If you’ve ever looked at a graph of national debt over time, you probably felt a pit in your stomach. It’s a line that doesn't just go up; it practically teleports toward the ceiling. Honestly, it looks less like a fiscal record and more like a mountain climber trying to reach the stratosphere without a rope.

Money is weird. Especially when we talk about trillions. Most of us can barely wrap our heads around a million dollars, let alone the $34 trillion plus that the U.S. currently owes. But that single line on the chart tells a story about wars, pandemics, tax cuts, and how we decided to pay for—or not pay for—the world we live in.

The Shape of the Curve

Early on, the graph of national debt over time was basically flat. For decades after the founding of the United States, the line barely budged. Debt was something you took on for a specific reason, like the Revolutionary War or the War of 1812, and then you paid it off. Andrew Jackson actually managed to bring the debt to zero in 1835. It didn't last long.

The Civil War changed everything. You can see the first real "spike" there. It’s a sharp, jagged needle on the graph. When the North and South stopped fighting, the debt started to drift back down, but it never hit zero again. This established a pattern. We spend big when things get desperate, and then we try—usually unsuccessfully—to level things out later.

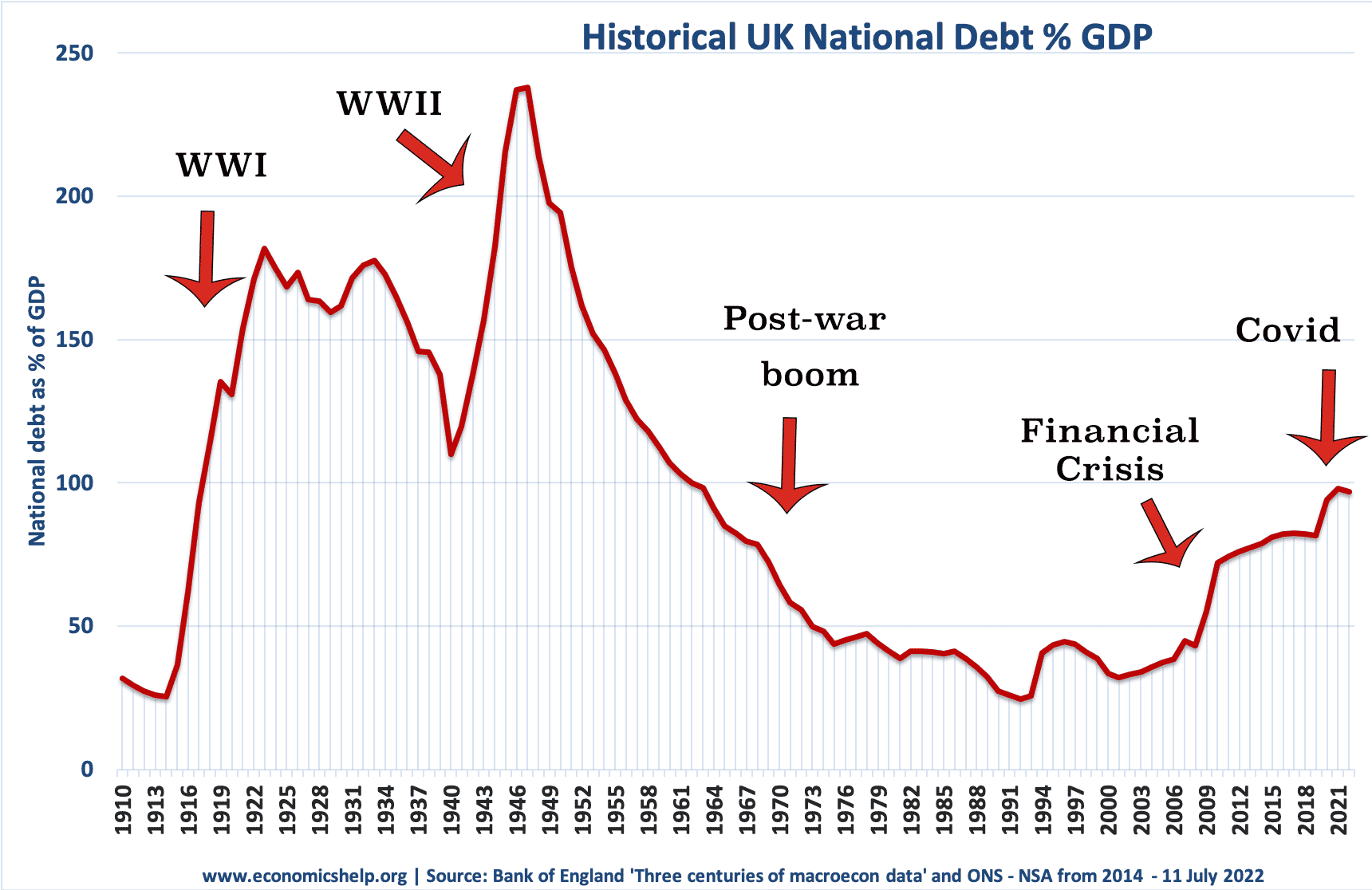

World War I and World War II created massive vertical leaps. World War II is the big one. Debt as a percentage of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) hit roughly 106% back then. That’s a key metric. It’s not just about the raw number; it’s about how much we owe compared to how much our economy actually produces. If you make $50,000 a year and owe $5,000, you’re fine. If you make $50,000 and owe $500,000, you have a problem.

The Great Decoupling of the 1980s

For a long time, the debt-to-GDP ratio actually went down after WWII. The economy was booming. We were building highways and suburbs. Even though the "total debt" number was rising slowly, the economy was growing faster.

Then came the 80s.

Under the Reagan administration, we saw a shift in philosophy. Tax cuts were deep, and defense spending went through the roof. The graph of national debt over time stopped being a series of bumps and started looking like a ramp. We started running "structural deficits." This means we were spending more than we took in even when there wasn't a world-ending crisis happening.

