If you only know Frank Underwood from the Netflix series, you're basically missing half the story. Honestly, the original House of Cards novel by Michael Dobbs is a different beast entirely. It’s meaner. It’s colder. It feels like it was written by someone who actually saw the blood on the floor of the House of Commons, which, to be fair, Dobbs did. He was a high-level Conservative Party operative who wrote the book after a massive fallout with Margaret Thatcher.

You can feel that bitterness on every page.

Most people think of Kevin Spacey’s Southern drawl or the slick, high-budget cinematography of the American remake. But the 1989 book? It’s set in the gray, rainy streets of London during the post-Thatcher power vacuum. It’s about Francis Urquhart—the "FU" that started it all.

The Brutality of Francis Urquhart

Francis Urquhart isn't just a politician. He’s a Chief Whip. In the British system, that means his literal job is to know every dirty secret, every gambling debt, and every illicit affair of his colleagues to keep them in line. He’s a "fixer."

The House of Cards novel presents a man who is arguably much more terrifying than his TV counterparts because his motives feel so petty and yet so grand. He doesn't want to change the world. He doesn't have a grand vision for America or the UK. He just wants the top job because he was passed over for a promotion.

That’s it.

The inciting incident isn't a world-ending crisis; it’s a bruised ego. After helping a new Prime Minister get elected, Urquhart expects a senior cabinet post. He’s told no. He’s told he’s too valuable where he is. So, he decides to burn the entire house down.

💡 You might also like: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

It’s chilling.

Why the Ending of the Book Still Scares People

We have to talk about Mattie Storin. In the Netflix version, Zoe Barnes gets pushed in front of a train. It’s shocking, sure. But in the original House of Cards novel, the dynamic between the journalist and the politician is even more twisted.

Mattie is younger, more vulnerable, and she starts calling Urquhart "Daddy." Yeah. It’s uncomfortable. It’s meant to be. It highlights the massive power imbalance that existed in the 1980s Westminster bubble.

When the end comes, it isn't a quick shove in a subway station. It’s a rooftop. And the way Dobbs writes the betrayal—the way Urquhart justifies it to himself—makes you want to take a shower. He’s a sociopath, but he’s a polite one. He uses the phrase "You might very well think that; I couldn't possibly comment" like a scalpel.

Interestingly, the BBC miniseries actually changed the ending of the book because it was too dark for the author’s liking at the time. In the first edition of the novel, Urquhart’s fate is very different. If you’re a fan of the show, you owe it to yourself to read the original text just to see how Dobbs originally intended for the "House of Cards" to collapse.

A Masterclass in Political Realism

Michael Dobbs didn't just guess how these people talk. He lived it. He was the "Baby-Faced Killer" of British politics. He served as an advisor to Thatcher and eventually became Lord Dobbs.

📖 Related: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

Because of this, the House of Cards novel is packed with tiny, realistic details about how power actually moves. It’s not about grand speeches. It’s about:

- Leaking a single document to a friendly journalist at 11 PM.

- Mentioning a "health problem" of a rival in a "casual" conversation.

- Knowing which MP is hiding a massive drinking problem.

The prose is sparse. It’s fast. You can finish it in a weekend, but the cynicism stays with you much longer. It captures a specific moment in British history where the old guard was dying out and a new, more ruthless type of politician was taking over.

The Difference Between the Novel and the Remakes

The US version expanded the story into a multi-season epic about the Presidency. The House of Cards novel is much tighter. It’s a tragedy in the classical sense. It’s about one man’s rapid ascent and the moral vacuum he leaves behind.

In the book, the political stakes feel smaller but the personal stakes feel much higher. There’s no Claire Underwood equivalent who acts as an equal partner. Urquhart is a lone wolf. His wife, Elizabeth, is supportive, but she isn't the co-conspirator that Robin Wright portrayed. This makes Urquhart feel more isolated and, frankly, more dangerous. He has no one to answer to.

It’s Not Just a Thriller

It’s a warning.

