You’re barely out of the delivery room, exhausted and probably still processing the fact that you’ve actually brought a tiny human into the world, when a nurse mentions the first shot. It’s the hepatitis B vaccine for babies, and for many parents, the timing feels weirdly aggressive. Why does a newborn—someone who isn't sharing needles or having unprotected sex—need a vaccine for a blood-borne virus before they’ve even had their first diaper change?

It’s a fair question.

Honestly, the logic behind the "birth dose" isn't about what your baby is doing today. It’s about the terrifying efficiency of the Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and a biological loophole in an infant's developing immune system. When an adult catches Hep B, their body usually fights it off. They might get sick, feel like garbage for a month, and then they're immune. But when a baby catches it? Their immune system doesn't even recognize the virus as an enemy. It just lets it move in and set up shop.

The 90 Percent Problem Nobody Mentions

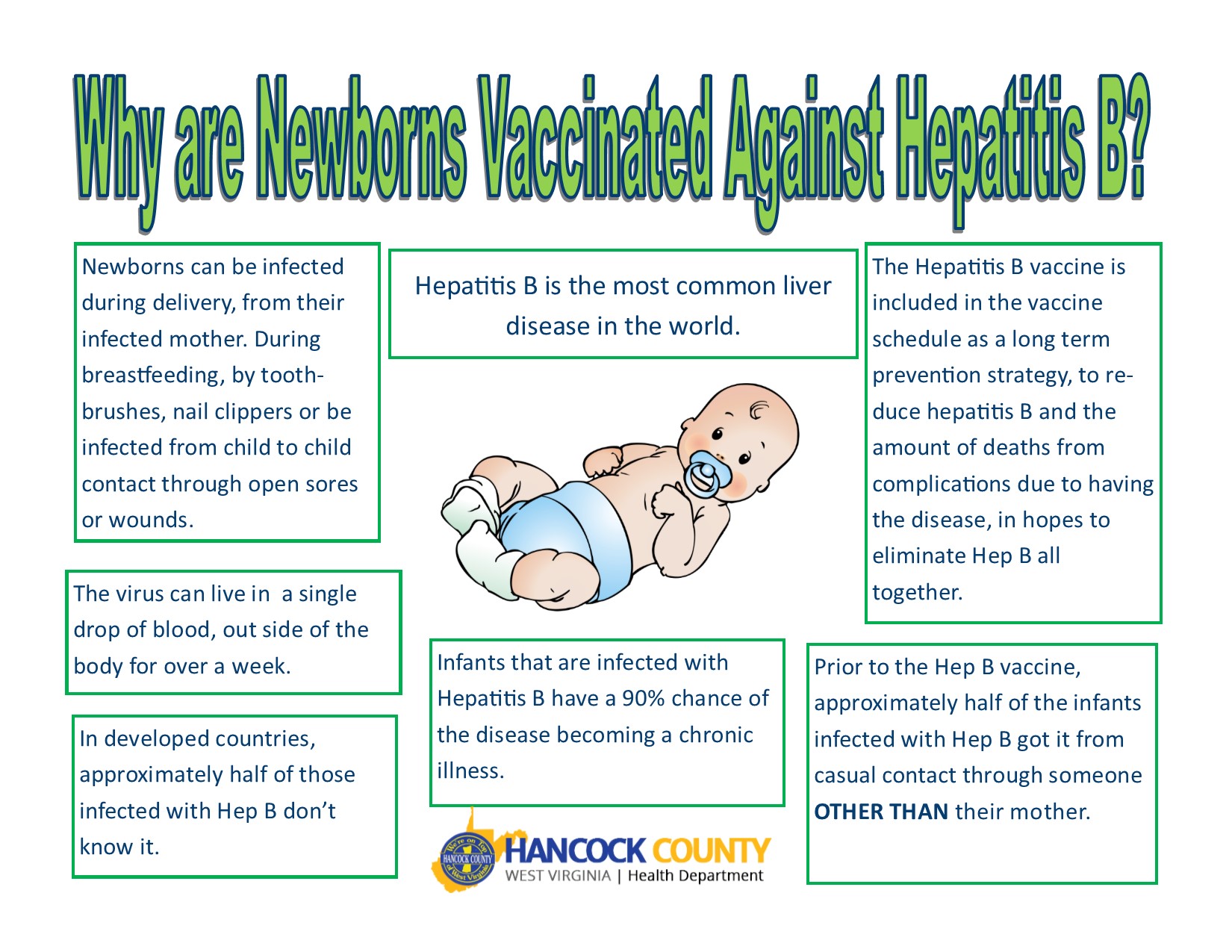

If a baby is exposed to Hepatitis B during birth or in early infancy, there is a 90% chance that infection becomes chronic. Permanent. A lifelong companion that slowly scars the liver.

🔗 Read more: Is it harmful to drink too much water? The truth about overhydration

Compare that to adults, where only about 5% of infections become chronic.

The virus is incredibly hardy. It can live on a surface—a toothbrush, a toy, a countertop—for seven days. It’s significantly more infectious than HIV. While we like to think our "bubble" is safe, we don't always know who is carrying the virus. Many people have chronic Hep B and don't even know it because they have zero symptoms for decades until their liver starts failing. This is why the hepatitis B vaccine for babies is administered so early; it’s about closing the window of vulnerability before it ever opens.

How the vaccine actually works in that tiny body

The vaccine isn't a live virus. You can't "get" Hep B from the shot. It’s basically just a tiny piece of the virus’s outer coat (the surface antigen). Think of it like showing your baby's immune system a picture of a "Wanted" poster. The body sees the protein, realizes it doesn't belong there, and starts building a library of antibodies.

