Hollywood loves a good prison break. You've got The Shawshank Redemption, Escape from Alcatraz, and about a dozen others that everyone knows by heart. But honestly, most people have completely overlooked the House of Numbers 1957 film. It's weird. It stars Jack Palance playing two different people—identical twins—and it was actually filmed inside San Quentin. Not a set. Not a soundstage. The real, gritty, 1950s San Quentin State Prison.

Most movies from that era feel a bit stagey, right? Not this one. Director Russell Rouse took a gamble on realism that still feels surprisingly modern. If you're a fan of noir or just like a heist movie where things actually feel like they're at stake, this is one you need to track down.

The Dual Performance of Jack Palance

Jack Palance is usually the guy you remember as the terrifying villain with the sharp cheekbones. In the House of Numbers 1957 film, he pulls double duty. He plays Bill Judlow, a guy stuck in San Quentin for life, and his brother Arnie, who is on the outside trying to get him out.

It’s a gimmick, sure. But it works because Palance plays them so differently.

Bill is the hardened one. He’s been behind bars long enough to know the rhythm of the place. Arnie is the nervous one, the guy who has to learn how to move like a convict to pull off the switch. Watching one man play both roles in the same frame—back when they had to do this with split-screens and careful blocking—is a masterclass in old-school technical filmmaking.

Why the Twin Angle Matters

The whole plot hinges on the fact that these two look exactly alike. It’s not just a "Prince and the Pauper" story; it’s a high-stakes shell game. Arnie sneaks into the prison to take Bill's place temporarily, allowing Bill to sneak out, handle some business, and then sneak back in.

Wait. Sneak back in?

Yeah. That’s the twist. Most prison movies are about leaving and never looking back. In the House of Numbers 1957 film, the challenge is the round trip. It’s about the logistics of the "in-and-out" that makes your head spin if you think about it too hard, but Rouse keeps the pace so tight you just go with it.

San Quentin: The Uncredited Star

You can’t talk about this movie without talking about the location. Most 1950s films were shot on the backlots of MGM or Warner Bros. Everything looked a little too clean. The House of Numbers 1957 film is different.

The production actually got permission to film inside San Quentin.

When you see the long corridors, the cramped cells, and the massive dining hall, those are the real deal. You can almost smell the stale coffee and floor wax. It adds a layer of claustrophobia that you just can't manufacture on a set.

The extras? Many of them were actual inmates and guards.

👉 See also: Nothing to Lose: Why the Martin Lawrence and Tim Robbins Movie is Still a 90s Classic

Imagine being an actor and standing in a line of real convicts. That’s going to change your performance. Palance looks genuinely stressed in some of those scenes, and it’s probably because he was surrounded by guys who weren't there for the craft of acting. It gives the film a documentary-like quality that was years ahead of its time.

The Logistics of the Escape

The escape plan in the House of Numbers 1957 film isn't about digging a tunnel with a rock hammer. It’s about timing. It’s about knowing exactly when the guards shift, how the laundry is moved, and where the blind spots are in the yard.

It's methodical.

Arnie spends a significant portion of the film basically "training" to be a prisoner. He has to learn the walk. The talk. The way a man carries himself when he has nothing but time. This part of the movie is honestly the most fascinating because it deconstructs the "convict" persona. It suggests that being a prisoner is a performance in itself.

Jack Palance: More Than Just a Villain

We often pigeonhole Palance as the heavy. Think Shane or City Slickers. But here, he gets to show range. As Arnie, he’s vulnerable. He’s a guy way out of his depth, driven by a misguided sense of loyalty to a brother who might not even deserve it.

