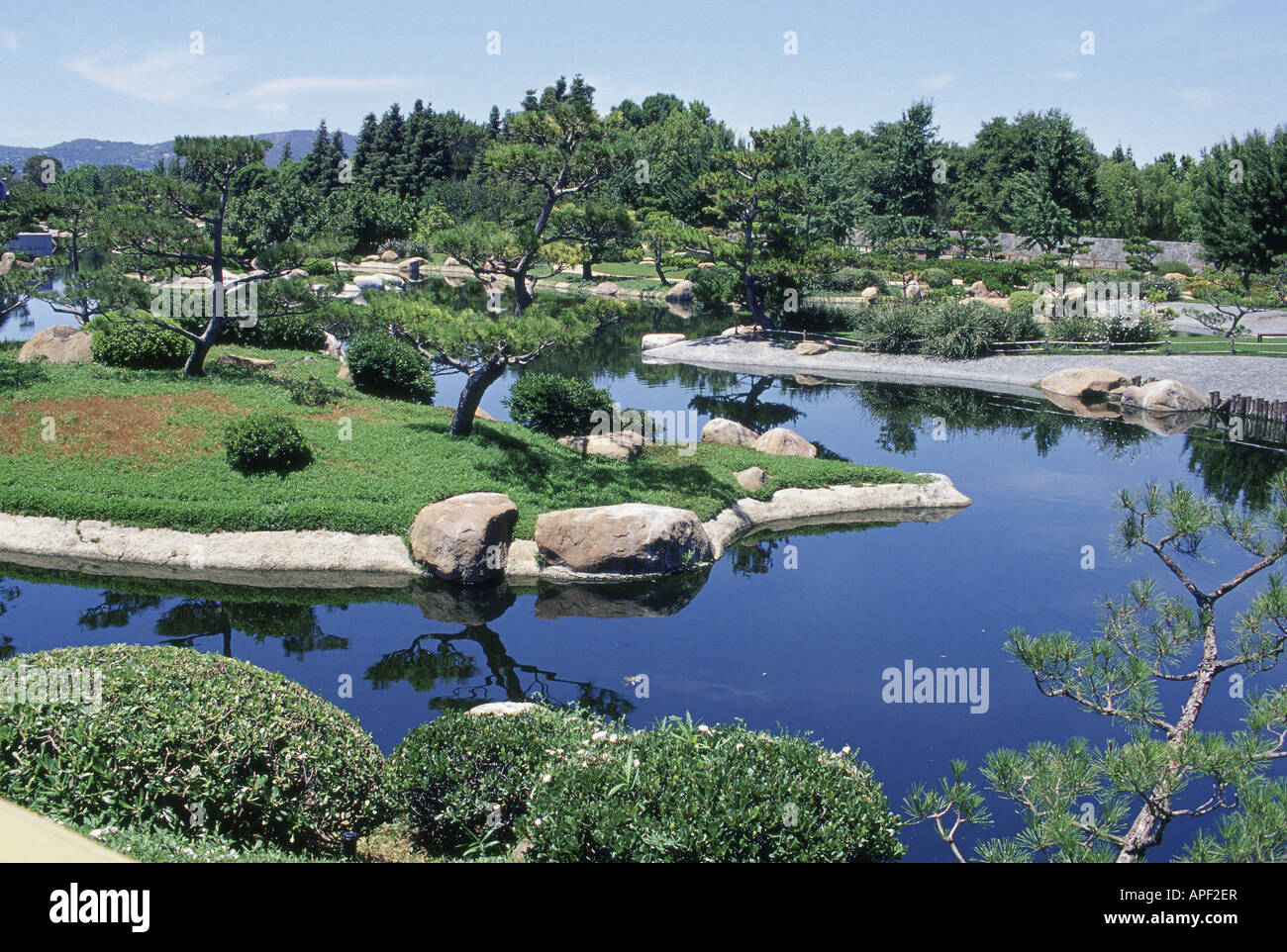

You’re driving down Woodley Avenue in the middle of the San Fernando Valley, surrounded by the usual sprawl of asphalt and the low hum of the 405 freeway, when suddenly, there’s this wall of green. Most people just blink and drive past it. It feels like a glitch in the L.A. grid. But if you pull over, you’ll find The Japanese Garden in Van Nuys, a 6.5-acre oasis that is, frankly, one of the weirdest and most beautiful engineering flexes in Southern California.

It’s officially named SuihoEn, which translates to the "Garden of Water and Fragrance."

Here’s the kicker: the entire place is fed by treated wastewater.

While most of Los Angeles is worrying about drought and xeriscaping, this garden is thriving on what essentially comes from the Tillman Water Reclamation Plant next door. It’s a bit of a mind-bender. You’re standing next to a massive municipal infrastructure project, yet you’re looking at a Zen meditation garden that feels like it was plucked out of 18th-century Japan. Honestly, it shouldn't work as well as it does.

The Dr. Kawana Legacy and the "Wet" Zen Philosophy

The garden was the brainchild of Dr. Koichi Kawana. If you follow landscape architecture, that name carries weight—he’s the same guy who designed botanical gardens in St. Louis and Denver. He was a master of the Chisen-kaiyu-shiki style, or the "stroll garden." The whole point isn't to just sit and look at one thing. You're supposed to move.

Dr. Kawana didn’t just want to plant some cherry blossoms and call it a day. He was obsessed with the idea of meigakure, or "hide and reveal." You walk five steps, the view changes. You turn a corner, a stone lantern appears. It’s tactical. He designed the garden in the 1980s (it officially opened in 1984) to prove that reclaimed water could sustain something delicate and culturally significant.

