If you want to see Sean Connery actually act—I mean, really strip away the Bond tuxedo and show the sweat and the rage underneath—you have to watch Sidney Lumet’s 1965 masterpiece. Honestly, The Hill movie 1965 is a bit of a nightmare. It’s loud. It’s dusty. It’s claustrophobic despite being set in the wide-open Libyan desert. Most modern war movies try to be "gritty" by using shaky cams or excessive gore, but Lumet didn't need any of that. He just needed a pile of sand and the sound of men screaming.

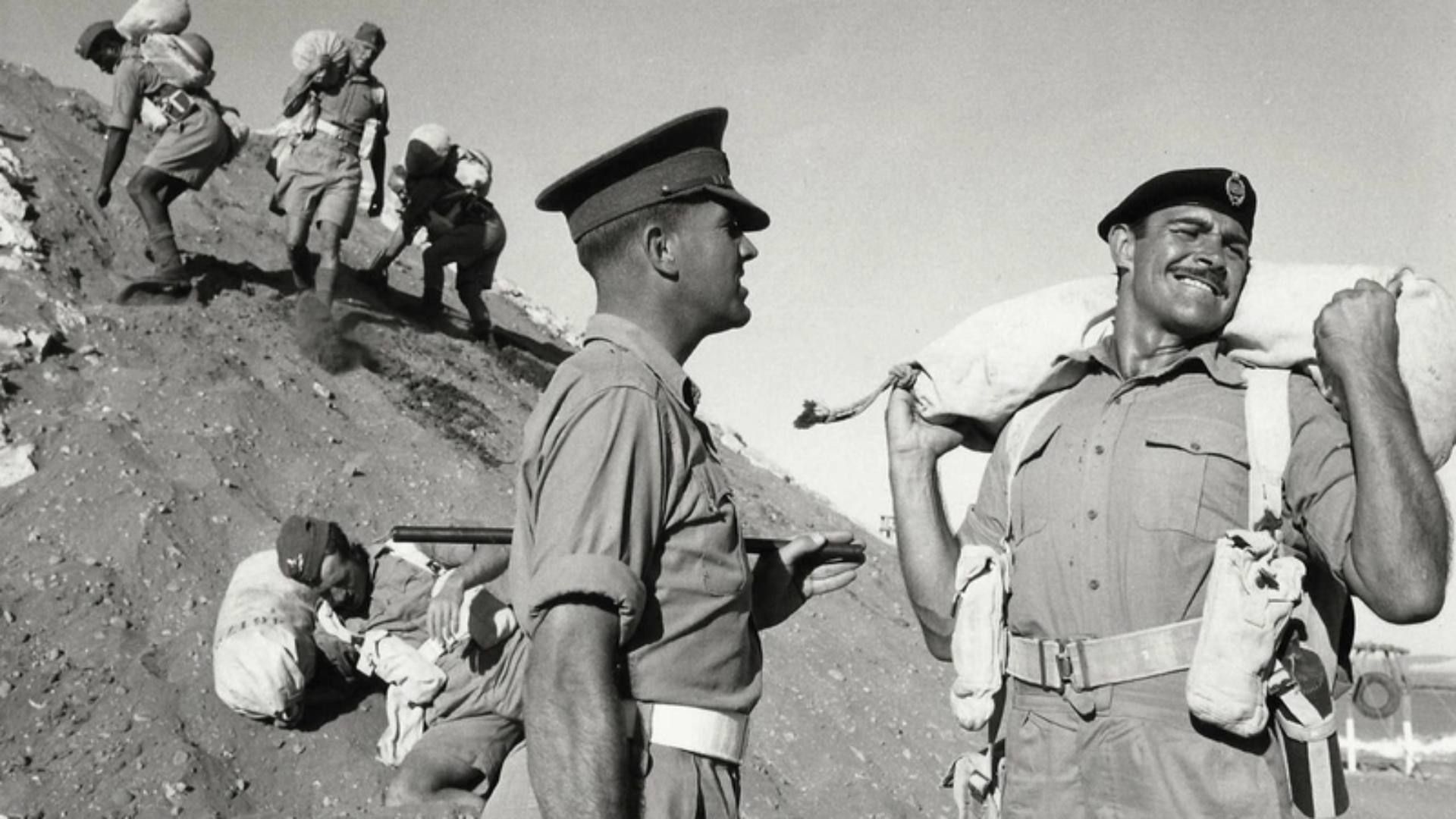

It’s basically a movie about a British Army detention camp during World War II. But it’s not a "war movie" in the sense of soldiers fighting a foreign enemy. No, this is about the military machine eating its own. The "Hill" isn't a natural landmark; it’s a man-made mound of sand and rock, built by the prisoners, meant for nothing but the systematic breaking of the human spirit.

The Brutality of the Hill Explained

The premise is deceptively simple. Five new prisoners arrive at the camp. They’ve been sent there for various "crimes"—desertion, theft, punching an officer. Among them is Joe Roberts, played by Connery, a former Sergeant Major who refused to lead his men into a suicidal massacre. He’s the moral center, but he’s also a man who has completely lost faith in the hierarchy he once served.

The camp is run by the sadistic Staff Sergeant Williams (Ian Hendry), a man who gets a genuine, twisted thrill out of watching men collapse. He forces them to climb "the hill" over and over again in the blistering heat. Up and down. Up and down. Under the full sun. With full packs. There is no strategic purpose to this. It’s pure, unadulterated punishment designed to hollow out a person until there’s nothing left but obedience.

What most people get wrong about this film is thinking it's a simple "hero vs. villain" story. It’s much more cynical than that. The Regimental Sergeant Major, Wilson (Harry Andrews), isn't necessarily a "bad" man in his own mind. He’s a bureaucrat of pain. He believes in the system. He believes that the Hill is necessary to maintain discipline in an army that is currently fighting for the survival of the Western world. That’s the terrifying part. He’s not a monster; he’s a professional.

Why the Cinematography Feels Like a Fever Dream

