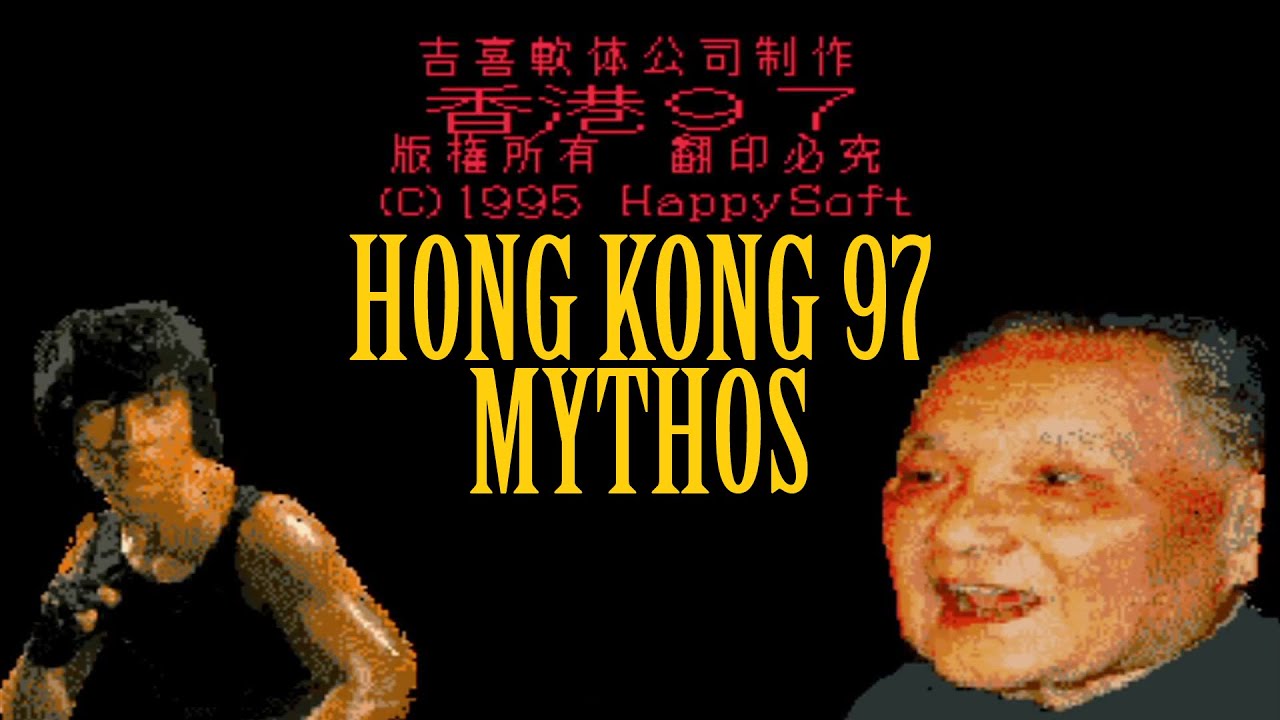

Video games usually try to keep you playing. They want you to feel heroic, or at the very least, entertained. But then there is Hong Kong 97. If you’ve spent any time in the darker corners of the retro gaming community, you’ve probably seen it. It’s a grainy, low-resolution image of a human corpse, riddled with what look like bullet wounds. It pops up the second you lose, accompanied by a looping, high-pitched snippet of Chinese pop music that drills into your skull.

The Hong Kong 97 death screen isn’t just a "game over" message. It’s a piece of digital trauma.

For years, people thought it was a fake. Or a creepypasta. But it’s very real. The game was developed in 1995 by Yoshihisa "KOWLOON" Kurosawa, a Japanese journalist who basically wanted to make the worst, most offensive game possible as a middle finger to the gaming industry. He succeeded. He actually managed to get these cartridges produced and sold them via mail order, though very few copies ever actually made it into the wild. The game is functionally unplayable—a chaotic "shoot-em-up" where you control a likeness of Jackie Chan (renamed Chin) and murder waves of people ahead of the 1997 handover of Hong Kong.

But the death screen is what stuck. It's the part that feels "illegal" to look at.

The grim reality behind the image

Most games use pixels for gore. This game used a photograph.

For over two decades, the identity of the man in the Hong Kong 97 death screen was the subject of intense, often macabre speculation. Was it a victim of the Bosnian War? A photo from a medical textbook? Some even suggested it was a real-life victim of a celebrity assassination. The truth, which finally surfaced around 2019-2020 thanks to dedicated internet sleuths on platforms like Reddit and specialized gaming forums, is a bit more bureaucratic but no less grim.

The image is actually a still from a documentary or news reel regarding the death of a Polish citizen named Leszek Błażyński. He was a successful boxer, a bronze medalist in the Olympics. It’s a tragic story. He took his own life in 1992. The image used in the game was a low-quality capture of his body taken from a Polish television broadcast or a forensic archive that found its way into a Japanese "shock" magazine.