✨ Don't miss: How Long Ago Did the Titanic Sink? The Real Timeline of History's Most Famous Shipwreck

Breaking Down the Three Gardens in One

Most people think it’s just one big park. It’s not. It’s actually three distinct styles of Japanese gardening stitched together.

First, you hit the Zen meditation garden. It’s dry. It’s minimalist. Think raked gravel and large, intentional stones. It’s meant to represent the ocean and mountains without using a single drop of actual water. It’s a mental palate cleanser.

Then, you transition into the wet strolling garden. This is where the reclaimed water from the Tillman plant really shows off. There’s a massive lake, waterfalls, and streams. The water is filtered to a "tertiary" level, meaning it’s incredibly clean—clean enough that the koi fish living in the ponds are some of the healthiest you’ll see in the city. The sheer volume of water moving through the site is staggering. It doesn't smell like a treatment plant. It smells like wet stone and pine.

Finally, there’s the Tea Garden. This area is more intimate. It houses the Shoin building and a traditional tea house. Everything here is about scale. The paths are narrower, the plants are manicured with surgical precision, and the atmosphere shifts from "grand park" to "private sanctuary."

The "Star Trek" Connection and Valley Weirdness

If the garden looks familiar and you’ve never been there, you’re probably a nerd.

🔗 Read more: Why the Newport Back Bay Science Center is the Best Kept Secret in Orange County

The Tillman Water Reclamation Plant's administration building—which sits right on the edge of the garden—was used as the filming location for Starfleet Academy in Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Voyager. Its futuristic, brutalist-meets-modernist architecture creates this bizarre backdrop for the traditional Japanese flora. It’s peak Los Angeles. Where else can you meditate in a 17th-century style garden while staring at a building that represents the 24th century?

It’s a strange juxtaposition. On one side, you have the hyper-efficient, industrial reality of processing 40 million gallons of sewage a day. On the other, you have the silent, slow-growth world of bonsai and stone bridges.

Why the Design Actually Matters for Modern L.A.

We need to talk about the stones. Most visitors ignore them, but they are the literal bones of The Japanese Garden in Van Nuys. Dr. Kawana hand-picked over 600 tons of rock from the McCloud River in Northern California. He didn't just dump them there. Each stone has a "face" and a specific orientation.

In Japanese gardening, if the stones are wrong, the whole energy is off.

The garden serves a practical purpose beyond just being a film set or a place for a Sunday walk. It’s a massive cooling lung for the San Fernando Valley. In July, when Van Nuys is hitting 105 degrees, the garden is noticeably cooler. The evaporation from the lake and the shade from the black pines create a microclimate. It’s a living demonstration of how urban planning can integrate heavy utility with public beauty.

💡 You might also like: Flights from San Diego to New Jersey: What Most People Get Wrong

Practical Realities: Visiting SuihoEn

Let’s be real—you can’t just roll up here whenever you want. Because it’s located on the grounds of a high-security municipal facility (the water plant), access is more restricted than your average city park.

- Reservations are non-negotiable. You can’t just walk in. You have to book a time slot online through their official portal.

- Hours are weird. They are typically closed on Fridays and Saturdays. It’s a weekday and Sunday spot.

- The "No Food" Rule. This isn't a picnic park. They are very strict about this. Don't bring a cooler. Don't bring your dog. It’s a place for quiet reflection, not a frisbee session.

- Photography. If you’re a professional with a tripod, you’re going to need a permit. If you’re just snapping shots on your iPhone, you’re fine.

The Wildlife Factor

Despite being in the middle of an industrial zone, the garden is a massive bird sanctuary. Because of the constant flow of clean, reclaimed water, you’ll see Great Blue Herons, Snowy Egrets, and various species of ducks that have no business being in the middle of the Valley. The koi are the main event, though. Some of them are massive. They are fed a specific diet by the staff, and watching them swarm near the bridges is a highlight for anyone with kids.

Misconceptions About the Water

I hear people say, "Oh, I'm not touching that water, it's recycled."

Look. The water in this garden is likely cleaner than the water in the Los Angeles River or even some of the local reservoirs. The Tillman plant uses a multi-stage cleaning process: primary settling, secondary biological treatment, and tertiary filtration with chlorine disinfection. By the time it hits the garden’s waterfalls, it’s remarkably clear. It then flows back out to the Sepulveda Basin and eventually into the L.A. River, helping to maintain the local ecosystem. It’s a closed-loop success story that more cities should be copying.

Actionable Steps for Your Visit

To get the most out of The Japanese Garden in Van Nuys, you need a plan.

- Check the Bloom Calendar. If you want the "classic" experience, go in early spring (typically March) for the cherry blossoms. However, the garden is designed to have "four seasons of beauty." The wisteria in late spring is underrated, and the lotus flowers in the summer are massive.

- Book the Earliest Slot. The light is better for photos, and it’s significantly quieter. By noon, even with the reservation system, the main paths can feel a bit crowded.

- Visit the Shoin Building. Don't just walk the perimeter. Go into the administrative areas where the architectural details—like the joinery and the tatami mats—are on full display.

- Look for the Lanterns. There are several stone lanterns gifted by Los Angeles’ sister city, Nagoya. Each one has a different history and design.

- Pair it with the Sepulveda Basin Wildlife Reserve. If you still have energy after your stroll, the wildlife reserve is just a five-minute drive away. It’s a rougher, more "wild" version of the Valley’s water management system and offers a great contrast to the manicured perfection of the Japanese Garden.

This place isn't just a park; it's a statement about what Los Angeles can be when it tries to balance its thirst for water with its need for soul-soothing spaces. It’s proof that you can build a sanctuary out of the things we usually try to hide underground.