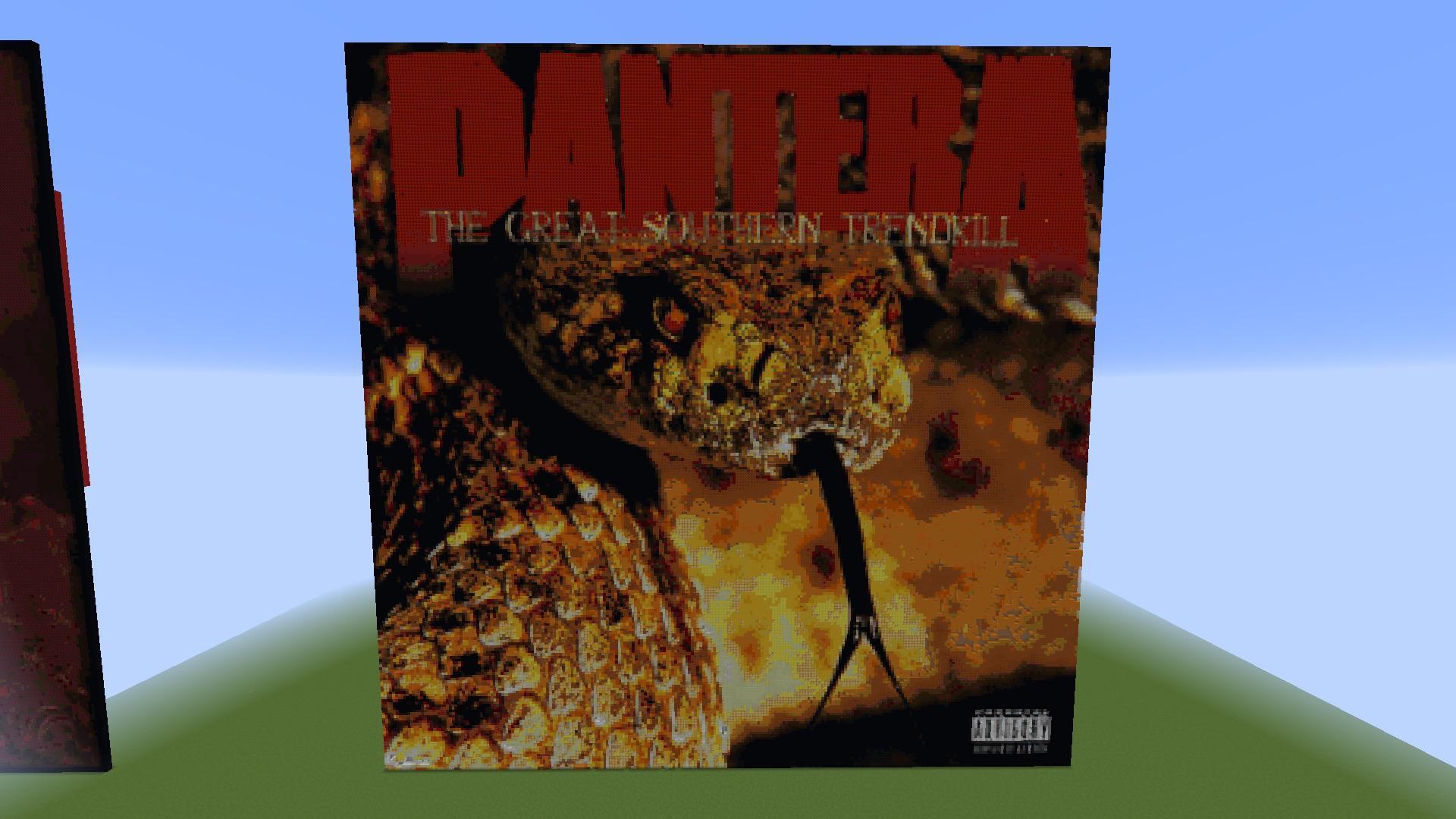

It was 1996. Grunge was dying, but the alternative rock machine was still pumping out "safe" rebellion. Then came The Great Southern Trendkill. It didn't just sound different; it sounded like a nervous breakdown captured on magnetic tape. While their previous effort, Far Beyond Driven, had somehow debuted at number one on the Billboard 200, this record felt like the band was trying to burn the building down with themselves inside.