Kurosawa has admitted in interviews, specifically with South China Morning Post, that he just grabbed images from magazines and news broadcasts without a second thought. He was young. He was reckless. He didn't care about copyright, and he certainly didn't care about the ethics of using a real person's tragic end as a "Game Over" screen for a joke project.

💡 You might also like: Thinking game streaming: Why watching people solve puzzles is actually taking over Twitch

It’s easy to forget how much of a "Wild West" the early 90s were for digital media. You could find almost anything in the back-alley shops of Akihabara.

Why it still creeps us out today

There is something called the "Uncanny Valley," but this is something else entirely. It’s the "Mondo" aesthetic.

In the 90s, there was a weird subculture of "shock" media—think Faces of Death or https://www.google.com/search?q=Rotten.com. The Hong Kong 97 death screen is a direct descendant of that era. When you play a modern game like Call of Duty, the graphics are incredible, but you know it’s math. It’s code. When you see that grainy, 16-bit compressed photo of a real person in Hong Kong 97, your brain reacts differently. You know you’re looking at a human being who once breathed.

The contrast is what makes it peak nightmare fuel.

- The music. It's a five-second loop of "I Love Beijing Tiananmen." It never stops.

- The gameplay. It's mindless, repetitive, and ugly.

- The suddenness. There is no fade to black. You die, and bam—corpse.

Honestly, it’s the lack of context that makes it work as a piece of accidental horror. Without the internet to explain it, kids who stumbled upon this via emulators in the early 2000s were left to their own imaginations. That’s how urban legends start.

The technical "how" of the horror

The game was designed for the Super Famicom (the Japanese SNES), but it wasn't a licensed Nintendo product. Not even close. It was meant to be played using a "Magicicom" device—a copier that allowed the SNES to run games from floppy disks.

Because it was running on a floppy disk system, it had slightly more freedom with file sizes for static images than a standard 1995 cartridge might have, though the quality is still abysmal. The programmer, who Kurosawa claims was an employee at a "legit" game company working under a pseudonym to avoid getting fired, basically slapped a JPEG-style compression on a scanned photo and called it a day.

📖 Related: Why 4 in a row online 2 player Games Still Hook Us After 50 Years

The result? A pixelated, discolored mess that actually looks scarier than the original photo because your mind fills in the blurry details.

Misconceptions about the game's intent

People often try to find deep political meaning in Hong Kong 97. They think it’s a profound commentary on the tension between China and Britain.

It isn't.

Kurosawa has been pretty blunt about this. He wanted to make something "vulgar." He thought the gaming industry was too "proper" and boring. He made the game in two days. Two days! Most of that time was probably spent drinking or trying to get the code to not crash. The Hong Kong 97 death screen wasn't a curated choice meant to evoke a specific emotion; it was just the most shocking thing he had on hand.

It's sort of the "punk rock" of video games, but without the talent. It’s just noise.

The aftermath and Kurosawa's regret

In recent years, Kurosawa has expressed a mix of amusement and genuine annoyance that this is his legacy. He’s a travel writer now. He’s done interesting things. Yet, every few months, someone tracks him down to ask about the "corpse game."

He's asked people to stop playing it. Not because it's cursed, but because he thinks it's a piece of junk. But that’s the thing about the internet—once something is identified as "cursed," it lives forever. You can’t delete a nightmare.

👉 See also: Lust Academy Season 1: Why This Visual Novel Actually Works

What we can learn from this weird relic

Looking back at the Hong Kong 97 death screen tells us a lot about how our relationship with digital media has changed. Today, if a developer put a real photo of a deceased person in a game, it would be scrubbed from the internet in hours. There would be lawsuits. There would be massive social media outcries.

In 1995? It just sat on a floppy disk in a dusty shop in Hong Kong, waiting for someone to find it.

If you’re interested in the history of "kusoge" (crap games), this is the undisputed king. But if you're looking for the death screen itself, maybe just... don't. Or at least, do it with the sound off. That song will stay with you for weeks.

To understand the full scope of this weirdness, you really have to look at the community that tracked down the source image. It took years of cross-referencing obscure Japanese magazines and Polish television archives. It's a testament to how the internet can solve almost any mystery, even one as niche as "who is the guy on the game over screen of a 30-year-old bootleg?"

The next steps for the curious:

If you want to dive deeper into this rabbit hole without losing your mind, start by reading the 2018 interview with Yoshihisa Kurosawa in the South China Morning Post. It de-mythologizes the game and makes it much less "scary" and much more "pathetic." After that, look up the "archival" threads on the Assemblergames forums (now archived) to see the step-by-step process of how the image was identified. It’s a fascinating look at digital forensics. Just remember: it’s a game made to be hated. Don’t give it more power than it deserves.