Sidney Lumet and cinematographer Oswald Morris did something crazy with the cameras here. They used wide-angle lenses—specifically the 18mm and 24mm—and shoved them right into the actors' faces. You see every bead of sweat. Every cracked lip. Every dilated pupil. It’s uncomfortable to watch. It makes you feel like you’re trapped in that heat with them.

📖 Related: Big Brother 27 Morgan: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

The sound design is another beast entirely. There is no musical score. None. Zero. You just hear the rhythmic crunch of boots on sand, the whistling wind, and the constant, barking shouts of the NCOs. It creates this relentless, pounding atmosphere that mimics the exhaustion of the characters. By the time the movie hits the halfway mark, you’re basically as tired as the prisoners are.

The Performance That Redefined Sean Connery

In 1965, Connery was the biggest star in the world because of Goldfinger and Thunderball. He could have spent his whole career sipping martinis on screen. But he fought to make The Hill movie 1965 because he wanted to prove he had range. And man, does he.

He’s bulky, hairy, and perpetually angry. When he looks at Williams with that "I will kill you if I get the chance" stare, you believe it. But it’s the quiet moments—where he tries to keep his fellow prisoners from losing their minds—where you see the nuance. He’s playing a leader who has seen the worst of humanity and is trying to decide if it’s still worth being "good."

The supporting cast is equally legendary. Ossie Davis plays Jacko King, a West Indian soldier who has to deal with the camp’s brutality on top of the systemic racism of the 1940s British military. His performance is a powerhouse of dignity under fire. Then there’s Ian Bannen as the "sympathetic" guard, Harris. He’s the guy who knows what they’re doing is wrong but is too weak to stop it. That might be the most relatable, and therefore the most tragic, character in the whole film.

The Psychological Toll of the "System"

The movie is a blistering critique of authority. It’s not just about one bad camp; it’s about how systems protect themselves. When a prisoner eventually dies from the mistreatment, the reaction of the "higher-ups" isn't horror. It’s a scramble to cover their backs. They don't care that a man is dead; they care that the paperwork looks right.

