Movies today are loud. They are fast. They are digital. But honestly, if you look at the DNA of every Marvel flick or heist thriller on Netflix right now, you’re looking at a 12-minute silent film from 1903. The Great Train Robbery isn't just an old movie your film history professor makes you watch; it's the moment cinema actually became cinema.

Before Edwin S. Porter sat down to edit this thing, movies were mostly just "living pictures." You’d see a train pull into a station or a guy eating soup. Boring stuff. People liked the novelty, sure, but there wasn't a story. Porter changed that. He realized he could cut between different locations and the audience wouldn't get confused. It sounds simple now. It was revolutionary then.

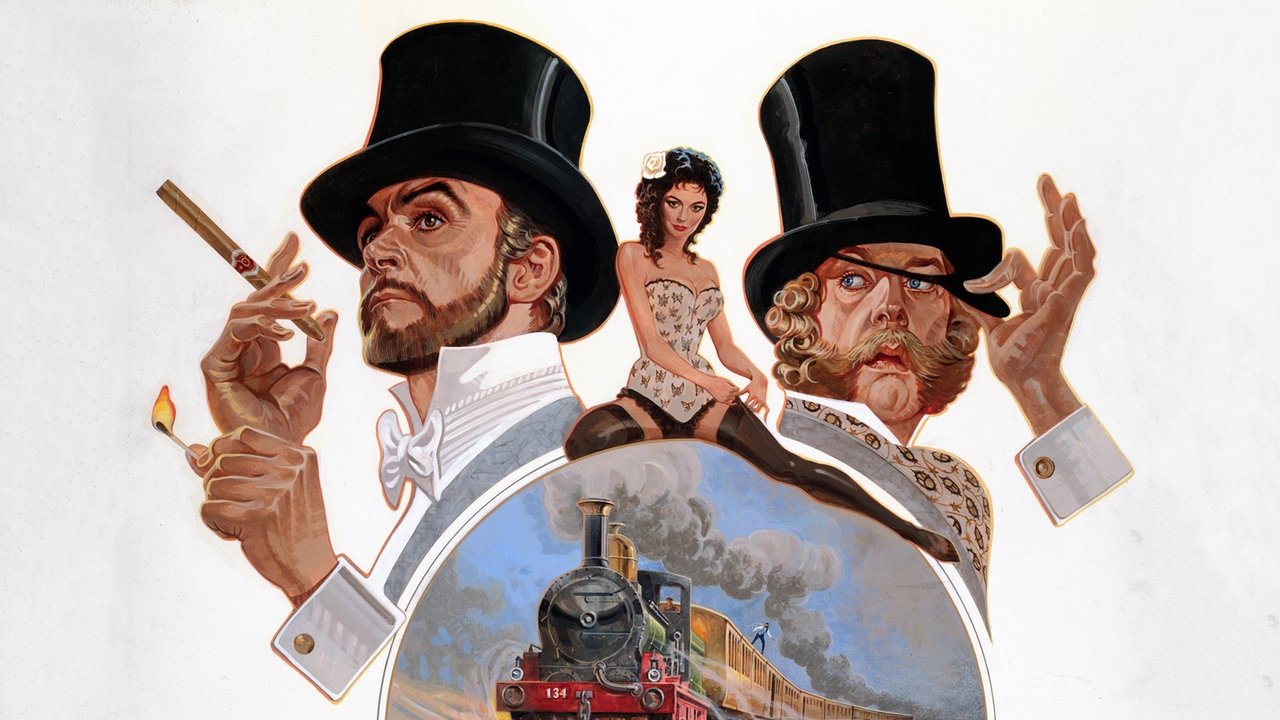

The Myth of the Screaming Audience

You’ve probably heard the legend. It’s the one where audiences in 1903 saw Justus D. Barnes point his pistol at the camera and fire, and everyone screamed and ran out of the theater.

Did it actually happen? Probably not to everyone. But the fact that the story exists tells you everything you need to know about the impact of The Great Train Robbery. For the first time, a movie felt dangerous. It felt real.

The film follows a gang of bandits who tie up a telegraph operator, board a steam locomotive, rob the passengers, and make a getaway. It ends with a shootout. It’s a Western, a heist movie, and an action flick all rolled into one. And it was all done without a single word of dialogue.

Why the Editing Changed Everything

Most people don't realize how stuck in their ways early filmmakers were. They filmed movies like plays. You’d watch a scene from the "front row" of a theater, the scene would end, and that was that.

- Porter threw that out the window.

- He used cross-cutting. This means showing two things happening at the same time in different places.

- While the bandits are escaping, we see the telegraph operator's daughter finding her father and waking him up.

