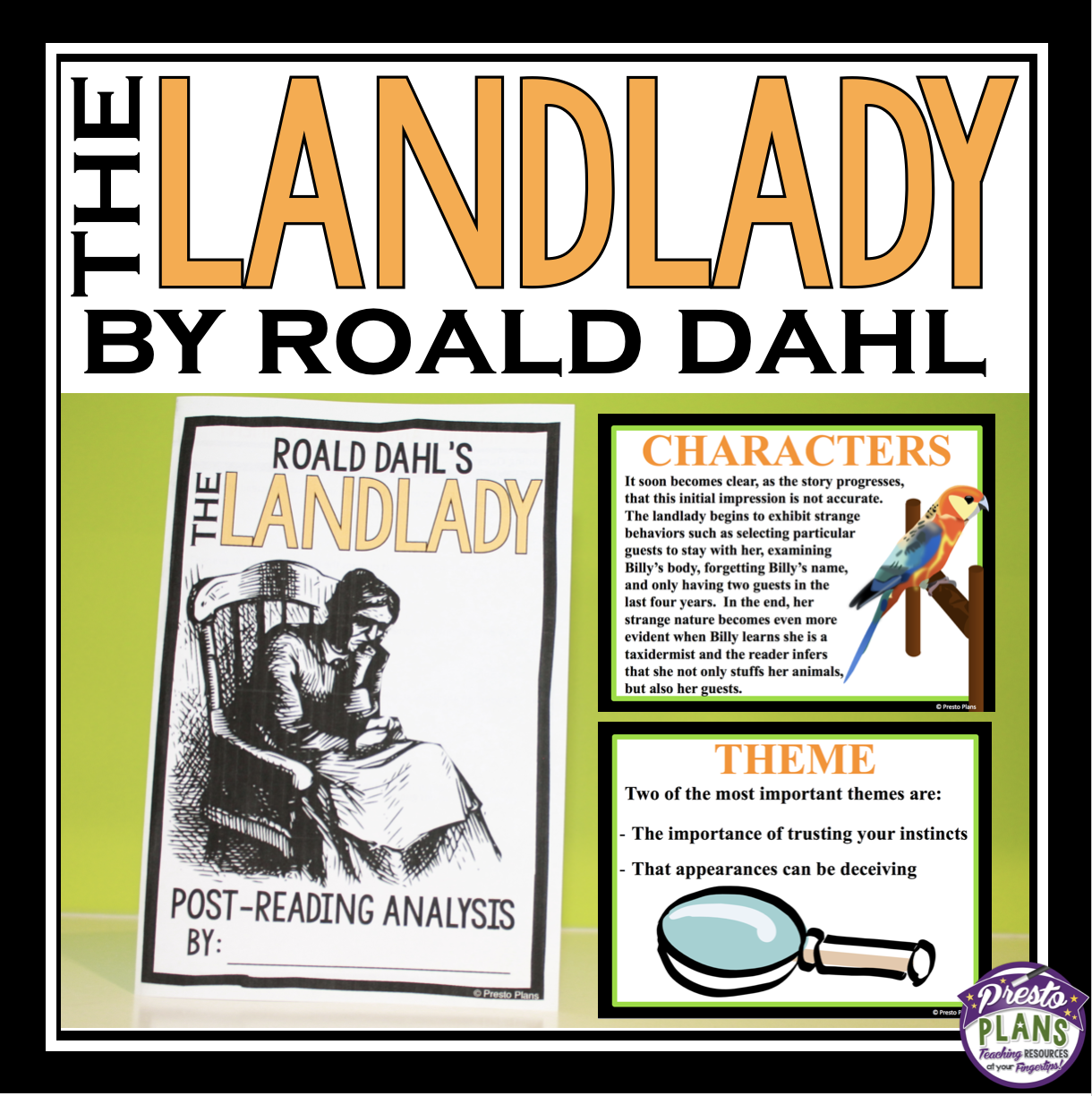

Roald Dahl had a gift for making the mundane feel absolutely terrifying. You probably know him for giant peaches or chocolate factories, but the man had a dark side that would make Stephen King blink twice. The Landlady by Roald Dahl is basically the gold standard for that "something is very wrong here" feeling. It’s a short story, sure. You can read it in ten minutes. But those ten minutes will stick in your brain for about ten years.

Honestly, it’s a masterclass in dramatic irony. We see the trap. Billy Weaver, our protagonist, just sees a cheap room and a nice lady.

The Setup That Tricked a Generation of Readers

Billy is seventeen. He’s "brisk." That’s the word Dahl uses. He’s trying to be a successful businessman, wearing a new navy blue overcoat and feeling like a real adult. He arrives in Bath, England, on a cold evening, looking for a place to stay. He’s told to try the Bell and Dragon pub, but on his way, he gets distracted by a window.

Inside a parlor, he sees a fire burning. There’s a dog curled up by the hearth. A parrot in a cage. It looks cozy. It looks safe. It looks like exactly the kind of place a young guy on a budget would want to crash.

Then he sees the sign: BED AND BREAKFAST.

He’s about to walk away, but the sign catches his eye like a magnet. Dahl describes it as a hypnotic force. Before he even finishes ringing the bell, the door flies open. That’s the first red flag. You don't just open a door that fast unless you were standing right behind it, waiting. Watching.

The woman who answers is "terribly nice." She’s middle-aged, has a round pink face, and gentle blue eyes. She looks like someone’s favorite aunt. But she’s also a bit dotty. She offers him a room for a price that is way too low. In the real world, if a deal seems too good to be true, you’re usually the product. Billy doesn't know that yet.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Landlady's "Guests"

When Billy goes to sign the guest book, he notices something weird. There are only two other names in the book: Christopher Mulholland and Gregory Temple.

