Money stopped moving. That’s the simplest way to describe what happened starting in 1929. When people talk about the inflation rate Great Depression era, they usually get the direction of the price movement wrong. Prices didn't skyrocket. They fell off a cliff.

Honestly, we’re so used to seeing the price of eggs or gas go up every year that the concept of a "negative" inflation rate feels like a weird fantasy. But between 1929 and 1933, the U.S. didn't have inflation; it had a brutal, soul-crushing period of deflation. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) dropped by about 27%. Imagine waking up and finding out your house is worth 30% less, but your mortgage payment stayed exactly the same. That was the trap.

It was a disaster.

The Tricky Math of the Inflation Rate Great Depression Era

Economists like Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz later pointed out that the Federal Reserve basically fell asleep at the wheel. Or worse, they intentionally tightened the belt when the economy needed a loose pair of sweatpants. Because the money supply shrank by a third, the value of a single dollar technically went up. If you had cash under your mattress, you were getting "richer" by doing nothing.

But nobody had cash.

Most people were watching their wages disappear or their jobs vanish entirely. This is why looking for a high inflation rate Great Depression figure is a wild goose chase. You have to look at the "Real Interest Rate." If the nominal interest rate is 5% but prices are falling by 10%, your "real" cost of borrowing is actually 15%. That is a debt trap. It’s why farmers in Iowa were losing land they’d owned for generations—they couldn't sell enough corn to pay back loans that were now effectively three times more expensive than when they signed the paperwork.

The numbers are staggering when you look at the specifics. In 1930, the inflation rate was -6.4%. In 1931, it hit -9.3%. By 1932, it peaked (or bottomed out) at -10.3%.

Think about that.

If you bought a car for $600, a year later a brand-new version of that same car might be $540. You’d think, "Hey, cheap cars!" But if your boss just cut your pay by 20% or fired you, that $540 car is more out of reach than the $600 one was. This is the "deflationary spiral." It’s a psychological monster. If you know a TV will be cheaper next month, you don't buy it today. If everyone does that, the factory closes. Then you lose your job. Then you really can't buy the TV.

Why the Gold Standard Made Everything Worse

We can't talk about prices without talking about gold. Back then, the U.S. was tied to the Gold Standard. This meant the government couldn't just print money to stimulate the economy like they did during the 2020 pandemic. They were handcuffed.

To keep gold from flowing out of the country, the Fed actually raised interest rates in 1931. Yes, you read that right. While the world was collapsing, they made it harder to get money. It’s like trying to put out a fire with a canister of gasoline. It accelerated the drop in the inflation rate Great Depression statistics, pushing the country deeper into the hole.

Irving Fisher, a famous economist of the time, developed the "Debt-Deflation Theory." He argued that trying to pay off debt when prices are falling actually makes you more broke. You’re liquidating assets to pay down a debt that is growing in "real" value faster than you can pay it. It’s a treadmill set to 10.0 speed while you’re wearing lead boots.

💡 You might also like: The UAE and Saudi Arabia Rivalry: What Most People Get Wrong

What about the 1930s "Reflation"?

By 1933, things started to pivot. Franklin D. Roosevelt took office and immediately devalued the dollar against gold. This was a massive shock to the system. Suddenly, the inflation rate Great Depression narrative shifted from "falling prices" to "trying to make prices go up again."

He wanted "reflation."

Roosevelt basically told the public that the government wanted prices to go back to 1929 levels. He knew that for the economy to breathe, people needed to stop hoarding cash. Between 1934 and 1937, the U.S. actually saw some inflation—about 2% to 3% annually. It felt like a recovery. But the ghost of the depression wasn't gone. In 1937, the government got scared of inflation (ironically) and cut spending while the Fed tightened the money supply again.

