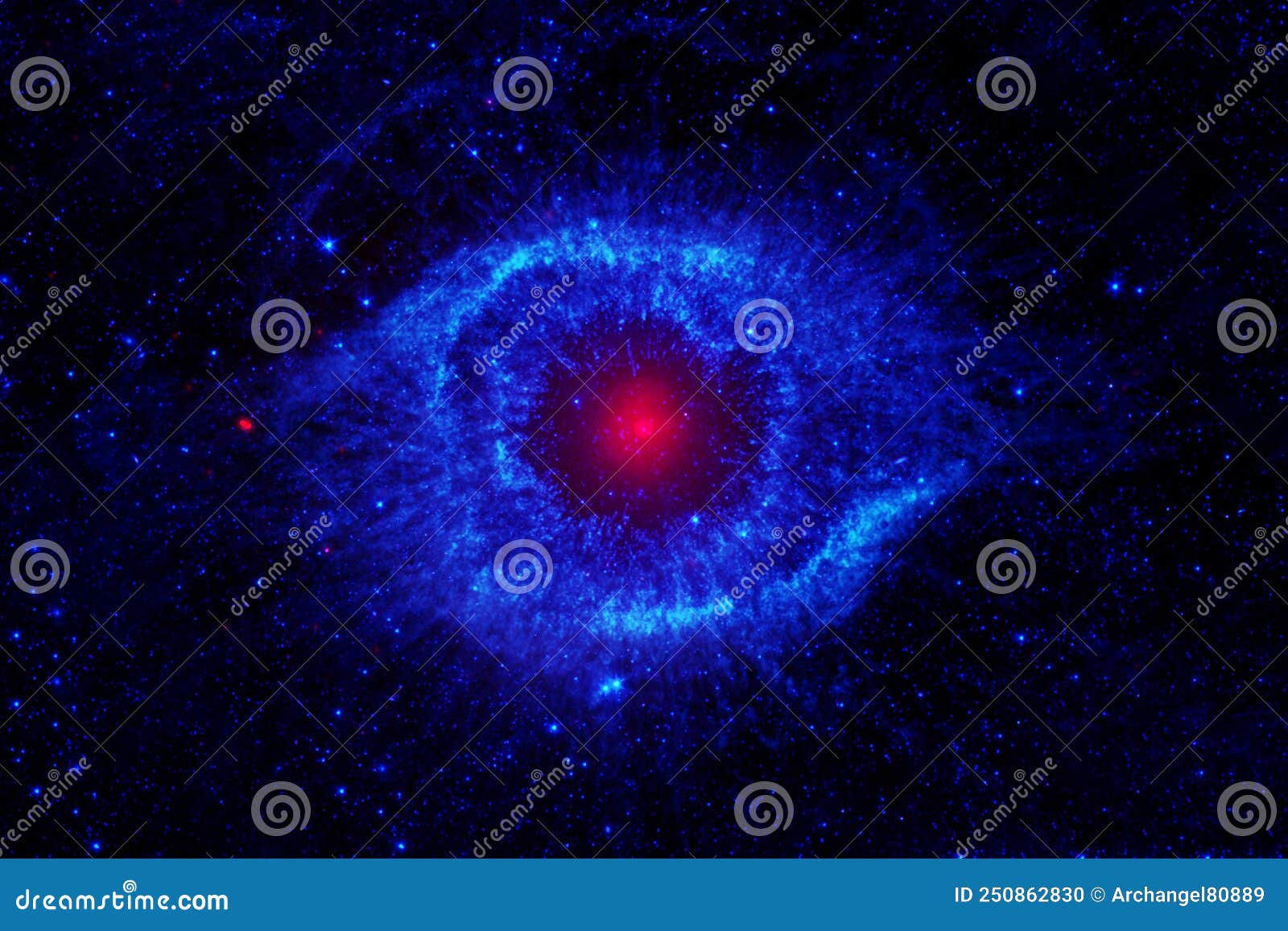

You’ve seen the photo. It’s that haunting, deep blue iris surrounded by fleshy pink lids, staring back at you from the void of space like the eye of a god. Most people call it the Eye of God, but astronomers know it as the Helix Nebula, or NGC 7293. It’s arguably the most famous planetary nebula in the sky, and honestly, it’s one of the best examples of what happens when a star decides to pack it in and call it a day.

Space is big. Like, really big. But the Helix is relatively close, sitting just about 650 light-years away in the constellation of Aquarius. That proximity is exactly why it looks so detailed in those famous Hubble shots.

What the Helix Nebula Actually Is (and Isn't)

Despite the name, a planetary nebula has nothing to do with planets. Early astronomers like William Herschel saw these round, fuzzy objects through low-power telescopes and thought they looked like the discs of Uranus or Neptune. The name stuck, even though we now know these are actually the "shroud" of a dying star.

