You’re standing in a dimly lit room in Oslo, staring at a bunch of balsa wood logs lashed together with hemp rope. It looks flimsy. Honestly, it looks like something a group of overly ambitious scouts would build at summer camp and then immediately sink in a lake. But this pile of wood actually crossed 4,300 miles of open Pacific Ocean.

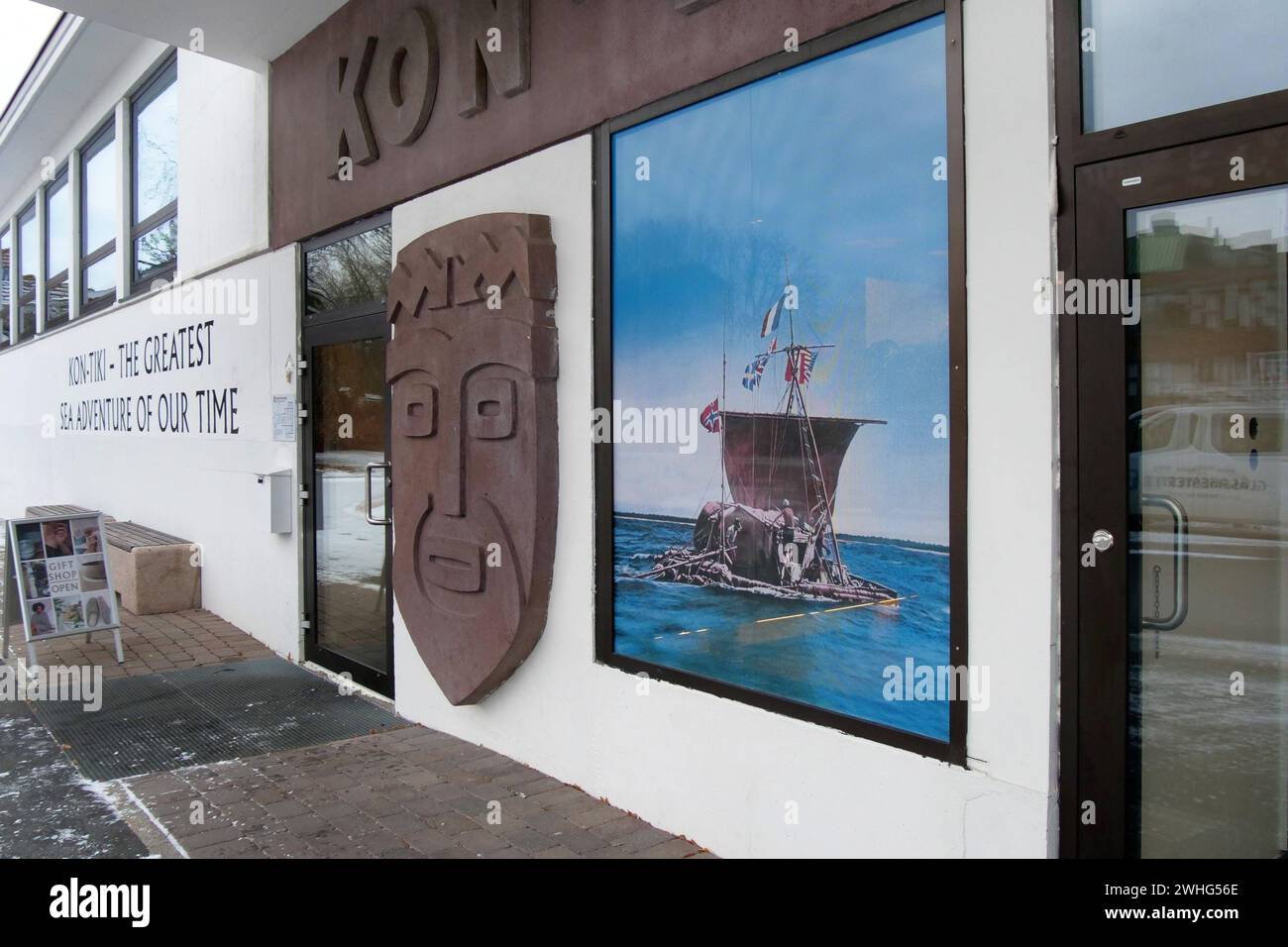

That’s the Kon-Tiki Museum. It’s not just a building full of dusty artifacts; it’s a monument to a guy named Thor Heyerdahl who basically looked at the entire scientific community in 1947 and said, "Watch this."

Most people visiting Norway head straight for the Viking ships or the Munch Museum. Those are great, don't get me wrong. But the Kon-Tiki is different. It’s gritty. It smells like old wood and ambition. It captures a specific moment in history when we still thought the world had massive, unsolvable secrets.

What actually happened on the Kon-Tiki?

In the late 1940s, Thor Heyerdahl had a theory. He was convinced that people from South America could have settled Polynesia in pre-Columbian times. The experts at the time thought he was crazy. They told him it was physically impossible to navigate those distances on a primitive raft.

So, he built one.

He named it Kon-Tiki after an old name for the Inca sun god. He and five other guys (plus a parrot named Lorita) set sail from Callao, Peru, on April 28, 1947. They had no escort boat. They had a radio, sure, but if things went south, no one was coming to save them in time.

The raft was held together by nothing but friction and rope. No nails. No wire. If the ropes snapped, the logs would just drift apart and the crew would be swimming with the sharks. And there were a lot of sharks. If you go to the Kon-Tiki Museum today, you can see the actual raft, and the first thing you notice is how small it is. It’s tiny. You realize these guys were living on top of each other for 101 days.