👉 See also: Sands Casino Long Island: What Actually Happens Next at the Old Coliseum Site

It’s kinda like using a credit card to buy groceries every single month because your paycheck doesn't cover the rent. You might survive for a while, but the interest starts to eat you alive.

By the time we hit the 1990s, people were panicked. You might remember Ross Perot and his famous charts. He stood on national television with a literal pointer, showing everyone how the debt was spiraling. For a brief moment under Bill Clinton, the budget actually saw a surplus. The line on the graph slowed down. Some people even worried about what would happen if we paid the debt off entirely. They needn't have bothered.

The 21st Century Explosion

The 2000s were a disaster for the balance sheet. First, the dot-com bubble burst. Then came 9/11 and the subsequent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Tax cuts in 2001 and 2003 further drained the coffers.

Then the 2008 financial crisis hit.

This is where the graph of national debt over time turns into a vertical wall. When the housing market collapsed, the government stepped in with massive stimulus packages. Tax revenue plummeted because people weren't working. The debt jumped by trillions in just a few years.

But wait, there’s more.

The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 makes the 2008 spike look small. The government pumped trillions into the economy to keep businesses afloat and people fed. It worked in the sense that we avoided a total depression, but the price tag was staggering. We are now in a territory where the debt is significantly larger than our entire annual GDP.

✨ Don't miss: Is The Housing Market About To Crash? What Most People Get Wrong

Why This Matters to Your Wallet

You might be thinking, "Who cares? It's all just numbers on a screen." I get it. But the graph of national debt over time has real-world consequences that show up in your life every day.

- Inflation: When the government prints or borrows massive amounts of money, it can devalue the currency. If there are more dollars chasing the same amount of goods, prices go up. Look at your grocery bill lately? Yeah.

- Interest Rates: The U.S. has to pay interest on all that debt. As interest rates rise, the cost of servicing that debt explodes. Right now, we spend more on interest payments than we do on some major government departments.

