August 28, 1963. It was hot. Humidity in D.C. usually feels like a wet blanket, and that Wednesday was no different. Over 250,000 people stood around the Reflecting Pool, their feet aching, waiting for something to shift. When Martin Luther King Jr. stepped up to the podium, he wasn't just another speaker in a long lineup. He was the climax. But here’s the thing most people forget: the most famous part of the I Have a Dream speech wasn't even in the script.

He had a prepared text. It was good. It was professional. But it wasn't the speech. About halfway through, Mahalia Jackson—the legendary gospel singer who had just performed—shouted from behind him, "Tell 'em about the dream, Martin!"

He stopped reading.

He clutched the lectern.

And then he went off-script. That pivot changed everything.

The Raw Reality Behind the March on Washington

We often see the grainy, black-and-white footage and think it was this neat, organized moment of national unity. It really wasn't. The Kennedy administration was terrified. They had thousands of troops on standby because they expected a riot. They even had an "emergency" switch to cut the power to the sound system if things got "incendiary."

The I Have a Dream speech happened in a pressure cooker. This wasn't just a "feel good" moment for the history books; it was a desperate plea for basic human dignity in a country that was actively firehosing children in places like Birmingham.

People think the "Dream" was a Hallmark card. Honestly, it was a radical demand. King wasn't just talking about kids holding hands. He was talking about a "promissory note" that had bounced. He was calling out the "tranquilizing drug of gradualism." He wanted change right then.

That "Promissory Note" Metaphor Everyone Skips

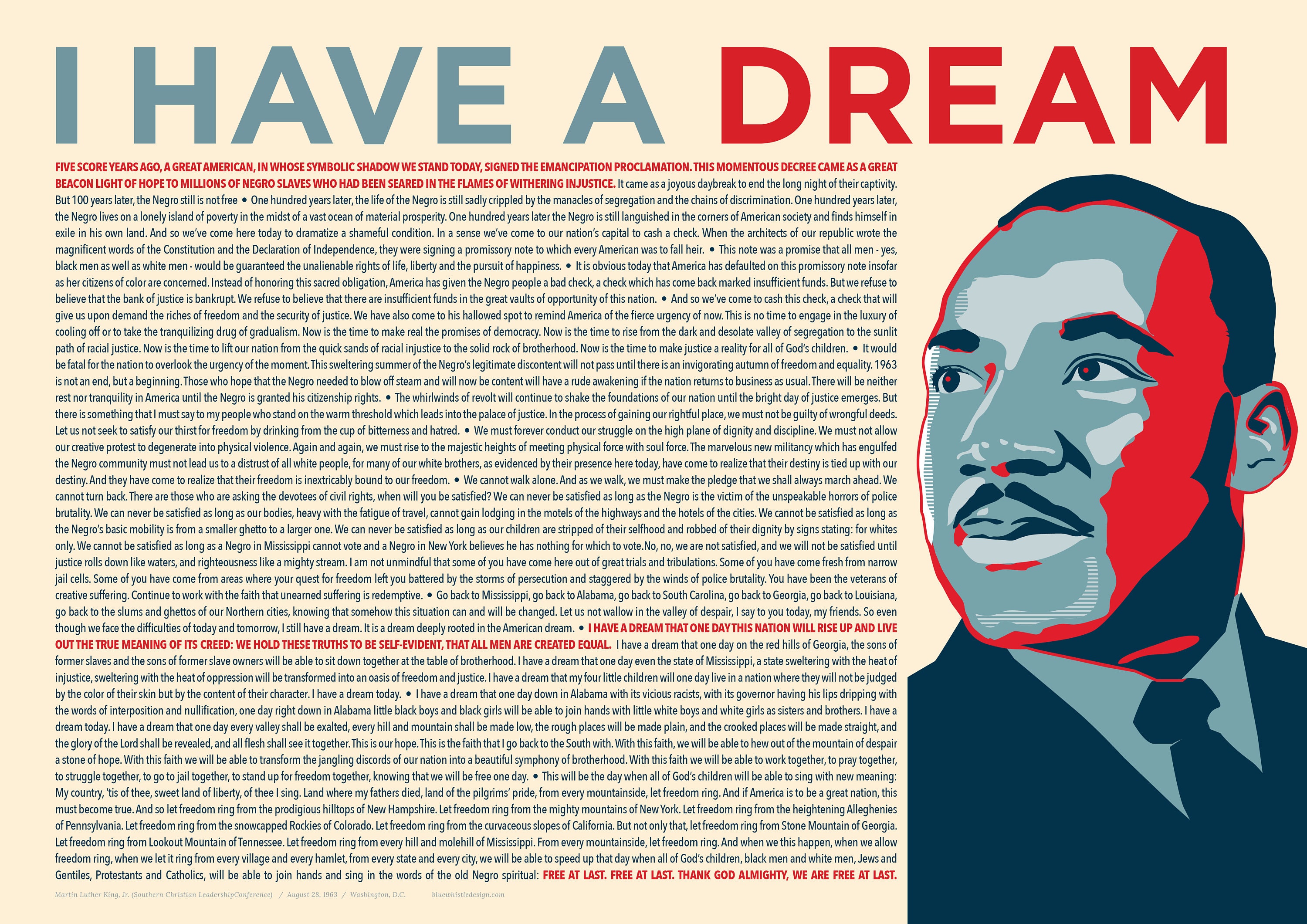

If you look at the actual text of the I Have a Dream speech, King spends a huge chunk of time on banking metaphors. It sounds weird, right? But it was brilliant. He talked about the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence as a check. He said America had defaulted on this check for Black citizens, giving them a "bad check" marked "insufficient funds."

