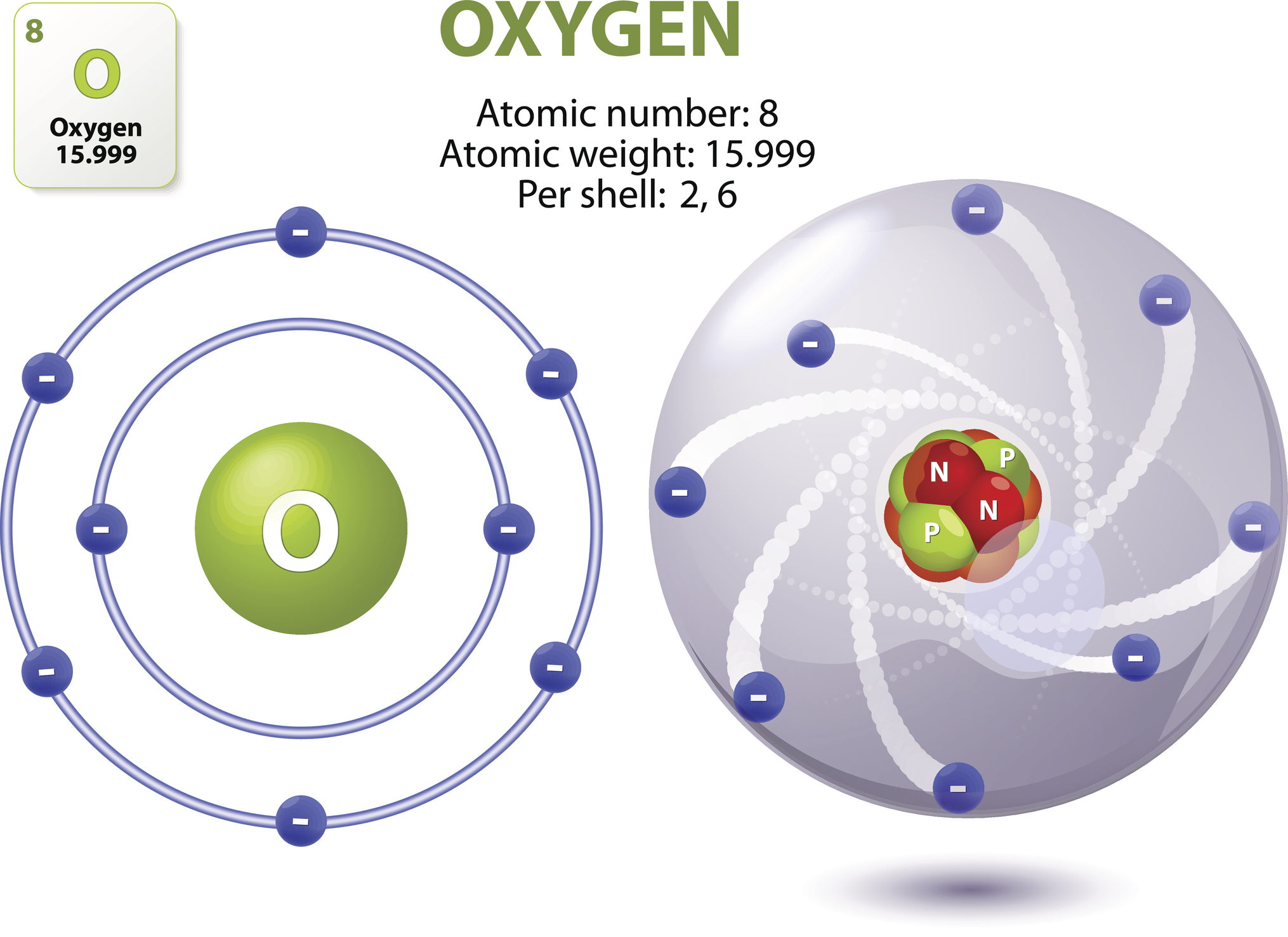

You’ve seen it a thousand times. A central clump of red and blue balls—protons and neutrons—circled by little planet-like electrons zipping around on neat, elliptical tracks. It’s the classic image of oxygen atom structures found in every middle school textbook from here to Tokyo. It looks organized. It looks like a tiny solar system.

It's also mostly a lie.

Well, "lie" is a bit harsh. It’s a map. But just like a subway map doesn't show you the actual grit on the tracks or the smell of the station, the Bohr model doesn't show you what oxygen actually looks like. If you could actually "see" an oxygen atom—which is a massive "if" given the laws of physics—it wouldn't look like a graphic design project. It would be a fuzzy, vibrating ghost.

The Problem With "Seeing" Oxygen

When we talk about an image of oxygen atom components, we run into a wall called the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle. Basically, you can't know exactly where an electron is and how fast it’s going at the same time. In the world of the very small, things don't sit still for photos.

Most people think oxygen looks like a ball. It’s actually more like a cloud.

Think about a fan. When it’s off, you see three distinct blades. When you flip the switch to high, the blades disappear into a translucent blur. Electrons are like that, but infinitely faster and weirder. They exist in "orbitals," which are basically just mathematical "maybe" zones. For oxygen, which has eight electrons, these zones look like dumbbells and spheres stacked on top of each other.