This creates tension. It creates a "meanwhile" in the viewer's head. Without this specific technique, we don't have Inception. We don't have Heat. We don't even have the frantic pacing of a modern TikTok transition. It all starts with Porter’s shears.

👉 See also: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

Realism in 1903: On-Location Shooting

If you watch The Great Train Robbery today, you’ll notice it doesn't look like a cheap stage set. That’s because it wasn’t.

They shot it in New Jersey. Specifically, in the Orange Mountains and along the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad. Using a real train added a level of grit that audiences hadn't seen. When the bandits throw a guy off the moving train—okay, it’s clearly a dummy—it still felt visceral because the environment was authentic.

There's a specific shot where the bandits are running down a hill toward their horses. The camera pans. In 1903, cameras usually stayed dead still. Moving the camera to follow the action was like discovering a new color. It made the world feel bigger than just the frame.

Breaking the Fourth Wall and That Iconic Ending

The most famous shot in The Great Train Robbery actually has nothing to do with the plot. It’s the medium close-up of the outlaw leader, Justus D. Barnes, staring directly into the lens and firing his six-shooter.

Interestingly, the Edison Manufacturing Company’s promotional materials told exhibitors they could put this clip at the beginning or the end of the movie. It didn't matter. It was purely there to shock. It was the first "jump scare" in history, sort of. It broke the "fourth wall" before people even knew what the wall was.

The Controversies and the "Inaccuracies"

History is messy. While we credit Porter with "inventing" the narrative film, he was standing on the shoulders of others. He was heavily influenced by British filmmakers like G.A. Smith and James Williamson. In fact, Williamson’s Stop Thief! (1901) had already experimented with some basic chase sequences.

✨ Don't miss: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

Also, it’s worth noting that the film's depiction of the "Wild West" was already a myth by 1903. The frontier was technically closed. The real "Great Train Robbery" had happened years prior, often involving the Butch Cassidy gang. Porter wasn't documenting history; he was creating the aesthetic of the West that Hollywood would milk for the next century.

Why the Colors Look Weird in Some Versions

If you find a high-quality restoration, you might see splashes of red or yellow. This wasn't "color film" in the modern sense. It was hand-tinted.

Every single frame was painted by hand in a lab. If an explosion went off, someone painted it yellow. If a girl wore a red dress, someone painted that dress on every tiny piece of celluloid. It was an insane amount of labor for a 12-minute short, but it shows how much they wanted to push the medium even then.

How to Watch It Today Without Getting Bored

Don't go into The Great Train Robbery expecting The Godfather. It’s a relic, but a vibrant one.

Look for the "jump cut" when they throw the fireman off the train. It's the first time a filmmaker realized they could stop the camera, swap a human for a dummy, and start it again to create an effect. It’s the birth of special effects.

Watch the background. Since they were filming in public spaces in Jersey, you can sometimes see the smoke from distant factories or the movement of trees. It's a time capsule of the turn of the century.

🔗 Read more: Why Grand Funk’s Bad Time is Secretly the Best Pop Song of the 1970s

The Financial Success That Built an Empire

This wasn't just an artistic success; it was a massive cash cow. It was the most popular film of the pre-nickelodeon era. It toured the country in "traveling shows" where people would pay a few cents to sit in a tent or a rented hall.

The money made from The Great Train Robbery helped solidify the Edison Manufacturing Company as a powerhouse. It also proved to investors that people would pay for stories, not just moving snapshots. This realization is what led to the building of permanent movie theaters. No Porter, no AMC. Basically.

Actionable Insights for Film Buffs and Creators

If you want to truly appreciate the craft or apply these old-school lessons to modern content, keep these points in mind:

Study the "Rule of Three" in the Chase

Notice how the bandits move through three distinct environments: the train, the woods, and the final clearing. This simple structure is still the gold standard for pacing an action sequence.

Experiment with "Dead Space"

Porter allows characters to exit the frame entirely before cutting to the next scene. Modern editing is often too tight. Sometimes, letting a character leave the screen creates a sense of geographic reality that makes your world feel more "lived in."

Check the Library of Congress

The best way to see the film is through the Library of Congress’s digital archives. Avoid the grainy, compressed versions on random YouTube channels. The 4K restorations show details—like the grain of the wood on the telegraph office—that make the experience much more immersive.

Analyze the Violence

Compare the violence in this film to the "Hayes Code" era of the 1930s. Interestingly, The Great Train Robbery is much more brutal. Cinema actually became less realistic and more censored decades after this film was released.

Watching this 1903 masterpiece isn't just a history lesson; it's a way to see the skeleton of modern storytelling. It’s raw, it’s a little clunky, and it’s absolutely essential. Next time you see a movie character look into the camera and wink or fire a gun, you know exactly who did it first.