Here is where the story gets really dark. Billy swears he’s heard those names before. He thinks they might be famous—maybe athletes? Or explorers? He keeps trying to place them, but the landlady keeps distracting him with tea and talk. She speaks about them in the past tense, but then corrects herself. She says they are still there, on the third floor.

✨ Don't miss: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

The truth is much grimmer.

If you look at the dates, these men checked in years ago. They never checked out. Most readers assume she just killed them, but Dahl drops hints that are far more visceral. As they sit drinking tea, Billy notices a weird smell coming off her. It’s not perfume. It’s not cooking. It’s something "pickled."

It’s the smell of chemicals.

Billy looks at the parrot in the cage. It hasn't moved. He looks at the dog by the fire. It hasn't moved either. He reaches out and touches the dog's fur. It’s hard. It’s cold.

The animals are stuffed.

The landlady reveals, with a terrifyingly casual tone, that she stuffs all her "little pets" when they pass away. Then she looks at Billy and tells him he has "perfect teeth" and that Mr. Mulholland also had no blemishes on his body.

Why This Story Works as a Psychological Thriller

Dahl doesn't show you the murder. He doesn't show you a knife or a taxidermy needle. He doesn't have to. The horror is in the realization that the tea Billy is drinking tastes "faintly of bitter almonds."

For anyone who skipped chemistry class, bitter almonds is the classic scent of cyanide.

🔗 Read more: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

The landlady isn't just a murderer; she’s a collector. She’s looking for the perfect specimens to keep her company forever. It’s a study in loneliness turned into psychosis. She isn't a monster in the traditional sense. She’s a polite English woman who just happens to preserve her guests.

There’s a specific kind of British horror that relies on politeness. It’s the idea that you can be walking straight into your own grave, but because the person leading you there is offering you tea and a biscuit, you don’t want to be rude and leave. Billy is trapped by his own social conditioning. He doesn't want to offend this "sweet" old lady, even as his instincts are screaming at him that the room is too quiet.

The Lasting Influence of The Landlady by Roald Dahl

This story is a staple in middle school and high school curriculums for a reason. It teaches foreshadowing better than almost any other piece of literature. Every line is a breadcrumb leading to the taxidermy table.

- The "compulsion" Billy feels to stay.

- The speed at which she opens the door.

- The lack of other coats or hats in the hall.

- The names in the register belonging to "missing" people.

- The smell of the Landlady herself.

Modern horror owes a lot to this vibe. You can see echoes of it in movies like Get Out or Misery. The "kindly stranger" trope is one of the most effective ways to build tension because it preys on our desire to trust people.

Real-World Lessons from Billy Weaver’s Mistakes

Look, obviously you aren't likely to be stuffed by a taxidermist in a B&B in Bath. But the story does hit on some very real human psychology. We tend to ignore red flags when they are wrapped in a pleasant package.

If you’re traveling alone, there are actual takeaways here. Trust your gut. If a situation feels "off," it doesn't matter if you’re being rude. Billy stayed because he was "brisk" and polite. He died because he didn't want to hurt an old lady’s feelings.

Also, check the reviews. If the guest book only has two names from three years ago, maybe find a Marriott.

Deepening Your Understanding of Dahl’s Darker Works

If The Landlady by Roald Dahl piqued your interest, you should know this was his bread and butter before he started writing about Oompa Loompas. He had a whole series of stories called Tales of the Unexpected. They all have this same "twist" ending that leaves you feeling a bit sick.

💡 You might also like: The Entire History of You: What Most People Get Wrong About the Grain

Another one to check out is Lamb to the Slaughter. It’s about a woman who kills her husband with a frozen leg of lamb and then feeds the evidence to the police officers investigating the crime. It’s brilliant. It’s dark. It’s classic Dahl.

The man understood that humans are the scariest monsters because we can hide behind a smile and a warm cup of tea.

To truly appreciate the craft here, pay attention to the silence. Dahl uses the quiet of the house to build a sense of claustrophobia. There are no other guests. No traffic outside. Just Billy, the lady, and the stuffed parrot.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Students

If you’re analyzing this story for a class or just because you’re a nerd for short fiction, focus on the sensory details. Dahl uses smell and touch more than sight to convey the horror. The smell of the tea, the smell of the lady, the coldness of the dog’s fur. These are visceral details that bypass the logical brain and go straight to the "flight" response.

For writers, the lesson is simple: don't reveal the monster too early. In fact, never reveal the monster at all. The story ends before Billy dies. We don't see him get stuffed. The horror happens in the reader's imagination, which is always going to be more graphic than anything a writer can put on the page.

Next Steps for Readers:

- Read the original text again: Now that you know about the cyanide, the conversation about the tea is ten times creepier.

- Watch the 1979 TV adaptation: It was part of the Tales of the Unexpected series. It’s dated, sure, but the actress playing the landlady captures that "unsettlingly sweet" vibe perfectly.

- Explore the "Missing Person" context: Research how Dahl used real-life fears of the 1950s—the era of the "stranger danger" beginning to take root in the suburban psyche—to fuel his narratives.

- Compare to "Lamb to the Slaughter": Notice the common theme of domestic items (tea, leg of lamb) being used as weapons. It’s a recurring motif in his adult fiction.

The brilliance of the story is its finality. There’s no escape. Billy has already drunk the tea. The door is locked. The Landlady is just waiting for him to fall asleep so she can get to work.