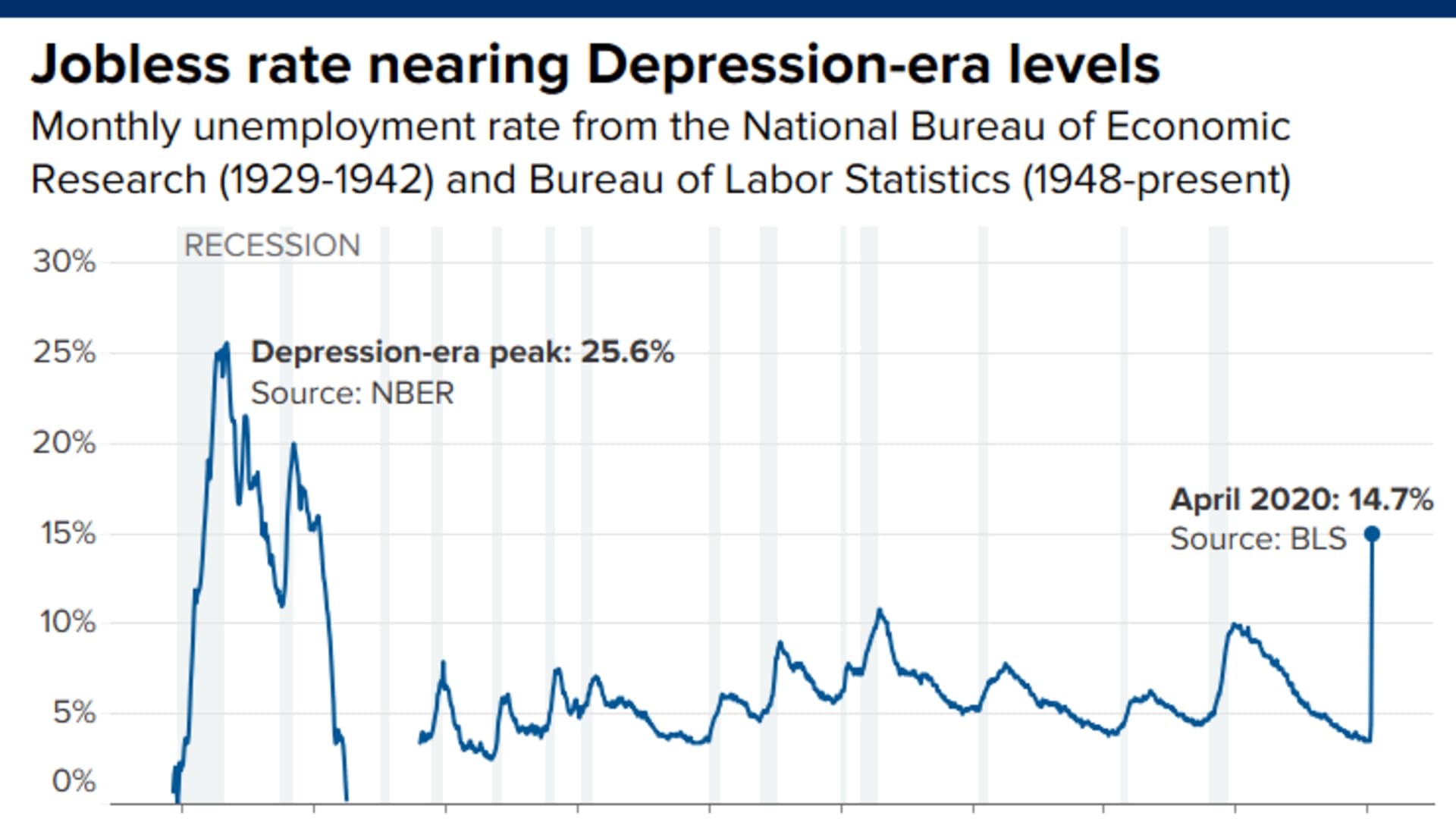

The result? The "Recession within the Depression." Prices flattened out again, and unemployment, which had been dropping, spiked back up to 19%.

Real World Parallels: Why This Matters Now

You might wonder why we obsess over these old numbers. It’s because the inflation rate Great Depression data serves as a warning for modern central banks. It’s why, in 2008 and 2020, the government flooded the gates with liquidity. They are terrified of deflation.

Inflation is annoying. It makes your groceries expensive. But deflation is a killer. It destroys the incentive to invest.

✨ Don't miss: How to Use a New York City Tax Calculator Without Getting Burned

Lessons for the Modern Investor

If you’re looking at these historical cycles to protect your own money, there are a few blunt truths to swallow.

First, cash is king during deflation, but it's a trap during the recovery phase. Those who held onto cash in 1932 did great until the dollar was devalued in 1933. Then, their purchasing power took a hit relative to gold and stocks.

Second, debt is your worst enemy when the inflation rate goes negative. In a normal world, inflation eats your debt—you pay back "cheaper" dollars. In a Great Depression scenario, your debt eats you.

Third, diversification isn't just a buzzword; it's a survival strategy. During the 1930s, almost everything correlated to the downside except for high-quality bonds and, eventually, gold-related assets after the 1933 transition.

How to Monitor Economic Health Today

Forget the headlines for a second. If you want to see if we’re heading toward a 1930s-style event, watch the "Velocity of M2 Money Stock." This is a fancy way of saying "how fast is a dollar moving through the economy?" During the Great Depression, velocity plummeted. People stopped spending, and the money just sat there.

Also, keep an eye on the "Inverted Yield Curve." While it's often cited as a recession predictor, it’s really a sign of what the market thinks about future interest rates and inflation. If the market expects the inflation rate Great Depression style—meaning a total collapse in pricing power—you’ll see long-term rates drop significantly below short-term rates.

Actionable Steps for Financial Resilience

You can't control the Federal Reserve, but you can control your own balance sheet. History shows that those who survived the 1930s weren't necessarily the ones with the most money—they were the ones with the least "inelastic" debt.

- Kill High-Interest Debt Now. If we ever hit a period of stagnant or negative inflation, that 20% credit card interest will feel like 40%. Get rid of it while the dollar is still losing value (which makes it easier to pay off).

- Maintain a Liquid Emergency Fund. Not in "investments," but in actual cash or equivalent. When the inflation rate Great Depression era hit, the biggest problem wasn't a lack of wealth; it was a lack of liquidity. People had land but no cash to pay taxes.

- Watch the Real Interest Rate. Don't just look at the number the bank gives you. Subtract the current inflation rate from it. If the result is rising, the "cost" of your money is going up, regardless of what the news says.

- Tangible Assets vs. Paper. In the depths of the 1930s, "stuff" had a floor value while "paper" (stocks in bankrupt companies) went to zero. Owning things with utility—tools, land, skills—provides a hedge that a brokerage account cannot.

Understanding the inflation rate Great Depression isn't just a history lesson. It's a lens for viewing risk. We live in a world designed for 2% inflation. If that ever flips, the rules of the game don't just change—they invert. Stay liquid, stay skeptical of massive debt, and always watch the velocity of the money in your own local economy.