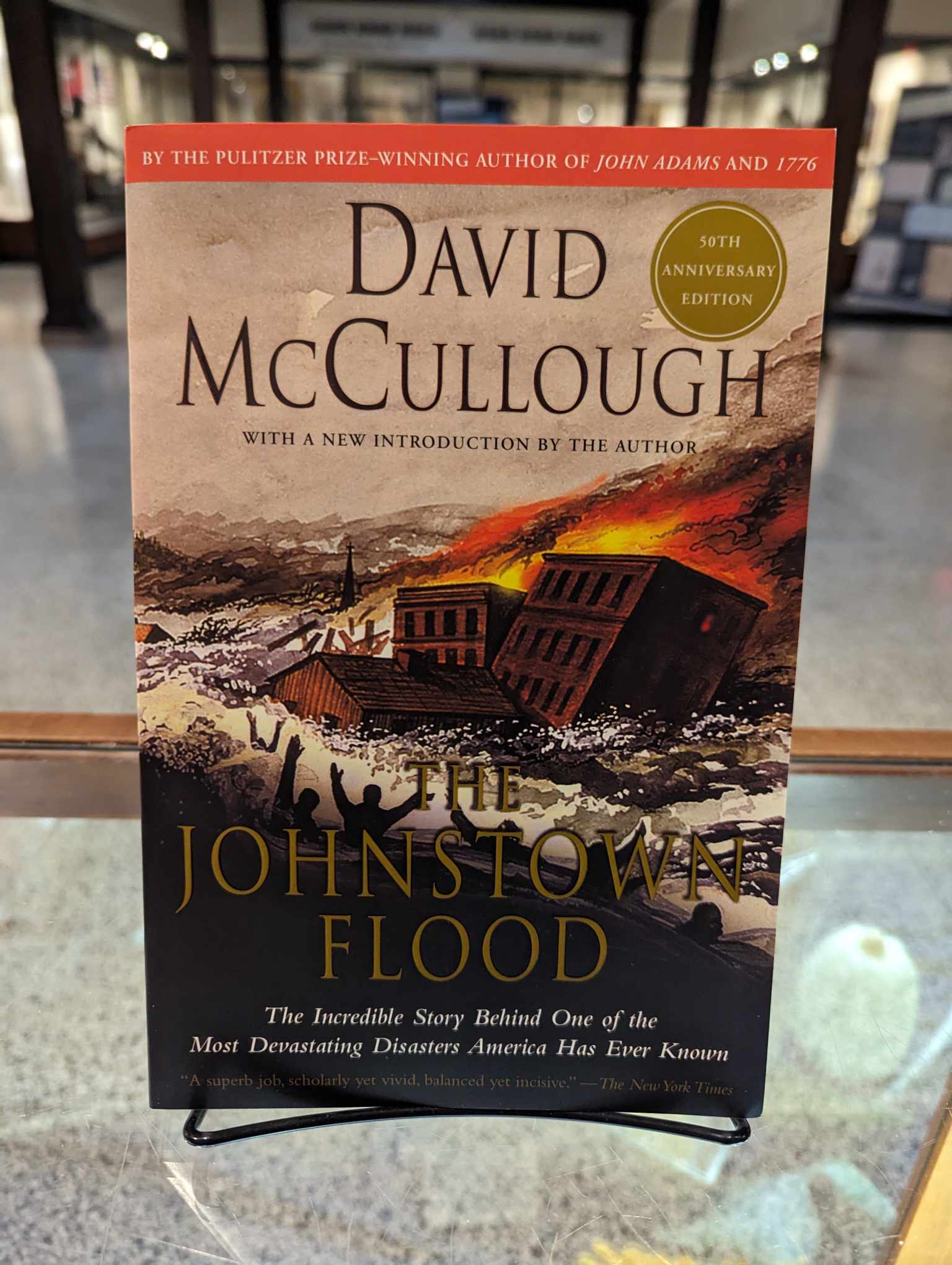

History books usually feel like homework. You know the vibe—dry dates, dusty names, and prose that makes you want to take a nap. But The Johnstown Flood by David McCullough is different. It’s basically a thriller that just happens to be true. Published way back in 1968, it was McCullough's first book, and honestly, he hit it out of the park on his first at-bat. He didn't just write about a dam breaking; he wrote about class warfare, gross negligence, and the terrifying speed of water.

It was a Friday. May 31, 1889.

South Fork Dam, situated high above the industrial city of Johnstown, Pennsylvania, didn't just leak. It vanished. When it gave way, twenty million tons of water—roughly the volume of the Mississippi River for a few minutes—roared down the Little Conemaugh River valley. It wasn't just a wave; it was a rolling mountain of debris, carrying houses, locomotives, and barbed wire. By the time it hit the town, over 2,200 people were dead.

McCullough captures the sheer horror of this better than anyone else. He doesn't just give you the body count. He tells you about the sky turning a weird shade of purple-gray and the sound of the approaching water being described by survivors as a "low growl" or a "roar of a thousand trains."