- Crowding Out: When the government borrows trillions, it competes with private businesses for loans. This can drive up interest rates for your mortgage, your car loan, and your credit cards.

The Role of Social Security and Medicare

We often blame "pork barrel" spending or foreign aid for the debt. Honestly? That's small potatoes. The real drivers on the graph of national debt over time are mandatory spending programs: Social Security and Medicare.

As the Baby Boomer generation retires, these costs are skyrocketing. We have fewer workers paying into the system and more retirees drawing out of it. It’s a math problem that nobody in Washington wants to touch because "fixing" it usually involves raising taxes or cutting benefits—both of which are political suicide.

According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), if we don't change course, the interest on our debt will eventually become the largest single item in the federal budget. Think about that. We’d be spending more on interest to bankers and foreign governments than we do on our own military or our own children's education.

Is There a "Cliff"?

Economists are split on this. Some, who subscribe to Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), argue that as long as a country prints its own currency, it can’t really "go bankrupt." They suggest the only real limit is inflation.

Others, like the folks at the Peter G. Peterson Foundation, warn that we are heading for a fiscal crisis. They argue that at some point, investors will lose confidence in the U.S. dollar. If people stop wanting to buy our debt, the whole house of cards falls down.

The truth is probably somewhere in the middle. We aren't going to wake up tomorrow and find the U.S. "closed for business." But we are slowly losing our flexibility. Every dollar spent on interest is a dollar that isn't spent on fixing bridges, curing diseases, or lowering your taxes.

🔗 Read more: Neiman Marcus in Manhattan New York: What Really Happened to the Hudson Yards Giant

What You Can Actually Do

You can't fix the national debt by yourself. Sorry. But you can protect yourself from the volatility that a spiraling graph of national debt over time creates.

First, understand that inflation is likely here to stay in some capacity. Holding all your wealth in cash is risky when the dollar is being devalued. Real assets—things like real estate, stocks in companies with "pricing power," or even gold—tend to hold their value better when the debt goes wild.

Second, pay attention to the "debt ceiling" debates. They happen almost every year now. Most of the time, it's just political theater, but if the U.S. ever actually defaulted on its debt, the global financial system would basically explode. It’s worth keeping an eye on.

Third, look at your own debt. If the government is struggling with interest rates, you will too. If you have high-interest debt, pay it off now. When the national debt is high, the economy is more fragile. You want to be as lean as possible.

Actionable Steps for the Future

To navigate the reality shown in the graph of national debt over time, you need a strategy that assumes the line will keep going up.

- Diversify your income. Don't rely on a single source of revenue, especially one tied to government funding or sectors sensitive to interest rates.

- Audit your portfolio. Ensure you have "inflation-resistant" assets. This might include TIPS (Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities) or diversified index funds.

- Stay informed but skeptical. Politicians will use the debt graph to scare you into voting for them. Look at the actual CBO reports. The data is public. The numbers don't lie, but the people talking about them often do.

- Hedge against currency risk. Consider having some exposure to international markets or assets not denominated in USD.

The graph is a warning. It shows a country that has lived beyond its means for decades. While the "day of reckoning" hasn't arrived yet, the margin for error is getting thinner every year.

Understand the trend. Protect your assets. Don't wait for a "balanced budget" that might never come.

Next Steps for Your Finances:

Begin by reviewing your long-term investment strategy. Check if your retirement accounts are weighted too heavily in fixed-income assets that might lose purchasing power if inflation spikes due to debt monetization. Consult a fee-only financial advisor to discuss how a potential sovereign debt crisis or prolonged high-interest environment would impact your specific net worth.

Check the current U.S. Debt Clock online to see the real-time movement of these figures. Comparing the "Debt per Taxpayer" to your own household income provides a sobering perspective on the scale of the challenge. Finally, contact your local representatives to ask for their specific, math-based plan for addressing the long-term solvency of Social Security, as this remains the single largest driver of future debt projections.