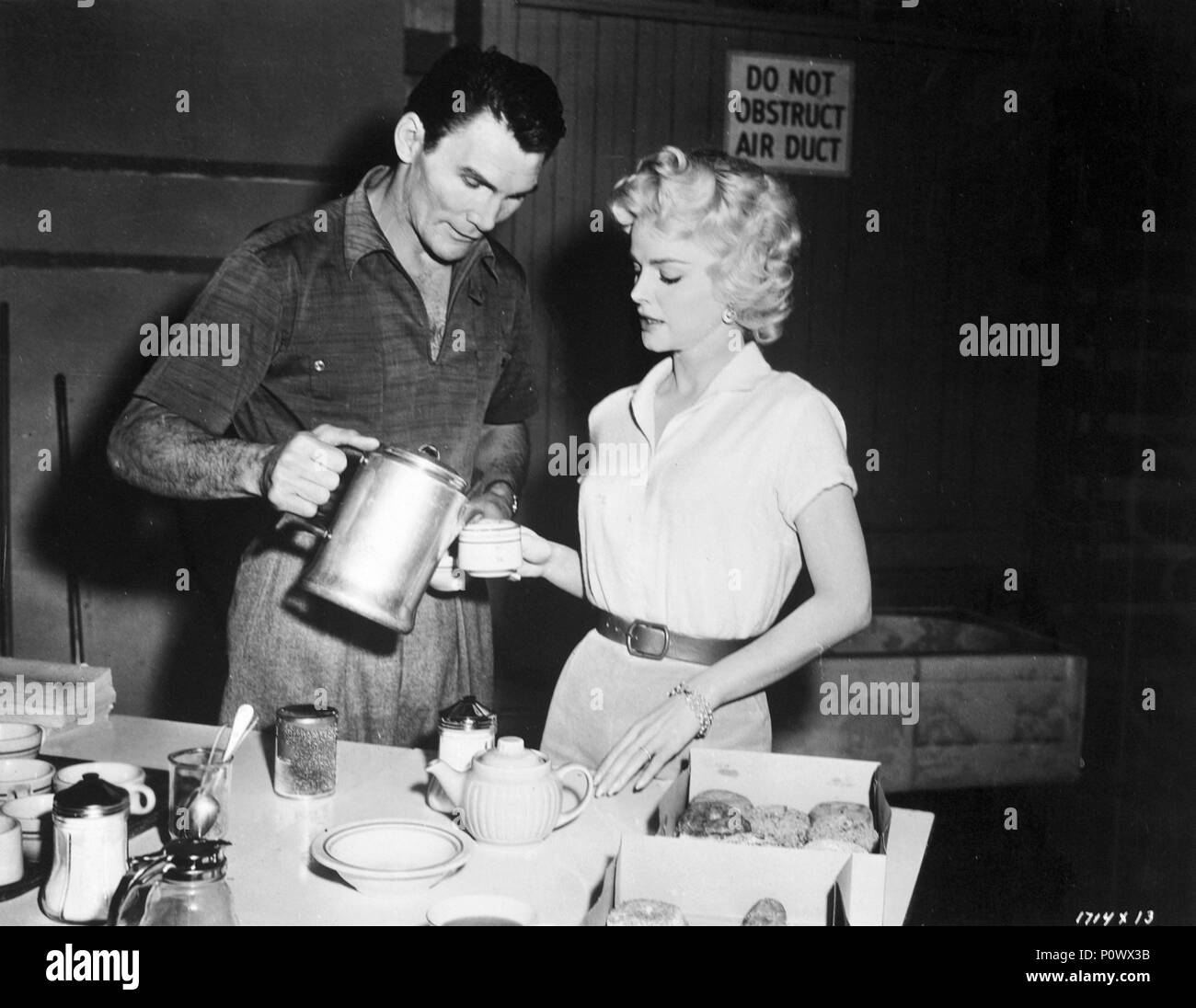

Then there's Barbara Lang. She plays Ruth, Bill's wife, who is caught in the middle of this insane scheme.

Her chemistry with both "versions" of Palance is what grounds the movie. Without that emotional core, it would just be a technical exercise in split-screen photography. She brings the stakes. If the plan fails, she doesn't just lose one man; she potentially loses both.

A Noir Aesthetic in Broad Daylight

Film noir usually implies dark alleys and rainy streets. The House of Numbers 1957 film brings that sensibility into the harsh, fluorescent-lit world of a penitentiary. Cinematographer George J. Folsey does incredible work here.

He uses the bars of the cells to create shadows that literally trap the characters in the frame.

Even when they are in the "yard" under the California sun, there’s a sense of being watched. The camera work is restless. It mimics the anxiety of the characters. You’re always waiting for that one guard to look a little too closely at Arnie’s face or for a cellmate to notice that Bill’s "brother" doesn't know the secret handshake.

What Most People Get Wrong About 50s Thrillers

There's this idea that movies from 1957 are "tame."

✨ Don't miss: How Old Is Paul Heyman? The Real Story of Wrestling’s Greatest Mind

People think they lack the grit of modern cinema. But the House of Numbers 1957 film proves that wrong. It deals with identity, the moral rot of the prison system, and the desperation of the working class in a way that feels incredibly cynical.

It doesn't have a "happy" ending in the traditional Hollywood sense. It’s messy.

The film also avoids the trap of making the prisoners out to be misunderstood heroes. Bill is a criminal. He’s in there for a reason. The movie doesn't ask you to forgive him; it just asks you to watch him try to beat the system. That moral ambiguity is what makes it a true noir.

