Most people remember the Sleestaks. Those hissing, slow-moving green lizard men are burned into the collective psyche of anyone who grew up near a TV in the mid-seventies. You probably remember the cheesy foam rocks, too. Or that catchy theme song about a camping trip gone horribly wrong. But if you revisit the Land of the Lost television show today, you’ll find something genuinely shocking. It wasn’t just a kids’ show about dinosaurs. It was actually a complex, high-concept science fiction masterpiece masquerading as Saturday morning fluff.

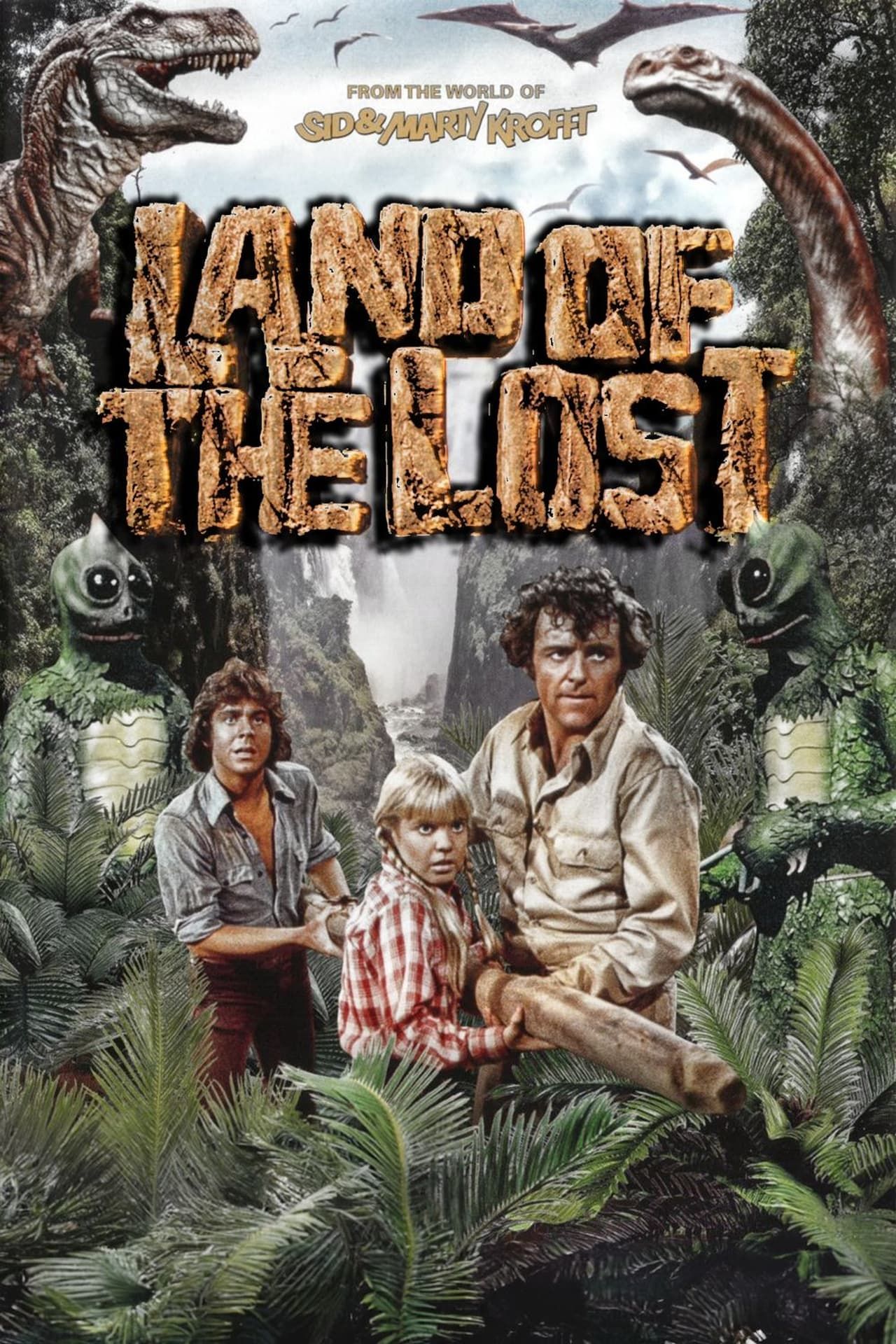

The premise was simple enough. Rick Marshall and his kids, Will and Holly, go down a massive waterfall and end up in a pocket universe. They’re stuck. There are dinosaurs. There are Pakuni (the ape-like creatures). And, of course, the Sleestaks.

But look closer.

The show didn't just play with monster-of-the-week tropes. It tackled non-linear time, interdimensional portals, and the ethics of survival in a closed ecosystem. Honestly, it’s closer to Star Trek or Lost than it is to Barney & Friends. While the production values were definitely "Seventies Krofft style"—meaning lots of bright colors and visible glue—the writing room was stacked with actual sci-fi legends.

The Secret Ingredient: Hard Sci-Fi Writers

How did a show produced by Sid and Marty Krofft, the kings of psychedelic fluff like H.R. Pufnstuf, end up being so brainy?

The answer is David Gerrold.

