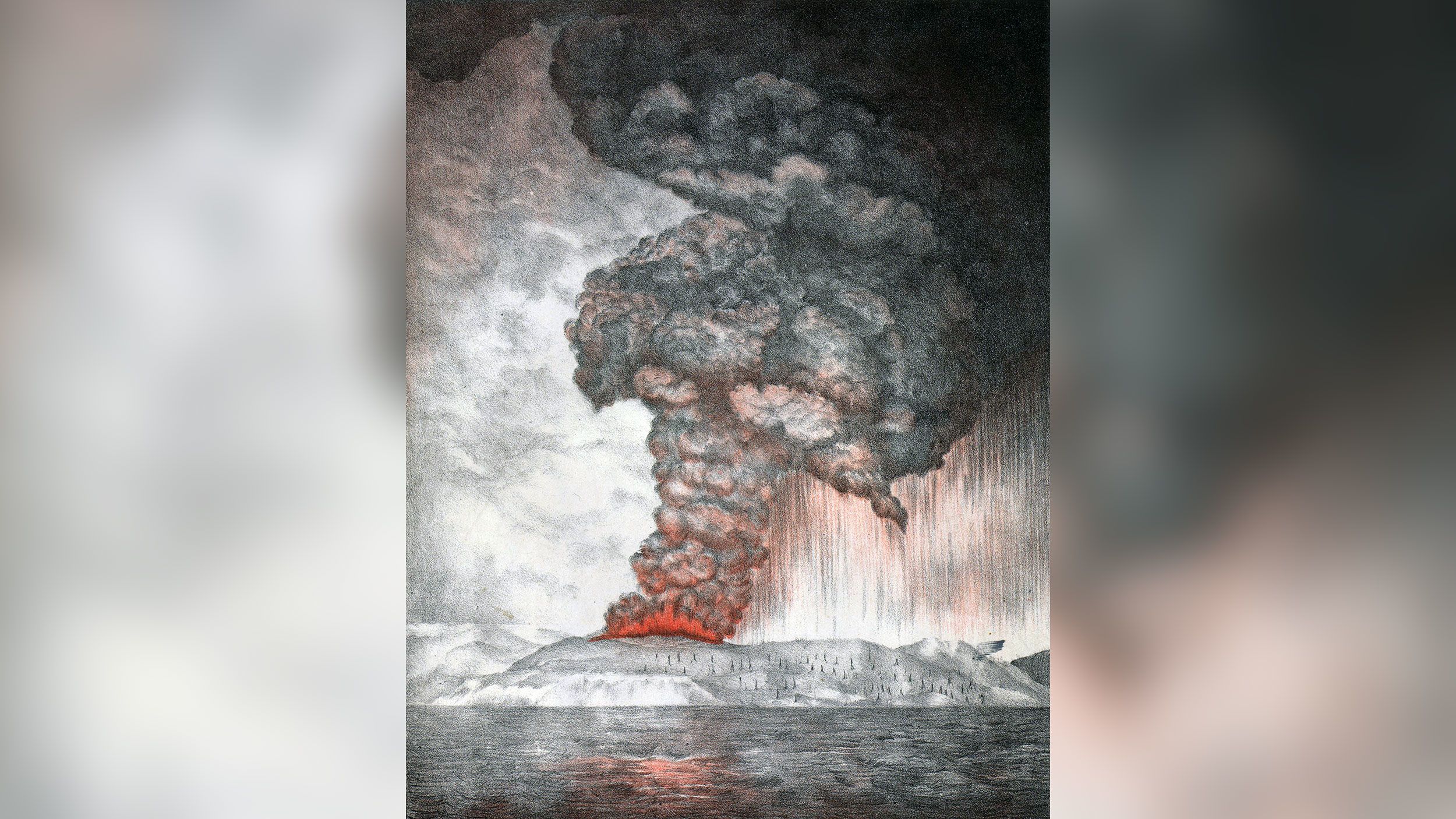

It was loud. Actually, "loud" doesn't even come close to describing it. When the Krakatoa eruption in 1883 reached its terrifying peak on August 27, the sound literally traveled around the world four times. People in Alice Springs, Australia—over 2,000 miles away—heard what they thought were nearby rifle shots. In reality, it was a volcanic island in the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra basically deleting itself from the map.

Nature is usually loud, but this was a different beast entirely. It’s hard to wrap your head around the scale. Most of us think of a big explosion as something like a building demolition or maybe a large firework display. This was equivalent to 200 megatons of TNT. To put that in perspective, the Hiroshima bomb was about 15 kilotons. We’re talking about an event 13,000 times more powerful than the atomic bomb that changed the course of World War II. It changed the weather. It changed the sunset. It even changed how we communicate news.

What actually happened during the Krakatoa eruption in 1883?

Most people assume it was just one big bang. That’s a mistake. The lead-up actually started months earlier in May 1883. The captain of the German warship Elisabeth reported seeing a massive cloud of ash rising above the uninhabited island. For a few months, it was almost a tourist attraction. People from nearby Batavia (modern-day Jakarta) would take excursion steamers out to look at the ash clouds. Honestly, it's kinda wild to think about people picnicking near a ticking time bomb, but they didn't know any better.