👉 See also: The Lil Wayne Tracklist for Tha Carter 3: What Most People Get Wrong

This is why the film still matters. It’s a universal story about how power corrupts and how easily "following orders" becomes an excuse for atrocity. It’s a precursor to movies like Full Metal Jacket or A Few Good Men, but it’s arguably much bleaker. There is no triumphant courtroom scene here. There is only the heat and the sand.

What Happened During Production

The making of the movie was almost as tough as the story itself. They filmed in Almería, Spain, during a massive heatwave. Temperatures regularly topped 110 degrees. The crew was miserable. The actors were actually exhausted. Lumet apparently told the cast that if they weren't sweating for real, they weren't doing their jobs.

Connery reportedly did many of those hill climbs himself. No stunt doubles for the "Bond" of the era. He wanted the physical reality of the exhaustion to show in his body language. You can't fake that kind of heavy breathing or the way his legs start to shake toward the end of the film. It’s raw.

Is The Hill Based on a True Story?

Sort of. It was based on a play by Ray Rigby, who had actually spent time in a British military prison in North Africa during the war. While the specific characters are fictionalized, the "Hill" was a real thing. These camps existed. The British called them "Glasshouses." They were designed to be so miserable that a soldier would rather face German machine guns on the front lines than spend another day in detention.

Rigby’s script captures the specific slang and the rigid, almost theatrical nature of military discipline. It’s incredibly authentic. If the dialogue feels fast and overlapping, that’s because Lumet wanted it to feel like real life, not a polished Hollywood production.

✨ Don't miss: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

Why This Film is Often Overlooked

It’s black and white. It’s British. It’s incredibly depressing. These aren't exactly the ingredients for a summer blockbuster. In 1965, audiences wanted the glamour of The Sound of Music or the gadgetry of Bond. The Hill movie 1965 was a hard sell. It didn't make a ton of money at the box office, and it’s often skipped over in "Best War Movie" lists because it lacks the big explosions.

But for cinephiles, it’s a masterclass. It’s a movie that demands your full attention. You can’t scroll on your phone while watching this; the tension is so thick that if you look away, you’ll feel like you’ve missed a beat of a heart attack. It’s a film that stays with you. You’ll find yourself thinking about that final, chaotic scene for days afterward.

Key Takeaways for Viewers

If you’re going to sit down and watch this, keep a few things in mind. First, pay attention to the blocking. Lumet was a theater guy, and the way he moves the actors around the confined spaces of the barracks is brilliant. Second, watch the power dynamics. Notice how they shift whenever a superior officer enters the room. Everyone is terrified of the person one rung above them.

- Check the Lenses: See how the faces look distorted in close-ups? That’s intentional. It’s meant to make everyone look slightly monstrous.

- Listen to the Silence: Notice how the lack of music makes the violence feel more "real" and less "cinematic."

- Focus on Jacko King: Ossie Davis gives a performance that was decades ahead of its time in terms of how it handled race and defiance.

How to Experience The Hill Today

You can usually find the film on specialized streaming services like Criterion Channel or for rent on major platforms. It’s best watched on the biggest screen possible to truly appreciate the scale of the desert and the intensity of the close-ups.

If you’re a fan of Sean Connery, this is essential viewing. It’s the bridge between his early "hunk" roles and his later "venerable elder" roles like in The Untouchables. It shows he was a powerhouse actor from the very beginning, willing to get dirty and ugly for the sake of a story.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Watch the movie without distractions. This isn't a "background" film. Turn off the lights and let the oppressive atmosphere take over.

- Compare it to Lumet’s other work. If you like the intensity here, watch 12 Angry Men or Network. You’ll see the same fascination with how groups of people handle pressure and moral dilemmas.

- Research the "Glasshouses." Looking into the history of British military prisons adds a layer of horrifying context to the film.

- Pay attention to the ending. It is one of the most abrupt and jarring endings in cinema history. Don’t expect a neat resolution; expect a gut punch.