Most infants get a series of three or four doses. The first happens within 24 hours of birth. The second usually comes at the one or two-month mark. The final dose is typically given between 6 and 18 months.

By the time they've finished the series, more than 95% of infants are protected for at least 30 years, and likely for life. It is, quite literally, one of the most effective vaccines we have ever engineered.

What happens if you skip the birth dose?

Some parents ask if they can just wait until the two-month checkup. "We're staying home anyway," is the common refrain.

But here’s the catch.

Labor is messy. Even if a mother tests negative for Hep B during pregnancy, those tests aren't 100% foolproof. There are cases where a mother acquires the infection late in the third trimester after her initial screening. If the baby isn't vaccinated at birth and the mother is unknowingly positive, the window to prevent a chronic infection slams shut.

Also, family dynamics are unpredictable. A visiting relative, a childcare provider, or even a sibling could be a carrier. If a baby with an unvaccinated immune system comes into contact with even a microscopic amount of infected blood—perhaps from a scraped knee or a shared personal item—the risk is astronomical.

Dr. Sarah Long, a prominent member of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), has often pointed out that the birth dose is a "safety net" for the failures of the healthcare system. It ensures that even if a lab result is lost or a mother's status is miscoded, the baby is safe.

Addressing the "Too Much, Too Soon" Anxiety

It's natural to look at a seven-pound baby and wonder if their system can handle a vaccine.

The math, however, is reassuring.

Every day, your baby’s immune system is bombarded by thousands of antigens. The dust in the air, the bacteria on your skin, the proteins in their milk—all of these "challenge" the immune system. The hepatitis B vaccine for babies contains just one single antigen. It is a microscopic drop in the bucket compared to what a baby handles just by breathing in a normal living room.

Common side effects (The real ones)

Most babies just sleep a bit more or have a slightly sore leg.

- Fever: Occurs in about 1% to 6% of infants. It's usually mild.

- Redness: A little bit of swelling at the injection site is common.

- Fussiness: Because, well, they just got a shot.

Severe allergic reactions are incredibly rare, occurring in about one per 1.1 million doses. When you weigh that against the reality of liver cancer or cirrhosis later in life, the math starts to look very different.

The Global Perspective on Liver Cancer

We often forget that Hepatitis B is the leading cause of liver cancer worldwide. In countries where the hepatitis B vaccine for babies was implemented decades ago, the rates of childhood liver cancer have plummeted.

Take Taiwan, for example. Before they started universal infant vaccination in 1984, the rate of chronic infection in children was over 10%. After the program started? It dropped to less than 1%. They didn't just stop a virus; they effectively cured a generation of a specific type of cancer.

✨ Don't miss: What Cannot Be Mixed With Turmeric: Why Your Golden Milk Might Be Backfiring

Myths that just won't die

You've probably heard the one about thimerosal (mercury).

Let's clear that up: Since 2001, none of the Hep B vaccines used for routine infant vaccination in the U.S. contain thimerosal. They are preservative-free.

Then there's the argument that "it's an STD, so my baby isn't at risk." Again, this ignores the reality of how long the virus survives on surfaces. It also ignores the long game. You aren't just vaccinating a baby; you're vaccinating the adult they will become. By the time they are teenagers and young adults—when risks for exposure naturally increase—they will already have a fortress of immunity built. You're giving them a gift they won't even realize they have.

Navigating the Schedule

Sometimes the schedule feels like a lot of appointments.

In the U.S., many doctors use "combination vaccines." This means your baby might get the Hep B vaccine as part of a single shot that also covers DTaP (diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis) and Polio (IPV). This is great because it means fewer pokes for the baby and less stress for you.

If your baby was born prematurely or with a low birth weight (less than 2,000 grams), the timing might shift slightly. Usually, if the mother is negative, doctors might wait until the baby is one month old or being discharged from the hospital, because the vaccine is slightly more effective once the baby has put on some weight. However, if the mother is positive or her status is unknown, that baby gets the shot immediately, regardless of weight. No exceptions.

Actionable Steps for Parents

It's easy to get lost in the sea of medical jargon. If you're preparing for a birth or have a newborn, here is the straightforward path:

1. Verify your own status. Double-check your prenatal records to ensure you were screened for HBsAg (Hepatitis B surface antigen). Knowing your status is the first line of defense.

📖 Related: Why Good Food for Hangover Relief Actually Works According to Science

2. Talk to your pediatrician before delivery. Don't wait until you're in the hospital. Ask them which brand of vaccine they use and if they use combination shots later on. This removes the "surprise" factor in the recovery room.

3. Keep the immunization record handy. You'll need this for daycare and school later. Most offices use digital portals now, but having a physical or digital copy on your phone is a lifesaver.

4. Watch for the right signs. After the shot, if your baby has a fever over 100.4°F or seems unusually lethargic, call the doc. It’s probably nothing, but peace of mind is worth the phone call.

5. Complete the series. This is the big one. One shot offers some protection, but the second and third doses are what lock that immunity in for the long haul. Mark the two-month and six-month appointments on your calendar in permanent ink.

Protecting a child from a silent, chronic liver disease is one of the few "wins" in parenting that is almost entirely within your control. It’s a bit of a sting early on, sure, but it beats the alternative of a lifetime of medical monitoring. We live in an era where we can actually prevent cancer with a simple series of shots starting on day one. That’s pretty incredible when you think about it.