By Sunday, August 26, things got real. The island began a series of increasingly violent explosions. Ash reached an altitude of 17 miles. But the real nightmare started Monday morning at 5:30 AM. There were four massive explosions that day. The last one, at 10:02 AM, was the one that tore the island apart.

The physics of the blast

When the magma chamber emptied, the entire island collapsed into the sea. This created a caldera, but more importantly, it triggered massive tsunamis. These weren't your typical waves. We are talking about walls of water 120 feet high. That is roughly the height of a 12-story building rushing toward the coast at hundreds of miles per hour. These waves wiped out 165 villages and towns along the coasts of Java and Sumatra.

The official death toll recorded by the Dutch colonial authorities was 36,417. However, many historians and volcanologists, including experts who have studied the records at the Smithsonian Institution, suspect the number was much higher. Many victims were likely washed out to sea and never counted.

🔗 Read more: The Brutal Reality of the Russian Mail Order Bride Locked in Basement Headlines

The first global media event

One of the most fascinating things about the Krakatoa eruption in 1883 isn't just the geology—it's the technology. This was the first time a natural disaster became "viral" in real-time. The undersea telegraph cables had just been laid. News of the disaster reached London and New York within hours.

Journalists were getting updates as the waves were still hitting the shore. It was the birth of the global news cycle. Before this, a volcano could blow up on the other side of the planet and you wouldn't hear about it for months, if ever. Suddenly, a guy in a London coffee house was reading about a tsunami in the Dutch East Indies over his breakfast.

It created a weird, collective global trauma. It wasn't just local. Everyone was watching.

Weird skies and the "The Scream"

Have you ever looked at Edvard Munch’s famous painting The Scream? You know that blood-red, wavy sky in the background? Scientists like Donald Olson from Texas State University have argued that Munch wasn't just being "artsy." He was likely painting what he actually saw in Norway.

The Krakatoa eruption in 1883 shot so much sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere that it created a global veil of aerosol acid. This didn't just cool the planet; it turned sunsets into psychedelic light shows for years. In New York and London, people called the fire department because they thought the horizon was literally on fire.

💡 You might also like: The Battle of the Chesapeake: Why Washington Should Have Lost

- The global temperature dropped by about 1.2 degrees Celsius in the year following the blast.

- Weather patterns remained chaotic for five years.

- Southern California saw record-breaking rainfall that hasn't been matched since.

Basically, the volcano hacked the Earth's thermostat.

The birth of Anak Krakatau

The original island was gone, but the "Child of Krakatoa" (Anak Krakatau) began emerging from the same spot in 1927. It's still there. It's still active. In fact, in December 2018, a massive chunk of Anak Krakatau slid into the ocean, causing a tsunami that killed over 400 people. It was a grim reminder that the 1883 event isn't just a dusty chapter in a history book. It’s an ongoing geological process.

Volcanologists like Professor Simon Winchester, who wrote extensively on this, point out that the Sunda Strait is one of the most dangerous places on Earth because of the sheer density of the population living right next to these tectonic fault lines.

Why we should still care

Honestly, if an event like the Krakatoa eruption in 1883 happened tomorrow, it would be a total catastrophe for the global economy. The Sunda Strait is a major shipping lane. The atmospheric interference would mess with satellite communications. The tsunamis would hit modern, densely packed cities that didn't exist in the 19th century.

We have better monitoring now, sure. We have sensors and satellite imagery. But the raw power of a VEI-6 (Volcanic Explosivity Index) eruption is something we can't "engineer" our way out of. We just have to get out of the way.

📖 Related: Texas Flash Floods: What Really Happens When a Summer Camp Underwater Becomes the Story

Insights for the future

If you live in a coastal area or near a tectonic boundary, the lessons of 1883 are pretty clear.

- Don't ignore the warning shots. The three months of smaller ash clouds before August were nature's warning. Today, we have seismic monitors that can "hear" magma moving, but people still hesitate to evacuate because of the economic cost.

- Infrastructure is vulnerable. Our global supply chains rely on narrow straits. A repeat of 1883 would bottle up trade between Europe and Asia for months.

- Communication is a double-edged sword. While we get news faster, the spread of misinformation during a disaster can be as deadly as the event itself. Even in 1883, there were rumors of "sea monsters" and "end-of-the-world" prophecies that caused mass panic far from the actual danger zone.

The 1883 event proved that the Earth is a single, interconnected system. What happens in a small strait in Indonesia can change the color of the sky in Norway and the temperature of a farm in Nebraska. We aren't as insulated from nature as our air-conditioned offices make us feel.

To better understand the risks today, you can monitor the Global Volcanism Program hosted by the Smithsonian Institution. They track active peaks like Anak Krakatau in real-time. You should also check the historical tide gauge records if you're interested in how those 1883 waves were measured using mid-19th-century tech—it's surprisingly accurate for the time. Understanding the past is the only way to not be blindsided by the next big one.

---