Pantera was hurting.

If you listen to the opening title track, Phil Anselmo’s scream isn't just a vocal—it’s a literal assault. It’s arguably the most abrasive start to a mainstream metal album in history. There is no "Walk" here. There is no catchy hook to help the medicine go down. It's pure, unadulterated hostility.

Honestly, the context of the recording explains everything. The band was fractured. Vinnie Paul, Dimebag Darrell, and Rex Brown were tracking in Texas at Chasin’ Jason Studios. Meanwhile, Phil was in New Orleans at Trent Reznor's Nothing Studios. They weren't even in the same state. You can feel that isolation in the mix. It’s cold. It’s distant. It feels like a group of men who can't stand to be in the same room but are still tethered together by a shared, burning hatred for the music industry's "trends."

The Raw Nihilism of the Mid-90s Metal Scene

By the mid-90s, the "Trendkill" was literal. Pantera saw the rise of rap-metal and the softening of the scene as a personal insult. They reacted by going deeper into the swamp. The Great Southern Trendkill is often called their "experimental" record, which is a nice way of saying it’s weird as hell.

Take a track like "10's." It’s sludge. It’s slow. It’s got this haunting, melodic undercurrent that feels more like Alice in Chains on a bad trip than the "groove metal" Pantera pioneered. Dimebag’s solo on this track is often cited by guitarists as one of his absolute best—not because it's the fastest, but because the phrasing feels like it's crying.

👉 See also: New Movies in Theatre: What Most People Get Wrong About This Month's Picks

The lyrics were getting darker, too. Phil was struggling heavily with back pain and a burgeoning heroin addiction. You don't have to guess; he tells you. "Suicide Note Pt. I" and "Pt. II" are the centerpiece of the album. Part I is an acoustic, 12-string ballad that sounds genuinely beautiful until you realize what he's singing about. Then Part II hits like a car crash. It’s total noise-core chaos. Most bands wouldn't have the guts to put those two things next to each other. Pantera did.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Production

There’s a common myth that the album sounds "bad" because of the internal tension. That’s a fundamental misunderstanding of what Terry Date and the band were trying to achieve. The production on The Great Southern Trendkill is actually incredibly sophisticated; it’s just designed to make you feel uncomfortable.

The drums have this dry, snapping sound. Vinnie Paul’s kick drums aren't as boomy as they were on Vulgar Display of Power. They’re clicky and precise, like a typewriter made of bone.

- The vocal layering: Phil used a lot of "whisper-screams" and multi-tracking to create a sense of schizophrenia in the audio.

- The guitar tone: Dimebag moved away from the more mid-scooped "standard" metal tone and added a jagged, biting high-end that cuts through the mix like a serrated knife.

- The atmosphere: There are sound effects, static, and ambient noise buried in the tracks that make the whole thing feel claustrophobic.

It’s a record that rewards high-quality headphones. If you just listen to it on cheap speakers, you miss the subtle textures in "Floods." Speaking of "Floods," we have to talk about that outro. It’s widely considered one of the greatest guitar pieces ever written. Dimebag had actually been sitting on that riff since the late 80s. He waited for the right moment to use it, and it fits the apocalyptic vibe of this album perfectly. It sounds like rain falling on a graveyard.

The "Trendkill" Philosophy and the Fallout

The album’s title was a middle finger. Plain and simple.