The South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club: Who Was Really at Fault?

If you want to understand why this book matters, you have to look at the club. This wasn't some local fishing hole. The South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club was an exclusive retreat for the titans of the Gilded Age. We're talking Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, and Andrew Mellon. These guys wanted a summer getaway, so they "repaired" an old, abandoned dam to create Lake Conemaugh.

But here’s the thing. They did a terrible job.

💡 You might also like: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

They lowered the crest of the dam so they could drive carriages across it. They installed fish screens that got clogged with leaves and debris, meaning the spillway couldn't do its job. Basically, they turned a massive earthen wall into a ticking time bomb just so they could have a pretty view and some trout.

McCullough is careful not to turn this into a cartoonish villain story, but the facts speak for themselves. The wealthy club members ignored repeated warnings from engineers like John Parke. On the day of the flood, Parke saw the water rising and tried to warn the town via telegraph, but after years of "the dam is breaking" false alarms, many people in Johnstown just... stayed. They went about their business. They thought it was just another rainy day in the valley.

The Physics of a 40-Foot Wall of Trash

What makes The Johnstown Flood by David McCullough so visceral is his description of the water itself. It wasn't a clean surge. Because the valley was narrow and steep, the water picked up everything in its path.

Think about that for a second.

The "flood" was actually a moving mass of wreckage. It picked up the Gautier Wire Works, which meant miles of razor-sharp barbed wire were churning inside the wave like a giant blender. It picked up locomotives—actual steam engines—and tossed them around like bath toys.

📖 Related: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

The Stone Bridge Massacre

Perhaps the most haunting part of the book is the account of the Stone Bridge. This massive railway bridge stood firm when the water hit. But instead of the water passing through, all the debris—the houses, the train cars, the dead horses, and the living people trapped in the wreckage—piled up against the arches.

Then it caught fire.

Because of the overturned stoves and oil from the wreckage, the massive jam at the bridge became an inferno. People who had survived the initial wave were trapped in the debris pile and burned to death while spectators watched from the banks, unable to reach them. It’s one of the most harrowing scenes in American history, and McCullough writes it with a restrained power that makes it even worse.

Why McCullough’s Research Holds Up

You might wonder if a book from the late sixties is still accurate.

History evolves. New data comes out. But McCullough spent years interviewing the last living survivors. He had access to the private records of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club—records that many of the members probably wished had stayed buried. He used the Transcripts of the American Society of Civil Engineers, which did a deep dive into why the dam failed.

👉 See also: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

The consensus? It wasn't an "act of God," despite what the club's lawyers argued in court. It was a man-made disaster caused by poor engineering and a lack of accountability.

The Aftermath and the Red Cross

This was also the first major test for the American Red Cross. Clara Barton showed up on the scene just days after the disaster. She was in her late 60s, but she stayed for five months, coordinating relief efforts and building "hotels" for the homeless. It was the event that put the Red Cross on the map as a domestic powerhouse.

It’s also where we see the birth of the modern news cycle. Reporters from all over the country flocked to Johnstown. They didn't just report the news; they sensationalized it. Some of the stories they told were completely made up—like the myth of Daniel Periton riding a horse ahead of the wave like Paul Revere. McCullough debunked that. Periton died, but he wasn't a hero on horseback; he was just a guy trying to get out of the way who got caught.

Practical Insights for Today

Reading The Johnstown Flood by David McCullough isn't just about looking at the past. It’s a warning. It’s a study in how infrastructure failure happens when profit and leisure are prioritized over public safety.

If you're going to dive into this book, here are a few things to keep in mind:

- Look at the maps. The topography of the Conemaugh Valley is the reason the death toll was so high. The narrow "V" shape of the valley acted like a funnel, increasing the speed and height of the water.

- Pay attention to the class dynamics. The contrast between the wealthy club members on the mountain and the working-class steelworkers in the valley is the central tension of the book.

- Check the legal fallout. One of the most frustrating parts of the story is that no one was ever held legally responsible. The "Great Flood" resulted in no successful lawsuits against the club members. This led to a major shift in American law toward "strict liability," ensuring that in the future, people would be held responsible for the consequences of their property, even if they didn't intend harm.

If you haven't read it, go find a copy. It’s a masterpiece of narrative non-fiction. It’s short, punchy, and will stay with you long after you put it down.

To get the most out of your study of this event, start by looking up the 1889 Johnstown Flood Museum archives. They have digitized hundreds of photographs that bring McCullough's descriptions to life. Next, if you're ever in Pennsylvania, visit the Johnstown Flood National Memorial. Standing on the remains of the dam breast gives you a terrifying perspective on the scale of the lake that once sat there. Finally, compare this account with McCullough's later work like The Wright Brothers or 1776 to see how his style of focusing on the "human element" of history began right here in the mud of Johnstown.