It is the kind of story that sounds like a bad bar joke or a glitch in a flight simulator, but it actually happened. On September 21, 1956, a test pilot named Thomas W. Attridge Jr. was pushing a brand-new Grumman F-11 Tiger through its paces over the Atlantic. He fired a four-second burst from his 20mm cannons while in a shallow dive. Then, he accelerated. He went into a steeper dive, and less than a minute later, his windshield shattered and his engine began to shred itself.

He hadn't been hit by enemy fire. There wasn't anyone else in the sky. Attridge had literally overtaken his own bullets. The Grumman F-11 Tiger was so fast, and its trajectory so specific, that it caught up to the decelerating rounds and flew right into them.

That incident basically sums up the F-11's entire existence: brilliant, incredibly fast, and somehow always running into its own problems. It was a beautiful machine, arguably one of the sleekest jets ever to catch a wire on a carrier deck, but it was also a victim of the most ruthless era of aviation development in history.

The Design That Changed Everything (Quietly)

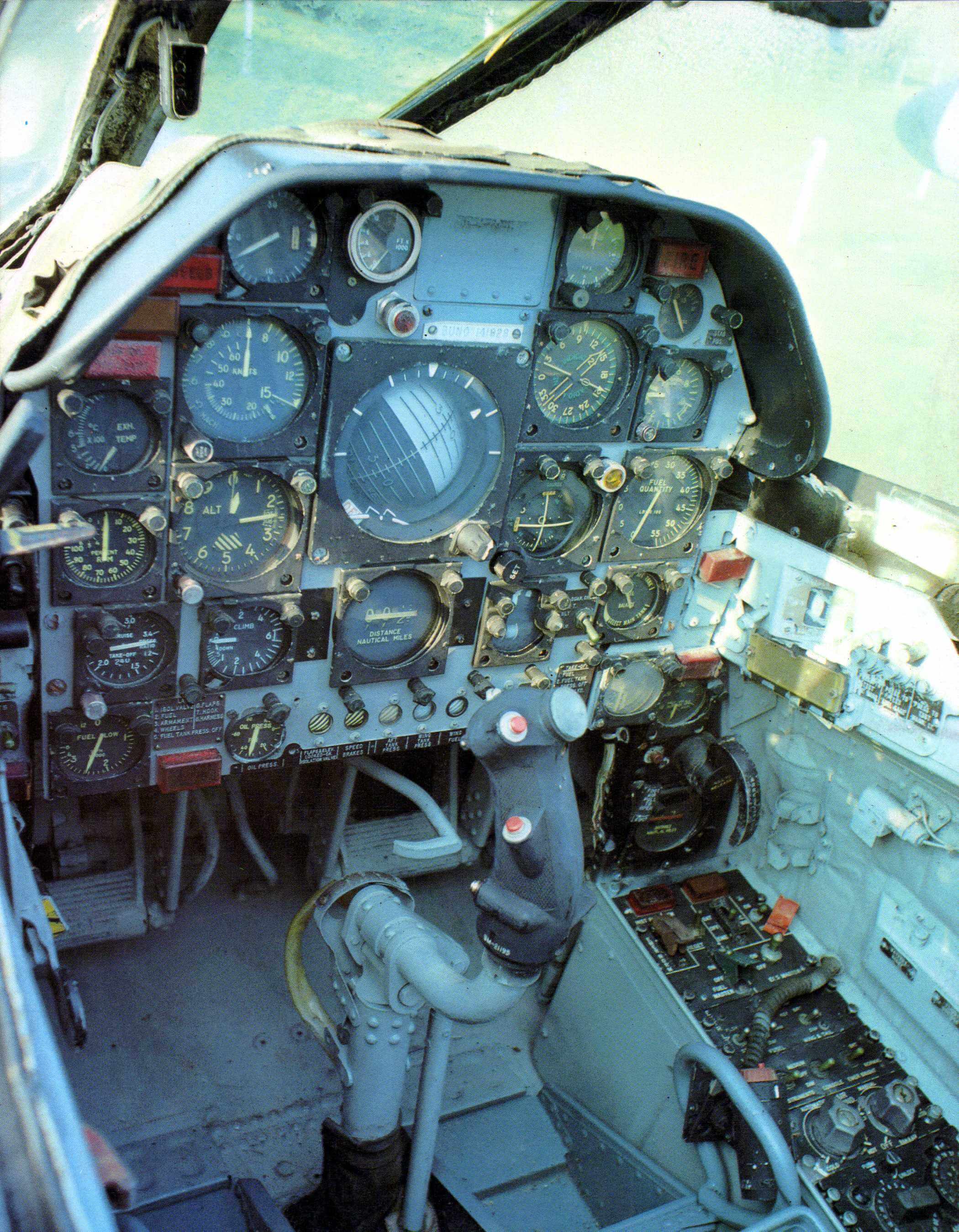

When you look at the Tiger, you’re looking at the first real application of "Area Rule" in a Navy fighter. Back in the early 50s, engineers were hitting a literal wall. They called it the sound barrier, but it felt more like a physical obstacle. Planes would buffet, shake, and refuse to go any faster regardless of how much thrust you shoved behind them.

Richard Whitcomb, a legendary NACA engineer, figured out that if you pinched the fuselage in the middle—kind of like a Coke bottle or a wasp’s waist—you could drastically reduce transonic drag. Grumman took this idea and ran with it. The Grumman F-11 Tiger ended up with this distinctive, slender midsection that allowed it to slip through the air with a grace its predecessors, like the F9F Cougar, simply couldn't match.

It was light. It was nimble.