What Modern Microscopy Actually Shows Us

We’ve actually gotten closer than you might think to a real image of oxygen atom clusters. We use things like Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) and Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM). These aren't cameras. They don't use light. They use a tiny, needle-sharp tip to "feel" the electron clouds of atoms.

Back in 2009, researchers at IBM Research – Zurich managed to capture an image of a pentacene molecule. You could see the carbon and hydrogen atoms. More recently, scientists have used photoemission electron microscopy to map the wave functions of electrons.

When you look at these high-tech images, oxygen doesn't look like a solar system. It looks like a bright, grainy blob. The "image" is actually a heat map of where the electrons are most likely to be. The center—the nucleus—is so unimaginably small compared to the electron cloud that if the atom were the size of a football stadium, the nucleus would be a marble in the center, and the electrons would be like gnats buzzing around the very top seats of the stands. Everything else is just empty space.

Why Oxygen is Shifting Under Your Feet

Oxygen is an aggressive atom. It’s the "bad neighbor" of the periodic table. Because it has six electrons in its outer shell, it’s constantly trying to steal two more to reach a stable "octet" of eight. This is why oxygen is so reactive.

When you see a digital image of oxygen atom bonding, like in a water molecule ($H_2O$), the oxygen atom looks like it's holding hands with two hydrogen atoms. In reality, it has warped their electron clouds. It’s pulling the "blanket" of electrons toward itself. This creates a polar charge. This simple tug-of-war is the reason water has surface tension and the reason you are alive right now.

If oxygen weren't so "greedy" for electrons, the chemical bonds that build proteins and DNA wouldn't happen the same way.

📖 Related: Small Engine Repair Cast: Why Your Equipment Is Failing and How to Fix It

The Misleading Colors of Science

If you Google an image of oxygen atom right now, it’s probably red.

Why red? There’s no real reason. Atoms don't have color in the way we think. Color is a property of how light reflects off large groups of atoms. A single oxygen atom is smaller than the wavelength of visible light. It’s literally "colorless" because light just flows around it like water around a single pebble in a river.

The CPK coloring system (named after Corey, Pauling, and Kultun) assigned red to oxygen decades ago. It’s just a convention to help chemists keep track of things in a model. Hydrogen is white, carbon is black, and nitrogen is blue. If you saw a "real" oxygen atom, it wouldn't be red. It would be invisible.

The Quantum Reality vs. The Graphic

Quantum mechanics tells us that the electrons in an oxygen atom are in a state of constant, frantic probability. There are two electrons in the inner 1s orbital (a sphere). Then there are two in the 2s orbital (a larger sphere). Finally, there are four in the 2p orbitals (which look like three crossed dumbbells).

When you stack all that together, the image of oxygen atom structures becomes a messy, overlapping sphere of energy.

It’s not neat.

It’s not pretty.

It’s chaotic.

But that chaos is what allows oxygen to bind with iron in your blood to carry energy to your brain. It’s what allows it to spark fire. It’s what allows it to form the ozone layer that protects us from getting fried by the sun.

How to Visualize it Better

If you want to have a more accurate mental image of oxygen atom behavior, stop thinking about objects. Start thinking about vibrations.

Imagine a bell ringing. You can't see the sound, but you can feel the vibration in the air. An atom is more like a standing wave of energy than a solid piece of matter. The "solid" feeling of a table or a breath of air is just the electromagnetic repulsion of these vibrating clouds pushing against each other.

Real-World Applications of Atomic Imaging

We aren't just taking these "pictures" for fun. Mapping the electron density of oxygen is vital for:

- Drug Discovery: If we know exactly how the electron cloud of an oxygen atom in a virus protein looks, we can design a drug molecule that fits into it like a key.

- Battery Tech: Lithium-oxygen batteries are a huge area of research. Understanding the oxygen interface at the atomic level could lead to phones that last a week.

- Materials Science: Creating rust-resistant metals requires knowing exactly how oxygen atoms "attack" the surface of iron.

Moving Beyond the Textbook

The next time you see a simplified image of oxygen atom models, remember that you’re looking at a caricature. It’s a stick-figure drawing of a complex, quantum-mechanical masterpiece.

Science is moving away from the "ball and stick" era. We are entering the era of probability mapping and wave-function imaging. It’s weirder, harder to draw, and significantly more fascinating than anything in a 1990s textbook.

✨ Don't miss: Red Stars: What Most People Get Wrong About the Coolest Color in Space

To get a better grasp on this, look into "Electron Probability Density" maps rather than "atomic models." These visualizations use dots to show where an electron is likely to be at any given nanosecond. The denser the dots, the "sturdier" the atom. It’s the closest we can get to the truth without breaking the laws of physics.

Focus on the following steps to refine your understanding of atomic structures:

Study the "Schrödinger's Equation" visualizations for the second-row elements to see how p-orbitals actually overlap. Compare the "Bohr Model" with the "Quantum Mechanical Model" side-by-side to identify where the solar system analogy fails. Finally, look at real AFM (Atomic Force Microscopy) data from university labs like UC Berkeley or the Max Planck Institute to see how scientists interact with single atoms today.