- He didn't start with the dream.

- He started with the debt.

- He demanded payment.

This wasn't just poetry; it was a legal argument wrapped in the cadence of a Sunday morning sermon. He was speaking to the white moderates who were always telling him to "wait for a better time." King’s point was that the time for waiting had passed decades ago.

The Mahalia Jackson Influence

You've gotta understand the relationship between King and Mahalia Jackson. She was his secret weapon. Whenever he felt stuck or discouraged, he’d call her up and ask her to sing to him over the phone. On that day in August, she knew he was playing it too safe with his written notes.

When she yelled at him to talk about the dream, she was referencing a theme he’d experimented with before. He had given similar versions of that "dream" sequence in Detroit and Rocky Mount, North Carolina, earlier that year. But on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, with the weight of the entire world watching, it hit differently.

The rhythm changed. His voice went from "lecturer" to "prophet." The "I have a dream" refrain acts like a chorus in a song. It’s repetitive because it has to be. It builds tension until it breaks into that final, soaring hope.

🔗 Read more: The Most Accurate Polls 2020: What Really Happened Behind the Headlines

Why the Ending Still Gives Us Chills

"Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!"

Those words weren't his. He was quoting an old spiritual. That’s the genius of the I Have a Dream speech—it’s a mashup. He’s pulling from the Bible (Amos and Isaiah), from "My Country, 'Tis of Thee," and from the deep, painful history of enslaved people's music.

It worked because it forced the audience to look at the gap between what America said it was and what it actually was. He used the scenery. Standing in the shadow of Abraham Lincoln while calling out the fact that 100 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, Black people still weren't free? That’s top-tier rhetorical staging.

Common Misconceptions About the Day

A lot of folks think the I Have a Dream speech ended racism overnight. Or that everyone loved it. They didn't. The FBI’s William Sullivan wrote a memo afterward calling King the "most dangerous Negro of the future in this Nation." They didn't see a dreamer; they saw a threat to the status quo.

Also, the march wasn't just about "Civil Rights." The official title was the "March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom." Economics were at the heart of it. King knew that you couldn't truly be free if you didn't have a living wage or a decent place to live. He was pushing for a $2.00 minimum wage—which, adjusted for inflation today, would be quite a bit.

How to Actually Apply King’s Rhetoric Today

If you’re a writer, a leader, or just someone who wants to understand why some words stick while others fade, look at King’s use of "The Contrast."

💡 You might also like: ICE Raids Explained: What Actually Happens During Enforcement Actions

He doesn't just stay in the clouds with the dream. He constantly dips back down into the "dark and desolate valley of segregation." You can't have the light of the dream without acknowledging the darkness of the reality.

- Be Specific: He didn't just say "the South." He named Mississippi, Alabama, South Carolina, Georgia, and Louisiana. He made it personal.

- Use Allusions: He leaned on documents his audience already respected (The Bible and the Constitution) to make his radical ideas feel familiar and "American."

- The Power of the Pause: If you listen to the recording, the silences are just as heavy as the words.

The Legacy of the 1,667 Words

The I Have a Dream speech is only about 17 minutes long. In the grand scheme of history, that’s a blink. Yet, we’re still dissecting it over 60 years later. It’s taught in almost every public school in the U.S., but often, we teach the "sanitized" version.

We forget the parts where he warned about the "whirlwinds of revolt." We forget that he called out police brutality. To truly honor the speech, you have to read the uncomfortable parts, not just the quotes that look good on Instagram.

It remains a masterclass in hope as a political tool. King wasn't being naive. He knew exactly how much hate was out there. He just chose to believe that the "arc of the moral universe" could be bent toward justice if enough people pulled on it at the same time.

Take Action: How to Engage with the Speech Today

To move beyond the surface-level understanding of this moment, start with these specific steps:

- Read the Unedited Transcript: Don't just watch the 3-minute clips on YouTube. Read the full text from the King Center or the Stanford University archives. Pay attention to the "Bad Check" section in the first third of the speech.

- Listen to the Audio: There is a cadence in King’s voice that print cannot capture. Listen for where he breathes and where he slows down. Notice how the crowd’s energy changes when he moves into the "Dream" sequence.

- Research the Context: Read about the other speakers that day, like John Lewis. Lewis’s original speech was actually censored by other leaders for being too radical. Understanding the tension between the speakers gives the I Have a Dream speech a whole new layer of meaning.

- Connect it to the Present: Look at current economic and social data regarding the "promissory note" King mentioned. Evaluate for yourself where the "funds" are still insufficient in modern society.

The power of the speech isn't that it's a finished historical artifact. It's that the "check" is still out there, waiting to be cashed.