The Screenplay and the Source Material

The movie was based on a story by Jack Finney. If that name sounds familiar, it's because he wrote The Body Snatchers.

Finney was a master of the "what if" scenario. His stories always take one impossible premise and then treat it with absolute, logical realism. In Invasion of the Body Snatchers, it’s alien pods. In the House of Numbers 1957 film, it’s the idea that a man can be in two places at once if he has a twin and a death wish.

The screenplay, co-written by Rouse and Don Mankiewicz, keeps that logic tight. They don't take shortcuts. Every time you think, "Wait, why don't the guards just check his ID?" the movie has an answer. It respects the audience's intelligence.

Technical Feats of 1957

Back then, you couldn't just use CGI to put two Jack Palances in the same room.

They used a technique called "optical masking." Essentially, they would film one half of the scene with Palance on the left, then rewind the film and shoot the other half with him on the right.

It required pinpoint precision.

If Palance moved an inch too far to the center, he’d disappear or overlap with himself. The fact that there are scenes in the House of Numbers 1957 film where the two brothers interact—passing items or talking over each other—is a testament to how much effort went into the production. It’s seamless. You forget you’re watching a trick.

The Sound of Silence

Another thing you'll notice is the sound design. Or rather, the lack of it.

🔗 Read more: Howie Mandel Cupcake Picture: What Really Happened With That Viral Post

Modern movies use bombastic scores to tell you how to feel. Rouse uses the natural sounds of the prison. The clanging of metal doors. The shuffling of feet. The distant shout of a guard. It builds a tension that a symphony orchestra never could.

When the escape finally happens, the silence is deafening. Every accidental scrape of a shoe feels like a gunshot. It’s incredibly effective filmmaking that relies on the viewer’s nerves rather than their ears.

Why It Still Matters Today

The House of Numbers 1957 film isn't just a museum piece.

It’s a blueprint for the "impossible" heist. You can see its DNA in movies like Ocean's Eleven or even The Prestige. It’s about the art of the con. It’s about using people's perceptions against them.

In an era where we are constantly worried about identity theft and deepfakes, a movie about a man literally "hacking" a physical location by using his own face is strangely relevant. It reminds us that the most effective security systems—whether they are stone walls or digital firewalls—all have a human element that can be exploited.

The Legacy of Russell Rouse

Russell Rouse is a name that doesn't get brought up enough in film school. He was a guy who loved puzzles. His films are often built around a singular, clever hook.

With the House of Numbers 1957 film, he proved that you could make a high-concept thriller without losing the human element. He didn't let the gimmick of the twins overshadow the drama of the characters. That’s a hard balance to strike.

If you look at his other work, like The Thief (1952), which has no dialogue at all, you see a director who was obsessed with pushing the boundaries of how stories are told. He was a tinkerer. A cinematic engineer.

Finding the Movie

Finding a clean copy of the House of Numbers 1957 film can be a bit of a hunt. It doesn't pop up on the major streaming services every day. You usually have to dig into the TCM (Turner Classic Movies) archives or find a specialty DVD release.

Is it worth the effort? Absolutely.

It’s one of those "secret" movies that makes you feel like an insider once you've seen it. When your friends are talking about the same five classic movies they've seen a dozen times, you can drop this one into the conversation. It’s the ultimate "hidden gem."

Actionable Steps for Film Buffs

If you're ready to dive into the world of 50s prison noir, here is how to get the most out of the experience:

- Watch for the Split-Screens: Pay close attention to the scenes where both brothers are on screen. Try to spot the "seam." It’s incredibly hard to find, which shows just how good the MGM lab technicians were in 1957.

- Research San Quentin History: The prison has changed immensely since the 50s. Looking at the film as a historical document of the California penal system adds a whole new layer of interest.

- Compare the Performances: Watch Palance’s eyes. He changes his gaze depending on which brother he is playing. Bill has a "thousand-yard stare," while Arnie’s eyes are constantly darting around. It’s subtle, but it’s there.

- Check out Jack Finney’s original story: If you can find the source material, it’s a great read. Seeing how the screenwriters adapted the internal logic of a book into visual beats is a lesson in storytelling.

- Double Feature it: Pair this with Escape from Alcatraz. Seeing the difference between 1957 and 1979 filmmaking—both using real prison locations—is a fascinating study in how the "gritty" aesthetic evolved in Hollywood.

The House of Numbers 1957 film remains a masterclass in tension, technical ingenuity, and noir storytelling. It’s a reminder that you don't need a hundred-million-dollar budget to create a heart-pounding thriller. You just need a solid hook, a couple of Jack Palances, and some very high stone walls.