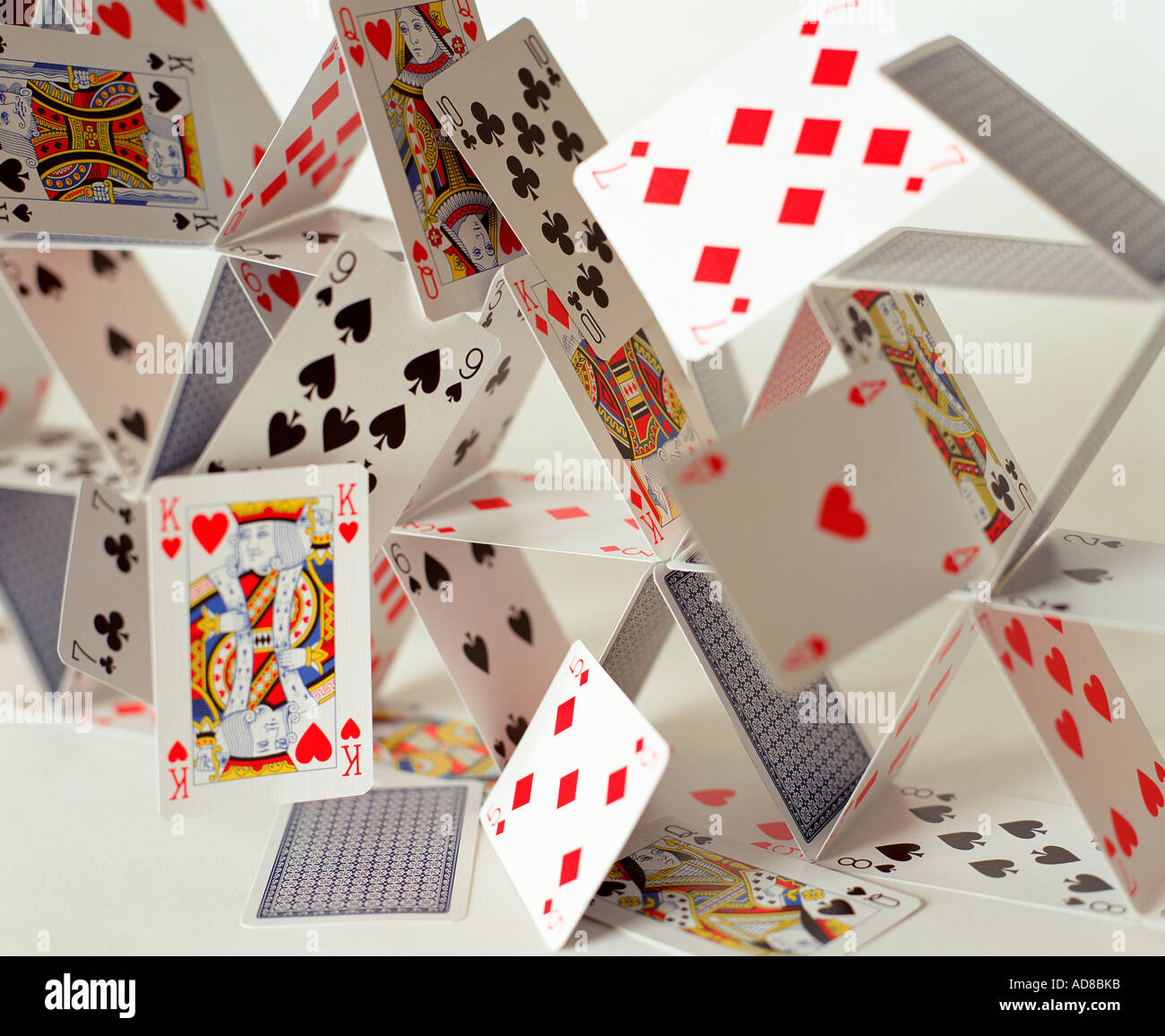

When Dobbs wrote this, he was disillusioned. You can see his fingerprints on every chapter. He wanted to show that the structures we think protect democracy are actually incredibly fragile. They are held together by "cards"—reputations and secrets that can be knocked over with a single breath.

👉 See also: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

If you’re looking for a deep dive into the psychology of power, skip the binge-watch for a second. Pick up the paperback. The way Urquhart manipulates the press in the House of Cards novel is especially relevant today. He doesn't just lie; he directs the truth toward his enemies.

How to Approach the Book Today

If you’re going to read it, don’t expect the high-octane drama of a modern thriller. Expect a slow-burn character study.

First, read it as a historical artifact. Look at how 1980s London is described. It’s a city of shadows and gin-soaked clubs.

Second, pay attention to the dialogue. Dobbs has an incredible ear for how politicians use language to avoid saying anything at all.

Third, look for the differences in the Mattie Storin character. She’s much more than a victim; she’s a mirror for Urquhart’s own ambition.

Actionable Next Steps for Fans

- Track down the original 1989 edition: Some later versions were edited to align more with the TV show’s tone. The original is the rawest version of the story.

- Compare the "Chief Whip" roles: Research what a Chief Whip actually does in the UK Parliament versus the US Congress. It explains why Urquhart had so much more leverage than Frank Underwood did initially.

- Read the sequels: Dobbs wrote To Play the King and The Final Cut. They aren't as tight as the first book, but they complete the arc in a way the Netflix show never quite managed to do effectively.

- Watch the 1990 BBC version: It’s only four episodes. It’s the closest adaptation to the book's spirit, and Ian Richardson’s performance is arguably superior to Spacey’s because of its understated malice.

The House of Cards novel remains a cornerstone of political fiction for a reason. It isn't about policy. It isn't about parties. It’s about the dark, uncomfortable reality that some people just want to win, and they don't care who gets hurt in the process. It’s a quick read, but it’s a heavy one.

To truly understand the DNA of modern political drama, you have to go back to the source. Start with the first chapter. Pay attention to how Urquhart looks at the photograph of his rivals. That’s where the real story begins.

Next Steps for Deep Research:

- Compare the endings: Look up the "rooftop scene" variations across the book, the UK show, and the US show. Each reflects the era's cultural attitude toward justice.

- Author Context: Read Michael Dobbs' interviews about his time with Margaret Thatcher to see which real-life politicians inspired the characters in the book.

- Literary Analysis: Examine the recurring motif of "The House of Cards" as a metaphor for the British Parliamentary system’s reliance on tradition over transparency.