✨ Don't miss: A Simple Favor Blake Lively: Why Emily Nelson Is Still the Ultimate Screen Mystery

In 1996, the "Southern" identity was becoming a caricature in some parts of media, and Pantera wanted to reclaim the grit of it. They weren't interested in the radio-friendly versions of heavy music that were starting to dominate MTV. Songs like "War Nerve" are essentially manifestos of isolation. "F*** the world for all it’s worth," Phil bellows. It’s not poetic. It’s a blunt force trauma.

Interestingly, the critics at the time didn't really know what to do with it. Rolling Stone gave it a lukewarm review, basically saying it was more of the same but angrier. They missed the point. It wasn't more of the same. It was a deconstruction. It was the sound of a band reaching their commercial peak and deciding they’d rather be feared than loved.

- Commercial Performance: Despite being "unmarketable," it still went Platinum. That’s a testament to the loyalty of their fanbase.

- The Live Era: Touring for this album was notoriously difficult. The tension between Phil and the Abbott brothers was reaching a boiling point.

- Legacy: Today, many die-hard Pantera fans rank this as their favorite specifically because it lacks the "polished" feel of their earlier hits.

Why "Floods" Remains the Centerpiece

If you ask any metalhead about The Great Southern Trendkill, they will eventually bring up "Floods." It’s a seven-minute epic about the world being washed away by a literal and metaphorical deluge.

The song structure is bizarre for a "radio" metal band. It builds slowly, with a clean, chorused guitar line that feels underwater. When the heavy riff finally kicks in, it’s not a fast groove; it’s a slow, punishing grind.

Dimebag’s solo in "Floods" was voted the 15th greatest guitar solo of all time by Guitar World. Think about that. In an era of virtuosos, a solo from a dark, experimental, non-radio-friendly album managed to beat out hundreds of classic rock staples. It’s because it feels human. It’s not just a display of technique—though the "squeals" and whammy bar dives are technically perfect—it’s the emotion. It feels like someone screaming for help underwater.

🔗 Read more: The A Wrinkle in Time Cast: Why This Massive Star Power Didn't Save the Movie

Actionable Insights for the Modern Listener

To truly appreciate what Pantera did here, you have to look past the "tough guy" exterior that often defines the band's image. This is their most vulnerable and honest work.

If you're revisiting the album or hearing it for the first time, keep these things in mind:

- Listen to the bass: Rex Brown is the unsung hero of this record. Because the guitars are so sharp and the vocals are so high, Rex fills in the bottom end with some of the most "liquid" bass lines of his career. He holds the chaos together.

- Watch the "Suicide Note" transition: Listen to "Pt. I" all the way through without skipping. The shock of "Pt. II" hitting is a physical experience you can only get if you sit through the quiet of the first half.

- Check the lyrics: This is Phil Anselmo at his most poetic, despite the screaming. He was dealing with real demons, and the imagery of the "Southern trendkill" as a cleansing fire is a recurring theme that ties the whole messy masterpiece together.

- Compare it to the 20th Anniversary Edition: If you can, find the 2016 anniversary release. It includes early mixes and live takes that show just how much work went into making the album sound as "raw" as it does. It takes a lot of effort to sound this unhinged.

The record stands as a monument to what happens when a band stops caring about "the industry" and starts caring about surviving their own heads. It’s ugly, it’s loud, and it’s arguably the most honest thing 90s metal ever produced.

Next Steps for Deep Diving:

- Listen to "The Underground in America" followed immediately by "Sandblasted Skin." These two closing tracks are essentially one long piece of music that summarizes the band's frustration with the 1996 music scene.

- Read Rex Brown’s autobiography, "Official Truth, 101 Proof." He gives a very blunt account of what the atmosphere was like during these recording sessions and how the separation between New Orleans and Texas nearly ended the band right then and there.

- Analyze the solo in "10's." If you're a musician, look at how Dimebag uses the minor pentatonic scale but bends the notes slightly out of tune to create that "sick" feeling that defines the album's atmosphere.