The star at the center of the Helix used to be a lot like our Sun. Then it ran out of fuel. When a star like ours dies, it doesn't go out with a bang (that's for the massive ones). Instead, it goes through a slow, messy divorce with its outer layers. It puffs up into a red giant, then sheds its skin in a series of violent pulses. What we’re seeing as "the eye" is actually a complex tunnel of glowing gas and dust.

We’re basically looking down the barrel of a trillion-mile-long cylinder.

Imagine a donut. If you look at it from the side, it's just a flat line. But if you look through the hole, you see a ring. That’s what’s happening here. The "pupil" is the hot, dense core of the star—a white dwarf—flooding the surrounding gas with intense ultraviolet light. This light makes the gas glow, creating those vivid reds from nitrogen and hydrogen and the eerie blues from oxygen.

The Cometary Knots: Those Weird Streaks in the Eye

If you zoom in on the inner rim of the "iris," you’ll see thousands of tiny, tadpole-shaped streaks. Astronomers call these cometary knots. They aren't actually comets, though. Each one is a clump of cool gas and dust, about the size of our entire solar system, with a tail stretching back for miles.

C. Robert O'Dell and his team at Vanderbilt University have spent years studying these things. They’re formed when a fast "wind" of gas from the central star slams into slower, older material. It’s fluid dynamics on a galactic scale. It’s messy. It’s beautiful. It’s also a preview of what might happen to the gas surrounding our own Sun in about five billion years.

Seeing the Eye for Yourself

You don't need a multi-billion dollar space telescope to find it, but don't expect it to look like the posters. In a small backyard telescope, the Helix Nebula is notoriously "shy." It has a large angular size—about half the size of the full moon—but its light is spread out. This makes it very faint.

To see it, you need a truly dark sky. No city lights. No moon. You’ll also want a "nebula filter" (an OIII or UHC filter), which blocks out most light except for the specific wavelengths emitted by the glowing gas. Through the eyepiece, it won’t look colorful; it’ll look like a ghostly, greyish smoke ring hanging in the dark.

Best times to look:

- Late Summer/Early Autumn: This is when Aquarius is highest in the sky for Northern Hemisphere observers.

- Southern Hemisphere: You actually have the best seat in the house. From places like Australia or Chile, the Helix passes almost directly overhead, meaning you're looking through much less of Earth's distorting atmosphere.

Why It Matters Beyond the "Cool" Factor

The Helix Nebula is a laboratory. Because it's so close, we can use it to test our theories on how chemical elements are recycled back into the universe. The carbon and oxygen being blown off that star right now will eventually drift into giant molecular clouds. Billions of years from now, that same dust might collapse to form a new star, and maybe even new planets.

It’s the ultimate recycling program.

📖 Related: Oracle Class Action Lawsuit Explained: What Really Happened and Where the Money Went

We also use the Helix to study "photo-evaporation." The central white dwarf is incredibly hot—around 120,000 degrees Celsius. This heat is literally eroding the clumps of gas from the inside out. By measuring how fast those cometary knots are disappearing, we get a better handle on how long these nebulae last. Turns out, they’re short-lived in cosmic terms. The "eye" will likely dissipate and vanish within 10,000 years, leaving only a tiny, cooling white dwarf behind.

Common Misconceptions

People often get the Helix Nebula confused with the Ring Nebula (M57) or the Cat's Eye Nebula. While they are all planetary nebulae, the Ring is much smaller and further away, and the Cat's Eye is significantly more structurally complex (and looks more like a psychedelic seashell than an eye).

Also, the "colors" in the photos aren't "fake," but they aren't exactly what you'd see with the naked eye either. Cameras can do something human eyes can't: they can collect light for hours. Most of the iconic "Eye of God" images are composites of different wavelengths, including infrared data from the Spitzer Space Telescope, which shows the cooler dust that our eyes simply can't detect.

How to Start Your Own Observation

If you're serious about seeing the "eye" that looks back from space, start with these steps:

🔗 Read more: How to download albums from Spotify for offline listening without the headache

- Download a Star Map App: Use something like Stellarium or SkySafari to find the exact coordinates of NGC 7293 in the constellation Aquarius.

- Invest in 10x50 Binoculars: If your sky is dark enough, you can actually see the nebula as a tiny, fuzzy patch through decent binoculars. It's a great way to "scout" the location before moving to a telescope.

- Use Averted Vision: When looking through a telescope, don't stare directly at the nebula. Look slightly to the side of it. The periphery of your retina is more sensitive to low light and will help the "eye" pop out of the background.

- Check the "Bortle Scale": Before you drive out to the desert, check a light pollution map. You want a site that is at least a Bortle 3 or 4. If you're in a Bortle 8 (inner city), you're basically wasting your time trying to see the Helix.

The Helix Nebula reminds us that even stars have a lifespan. It’s a spectacular, somewhat haunting exit for a sun that lived for billions of years. While it looks like an eye watching over us, it's really just physics and chemistry playing out on a scale so massive it’s hard to wrap your head around. But hey, that’s half the fun of looking up.