Because the Tiger didn't have the massive weight of the dual-engine setups seen in later Phantoms, it handled like a dream. Pilots loved the way it felt. It wasn't just a weapon; it was a sports car with wings. However, that lightness came at a cost that eventually bit the Navy in the backside.

👉 See also: Frontier Mail Powered by Yahoo: Why Your Login Just Changed

The Engine Problem Nobody Could Fix

You can have the best airframe in the world, but if the heart isn't right, the body fails. The Grumman F-11 Tiger was built around the Wright J65 turbojet. This was essentially a licensed version of the British Armstrong Siddeley Sapphire.

On paper? Great engine.

In reality? It was a nightmare for carrier operations.

The J65 was notoriously thirsty. The F-11 already had a limited internal fuel capacity because of that slim "Area Rule" fuselage we talked about. This meant the Tiger had the legs of a sprinter when the Navy needed a marathon runner. You’d launch, hit your targets or patrol your sector, and almost immediately have to look for a tanker or the carrier deck.

More importantly, the J65 wasn't reliable enough. It was prone to flameouts and didn't have the growth potential of the General Electric J79 engine that was being developed at the same time. While the Tiger was struggling with its fuel-hungry Wright engine, the F8U Crusader was hitting the scene with more power, more range, and more "oomph."

Why the Navy Moved On So Fast

The Tiger’s frontline career was blink-and-you-miss-it fast. It entered service in 1956 and was being pulled from frontline carrier squadrons by 1961. Five years. That’s it.

Most people think it was because the plane was "bad," but that’s not really true. It was just unlucky. It was caught in the "Supersonic Gap." Technology was moving so fast in the late 1950s that a plane could be state-of-the-art during its first flight and obsolete by the time it reached the fleet.

✨ Don't miss: Why Did Google Call My S25 Ultra an S22? The Real Reason Your New Phone Looks Old Online

- The Crusader was faster and carried more.

- The Phantom was on the horizon, promising two seats and radar.

- The Tiger lacked sophisticated all-weather radar capabilities.

Honestly, the Grumman F-11 Tiger was a daylight clear-air fighter in an era where the military was pivoting toward "all-weather" interceptors. If you couldn't find a Soviet bomber in a thick cloud bank using a radar screen, the Pentagon wasn't interested in buying thousands of you.

The Blue Angels and the Second Life

Even though the fleet gave up on the Tiger pretty quickly, the Blue Angels absolutely adored it. For them, the F-11’s flaws were actually features. Its responsiveness and crisp control made it perfect for tight, diamond formations.

They flew the Tiger from 1957 all the way until 1968. Think about that for a second. The plane spent twice as long as a showpiece for the Navy than it did as an actual combat-ready interceptor.

If you talk to aviation historians or former Blue Angel pilots like Bill Wheat, they’ll tell you the Tiger was the "sweetheart" of the team. It was small enough to be incredibly precise. When they eventually moved to the F-4 Phantom II, it was a massive culture shock. They went from a nimble fencing foil to a heavy sledgehammer.

The Technical Reality of Shooting Yourself Down

Let’s go back to Thomas Attridge for a moment, because people always get the physics wrong. They think the bullets slowed down and he "hit" them like a wall.

It’s actually more about the arc.

🔗 Read more: Brain Machine Interface: What Most People Get Wrong About Merging With Computers

The 20mm rounds leave the muzzle with a certain velocity. As soon as they hit the air, drag starts slowing them down. Because Attridge was in a dive and then increased his speed and deepened his dive, he essentially "cut the corner" of the bullets' ballistic trajectory. He flew a shorter path at a higher speed than the bullets were traveling along their curved path.

He didn't just hit one bullet. He was struck by several. One hit his engine's inlet guide vanes. Another hit the fan blades. He managed to limp the Grumman F-11 Tiger back toward the Grumman airfield in Bethpage, but the engine gave up the ghost just short of the runway. He crashed through the trees, broke some ribs, and survived—but the Tiger he was flying was a total loss.

It remains the only documented case of a pilot shooting himself down with a fixed-gun system in a jet fighter.

Legacy and What We Can Learn

The Grumman F-11 Tiger isn't a failure, even though its service life was short. It proved that Area Rule worked. it proved that Grumman could build a supersonic jet. It also served as a very expensive lesson in "future-proofing."

Today, you can still see Tigers in museums across the U.S., like the one at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola. They look like they're moving at Mach 1 even when they’re sitting on concrete.

Actionable Insights for History and Tech Buffs:

- Visit a Surviving Airframe: If you want to see the "Coke bottle" fuselage in person, the Pima Air & Space Museum in Arizona has a beautifully preserved F11F-1 (the later designation for the F-11).

- Study the Super Tiger: Look up the F11F-1F "Super Tiger." Grumman tried to save the program by putting a J79 engine in it. It actually broke world altitude and speed records, but the Navy still didn't buy it because they already had the F-8 Crusader. It’s a classic case of "right product, wrong time."

- Ballistics Research: For those interested in the physics of the Attridge incident, research "External Ballistics of Aircraft Cannons." It highlights why modern jet fighters have computerized lead-computing optical sights (LCOSS) that account for the aircraft's own velocity to prevent similar incidents.

- Model Building: For hobbyists, the Tiger is a favorite due to its clean lines. Look for the Hasegawa 1:72 scale kits if you want a project that isn't overly complex but shows off that unique mid-century geometry.

The Tiger was a bridge. It bridged the gap between the subsonic dogfighters of Korea and the high-tech, radar-guided missile platforms of the Vietnam era. It wasn't the most successful jet, but man, it was beautiful.