It didn't start with a bang. It started with a saturated sponge. By the time the flood of 1993 Missouri hit its peak, the ground had been drinking for months. Rain fell in the autumn of 1992, then the snow came, then the spring of '93 brought relentless, pounding storms that just wouldn't quit. Imagine a glass of water filled to the absolute brim. Now, try to add a bucket. That’s basically what happened to the Mississippi and Missouri River basins.

People talk about "100-year floods" or "500-year floods" like they’re scheduled on a calendar. They aren't. Those numbers are just statistical probabilities, a 1% or 0.2% chance of happening in any given year. In 1993, nature blew those stats out of the water. Literally.

The Anatomy of a Slow-Motion Disaster

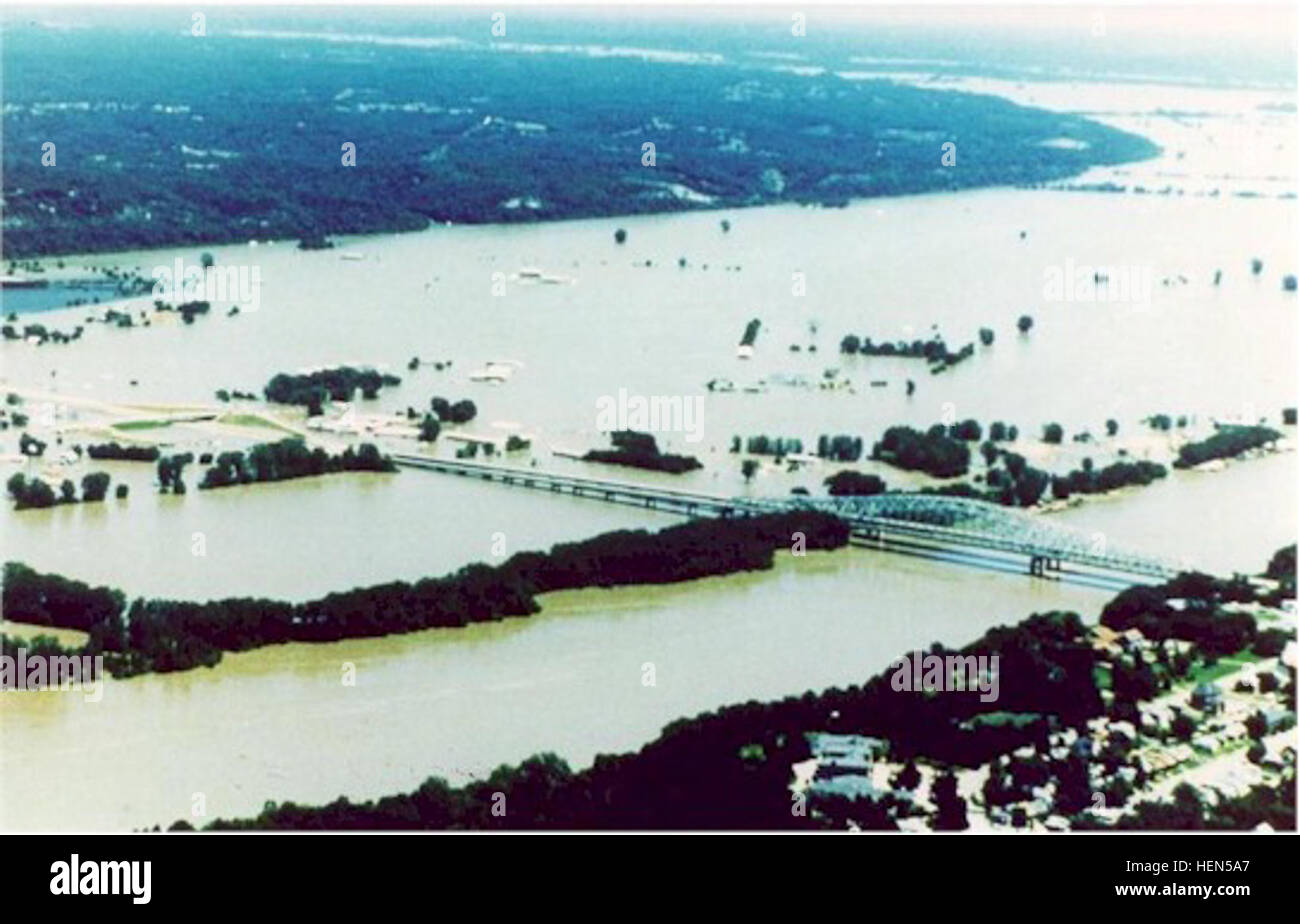

The scale was almost impossible to wrap your head around. We aren't just talking about a few soggy basements. This was a geographical transformation. The Great Flood of 1993 covered about 30,000 square miles. To put that in perspective, you could fit several small New England states into the footprint of the submerged land. Missouri bore the brunt of it because it’s where the "Big Muddy" (the Missouri River) meets the "Father of Waters" (the Mississippi). When both of those giants decide to jump their banks at the same time, there is nowhere for the water to go but into the streets, the cornfields, and the living rooms of thousands of people.

Most floods happen fast. Flash floods rip through a canyon and vanish. Not this one. This was a grinding, months-long siege.