📖 Related: The Gwen Luxury Hotel Chicago: What Most People Get Wrong About This Art Deco Icon

The stuff they don't tell you in school

People think the trip was a peaceful float. It wasn't. They were constantly surrounded by sea life. At night, bioluminescent creatures would light up the wake of the raft. Sometimes, flying fish would just land on the deck—literally delivering breakfast to their front door.

But then there were the Whale Sharks. Imagine being on a raft that is barely a foot above the waterline and having a fish the size of a bus swim underneath you. Heyerdahl wrote about how the shark's tail would occasionally tap the bottom of the raft.

One of the best things in the museum isn't just the big raft, though. It’s the "underwater" section. They’ve designed the basement level so you can look up at the hull of the Kon-Tiki from below, just like the fish did. You see the massive 30-foot whale shark model lurking there. It’s eerie. It gives you this sudden, sharp realization of how vulnerable they were.

The Ra II and the "Paper" Boat

Most people visit the Kon-Tiki Museum for the balsa raft, but the Ra II is arguably more impressive. After the Pacific crossing, Heyerdahl got obsessed with the idea that ancient Egyptians could have crossed the Atlantic to the Americas using reed boats.

His first attempt, Ra, fell apart. Literally. It dissolved in the water because they didn't follow the traditional construction methods of the Aymara people from Lake Titicaca quite right.

He didn't quit.

👉 See also: What Time in South Korea: Why the Peninsula Stays Nine Hours Ahead

He built Ra II. It’s made of papyrus. Thousands and thousands of reeds bundled together. In 1970, he sailed this "paper" boat from Morocco to Barbados. It worked. When you see Ra II in the museum, it’s remarkably preserved. It looks like a giant, golden cigar. It’s a testament to the fact that "primitive" technology was often way more sophisticated than we give it credit for.

Is Heyerdahl's theory actually true?

Here is where things get complicated. And honestly, this is the most interesting part of the whole story.

Modern DNA testing has mostly debunked the idea that Polynesians originated in South America. Most evidence points toward an Asian origin—people moving through Southeast Asia and into the Pacific.

However!

A 2020 study published in Nature found that there is a tiny bit of Native American DNA in some Polynesian populations, dating back to around 1200 AD. So, while Heyerdahl might have been wrong about the direction of the primary migration, he wasn't totally off base about the contact between the two cultures. They did meet. Someone made the trip.

The Kon-Tiki Museum doesn't shy away from this. They update their exhibits. They acknowledge that science has moved on. It makes the place feel honest. It’s not a shrine to a man who was 101% right; it’s a tribute to the spirit of human curiosity.

✨ Don't miss: Where to Stay in Seoul: What Most People Get Wrong

Surviving your visit (Practical stuff)

If you're going to the Bygdøy peninsula to see this, don't just rush in and out.

- The Ferry: In the summer, take the ferry from Pier 3 behind the Oslo City Hall. It’s a 10-15 minute ride and gives you the best view of the city.

- The Film: They show the original 1950 Oscar-winning documentary in the museum cinema every day at 12:00. Watch it. It’s grainy, black and white, and absolutely gripping. It makes the rafts in the other room come alive.

- The Easter Island Statues: Everyone forgets about the basement. Heyerdahl did a lot of work on Rapa Nui (Easter Island). The museum has a 30-foot tall replica of a Moai, plus a bunch of original carvings.

Why we still care in 2026

We live in a world where everything is mapped. We have GPS. We have Starlink. We have drones that can see every square inch of the ocean.

The Kon-Tiki Museum represents a time when the horizon was actually a mystery. Heyerdahl wasn't a scientist in the traditional sense; he was an experimental archaeologist who used his own life as the experiment.

There's a specific kind of "Norwegian-ness" to the whole thing. It’s that friluftsliv (open-air life) mentality taken to a radical extreme. It’s the idea that you can't understand the world just by reading about it. You have to go out and get wet.

Actionable Advice for Your Trip

- Timing is everything. The museum gets packed with tour groups around 11:00 AM. If you get there right when they open (usually 10:00 AM), you can have the Ra II room to yourself. It’s incredibly quiet and atmospheric.

- Combine it. The Fram Museum (about polar exploration) is literally right next door. Do both. They represent the two extremes of Norwegian exploration: the frozen North and the tropical South.

- Check the "Tiki" pop culture section. The museum has a small area dedicated to how the Kon-Tiki expedition sparked the massive "Tiki culture" craze in the US in the 50s and 60s. It’s a weird, fun look at how serious science turns into kitschy backyard bars.

- Buy the book. The Kon-Tiki Expedition by Heyerdahl is one of the best-selling travel books of all time. Read it on the flight to Oslo. It changes how you look at the logs and the rope when you finally see them in person.

When you walk out of the museum and look over the Oslofjord, you’ll probably feel a bit small. That’s the point. It’s a reminder that the ocean is massive, our history is messy, and sometimes, the crazy guys with the balsa wood rafts are the ones who actually change how we see the world.

To get the most out of your visit, start at the Kon-Tiki Museum early, then walk the coastal path around Bygdøy toward Huk beach. It’s the best way to process the scale of what you just saw while looking out at the same water that eventually leads to the open sea. Don't bother with the overpriced cafeteria inside; head back toward the city center or bring a packed lunch to eat by the water near the ferry pier.