Gerrold, the man who wrote the legendary Star Trek episode "The Trouble with Tribbles," was the story editor for the first season. He didn't want to make garbage. He brought in heavy hitters from the world of serious literature. We're talking about Larry Niven, a Hugo and Nebula award winner known for Ringworld. We’re talking about Theodore Sturgeon and Ben Bova.

👉 See also: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

These guys didn't write down to children. They wrote about the Pylons.

The Pylons were these mysterious gold structures scattered throughout the jungle. They weren't just background dressing. They were the machinery of the universe. Inside, you had the Matrix tables—basically alien computers that controlled the sun, the weather, and the portals. If the Marshalls messed with them, they didn't just get a zap; they risked collapsing the entire dimension. This was "hard" science fiction. It introduced kids to the idea that the universe is a machine with rules.

Then you had the Pakuni. Most shows would have just made them talk English with a funny accent. Not this one. Victoria Fromkin, a linguistics professor at UCLA, was hired to create a functional, internal language for the Paku. It had its own syntax and vocabulary. When Will and Holly communicated with Cha-Ka, they weren't just making noises. They were learning a constructed language.

It Wasn't Just About Escaping Dinosaurs

Most 1974 television was episodic. You watch it, the status quo is restored, and you tune in next week. The Land of the Lost television show didn't really work that way. It had a weird, haunting sense of continuity.

Take Enik.

Enik is probably the most tragic character in 70s television. He was an Altrusian—a highly evolved, intellectual being who looked like a Sleestak. He came from the past. He realized that his noble, peaceful race would eventually devolve into the mindless, aggressive Sleestaks the Marshalls were hiding from. That is heavy stuff for a seven-year-old eating Froot Loops. Enik was a time traveler stuck in his own race’s nightmare future. He was a mirror for the Marshalls: a refugee trying to get home, trapped in a land that was literally falling apart.

✨ Don't miss: Love Island UK Who Is Still Together: The Reality of Romance After the Villa

The show also experimented with "closed loops." In the episode "The Circle," we find out that the Marshalls are caught in a temporal paradox. The reason they fell into the portal in the first place is because they were already there, signaling themselves. It’s the kind of stuff Christopher Nolan gets paid millions for today. Back then, it was just another Saturday on NBC.

The Low-Budget Aesthetic That Actually Worked

We have to talk about the look.

The special effects were handled by Gene Warren and used a mix of stop-motion animation and chroma key (blue screen). By today’s standards? It looks like a high school play. But there’s a strange, uncanny valley quality to it that makes it feel more alien. The dinosaurs—Grumpy the T-Rex, Big Alice the Allosaurus—had a weight to them because they were physical models moved frame by frame.

The Sleestaks were just tall guys in rubber suits. Big, bug-eyed, slow-moving guys. But the sound design? That persistent, wet hissing? It was terrifying. It turned a budget limitation into a psychological horror element. Because they were so slow, you felt like you could always outrun them, yet they were always there, lurking in the tunnels of the Lost City.

Why Season Three Felt Different

If you talk to a purist, they’ll tell you the show changed after the second season. They’re right.

Spencer Milligan, who played the father, Rick Marshall, left the show in a dispute over merchandising royalties. He was replaced by "Uncle Jack," played by Ron Harper. The tone shifted. The hard sci-fi edges were sanded down. It became more of an adventure show and less of a cosmic mystery.

🔗 Read more: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

That’s usually where the "it’s just a kids' show" reputation comes from. The early seasons, though? They were essentially a serialized novel about the nature of time and space.

Impact and Legacy

The 2009 Will Ferrell movie... well, let's just say it went in a different direction. It turned the property into a broad comedy. While it has its fans, it completely missed the eerie, intellectual dread of the original.

The real legacy of the Land of the Lost television show lives on in shows like Stranger Things or Westworld. It taught a generation of writers that you can have big, weird ideas even if you only have a budget for some spray-painted plywood and a couple of lizard suits.

It also pioneered the "lore" culture. Long before there were wikis for every minor character in a franchise, kids were arguing about how the Pylons worked and what the "Mist of Marsh" actually was. It rewarded you for paying attention.

How to Revisit the Series Today

If you want to dive back in, don't go in expecting Jurassic Park level visuals. You have to adjust your brain to the era.

- Start with Season 1: This is where the world-building is the tightest.

- Watch for the names in the credits: Look for Gerrold and Niven.

- Listen to the Pakuni: Notice how the language evolves as the kids spend more time with Cha-Ka.

- Pay attention to Enik: His episodes are arguably the best written sci-fi of the mid-seventies.

The show is widely available on streaming platforms and physical media. It remains a fascinating time capsule of an era when creators were allowed to be weird, experimental, and surprisingly grim on a Saturday morning.

To truly appreciate the show, look past the rubber suits. Focus on the geometry of the portals. Consider the loneliness of the Altrusians. Realize that for three seasons, the Marshalls weren't just lost in the woods—they were lost in a mathematical anomaly. That’s why it still matters. It was a show that dared to assume kids were smart enough to handle the infinite.

To get the most out of a rewatch, track the "Key" colors used in the Pylon Matrix tables. Each color corresponds to a different physical law—gravity, time, light. Mapping these out as you watch reveals a level of consistency in the writing that was decades ahead of its time. Focus on the episode "The Possession" to see how the show handled character psychological shifts, which was a rare move for children's programming in 1974. Following the internal logic of the Pylons makes the viewing experience a puzzle rather than just a passive activity.