St. Louis saw the Mississippi River stay above flood stage for 80 consecutive days. Think about that for a second. More than two months of watching the water lick the top of the levee, wondering if today is the day the wall gives up. The peak flow at St. Louis reached 1,080,000 cubic feet per second. It’s hard to visualize a million cubic feet of water moving past you every single second, but it’s enough to fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool in the blink of an eye.

💡 You might also like: Quién ganó para presidente en USA: Lo que realmente pasó y lo que viene ahora

When the Levees Broke: The Monarch Levee and Beyond

There’s a common misconception that the levees just "failed" because they were weak. Honestly, it's more complex. Many levees were overtopped, meaning the water simply went over the top because it was higher than anyone ever anticipated. Others failed due to "piping," where the pressure of the river forces water through the soil underneath the levee, eventually causing the whole structure to collapse inward.

Take the Monarch Levee in Chesterfield, Missouri. It was supposed to protect a massive 4,700-acre valley full of businesses and an airport. On July 30, 1993, it snapped. The "Spirit of St. Louis" Airport became a lake. Millions of dollars in business assets were swallowed in hours.

It wasn't just big cities. Small towns like Rhineland, Missouri, faced a choice: rebuild and wait for the next one, or move the entire town to higher ground. They chose to move. They literally picked up houses and relocated them to the bluffs. If you visit Rhineland today, you’re looking at a town that retreated in the face of a superior enemy.

The Human Cost Nobody Forgets

Statistics like $15 billion in damages (in 1993 dollars) or 50 deaths are easy to read in a textbook. They don't tell the story of the sandbag lines. You had grandmothers standing next to National Guard troops for 20 hours a day, passing heavy bags of grit until their hands bled. There was a weird, desperate camaraderie in it. People were fighting for their towns, their history.

📖 Related: Patrick Welsh Tim Kingsbury Today 2025: The Truth Behind the Identity Theft That Fooled a Town

Then there’s the story of the Quincy, Illinois bridge. It was the only crossing open for over 200 miles. People were driving hours out of their way just to get across the river. And then, James Scott intentionally sabotaged a levee at West Quincy to strand his wife on the other side so he could keep partying. He was later convicted of causing a catastrophe. It sounds like a bad movie plot, but it’s a real, dark part of the flood of 1993 Missouri lore.

Lessons Learned (and Some We Ignored)

After the water receded in the fall, the federal government realized that just rebuilding wasn't enough. The "Galloway Report" came out in 1994, led by Brigadier General Gerald Galloway. It was a massive wake-up call. It basically said we need to stop trying to choke the river into a narrow straw and give it some room to breathe.

- Buyouts: The government spent millions buying out thousands of homes in the floodplain. If the house is gone, the river can’t destroy it next time.

- Wetland Restoration: We started to realize that wetlands act like natural sponges. Paving them over for strip malls was a bad move.

- Levee Policy: There was a push for stricter standards, but this is where it gets messy.

There is still a massive debate about "levee wars." If one town builds a higher levee, it just pushes the water over to the neighbor across the river who can’t afford a bigger wall. It’s a classic "beggar thy neighbor" scenario that still causes tension in Missouri today. You see new developments popping up in the Chesterfield Valley now, protected by even bigger levees. Some experts, like Nicholas Pinter, a geology professor who has studied the Mississippi for decades, argue that we are just setting ourselves up for a more expensive disaster later.

Is Missouri Ready for the Next One?

Since 1993, we’ve had "great" floods again in 2008, 2011, and 2019. The 2019 event actually lasted longer in some places than '93 did. We have better satellite imaging now. Our computer models can predict crests with much more accuracy. But the climate is changing, and the "100-year" events are happening every decade.

👉 See also: Pasco County FL Sinkhole Map: What Most People Get Wrong

The flood of 1993 Missouri remains the benchmark because of its sheer persistence. It redefined how the Army Corps of Engineers looks at the river. It changed the physical map of the state. Most importantly, it changed the psychology of the people living along the banks. You don't "beat" the Missouri River. You just negotiate with it.

Actionable Insights for Living with the River

If you live in Missouri or any major river basin, "1993" isn't just a date; it's a warning. Here is how that history should inform your current decisions:

- Check the "Base Flood Elevation" (BFE): Don't just trust a "not in a flood zone" label from a realtor. Check the actual elevation of your lowest floor versus the BFE. If you’re even close, get flood insurance. Standard homeowner’s insurance covers almost nothing related to rising river water.

- Understand Levee Protection Limits: A levee is only as good as its weakest point. If you live behind one, know who maintains it. Is it a private levee district or the Army Corps? Private districts often lack the funds for major repairs.

- Landscape for Drainage: If you're on a slope near the Missouri or Mississippi tributaries, use rain gardens and native deep-rooted plants. They won't stop a 50-foot crest, but they stop the localized "flash" saturation that ruins foundations.

- Digital Backup: In 1993, people lost every photo they owned. Today, there's no excuse. Keep your "vital records" and family history in the cloud. If you have to evacuate, you should only be carrying people and pets.

- Support Floodplain Preservation: Support local initiatives that turn flood-prone land into parks or conservation areas. A park can go underwater and be fine a week later. A subdivision cannot.

The 1993 flood was a generational trauma, but it was also a masterclass in hydrology. The river is going to take what it wants eventually; our job is just to stay out of its way when it does.