John Ford was a man of contradictions. He was a grumpy, eye-patch-wearing conservative who loved the military, yet he directed what is arguably the most radical, pro-labor film ever to come out of a major American studio. Honestly, it’s a miracle The Grapes of Wrath movie even got made in 1940. Think about the timing. The Great Depression was still a raw, bleeding wound for millions of people. The "Okies" were still living in ditches. When Darryl F. Zanuck, the head of 20th Century Fox, bought the rights to John Steinbeck’s novel, people thought he’d lost his mind. It was a "communist" book. It was banned. It was burned.

Yet, somehow, it became a masterpiece.

If you watch it today, the first thing that hits you isn't the politics. It’s the shadows. Gregg Toland, the cinematographer who would later go on to film Citizen Kane, shot this movie like a horror film. Faces are half-hidden in darkness. The dust looks like it's choking the life out of the frame. It doesn’t feel like a dusty old relic from the TCM vault; it feels like a dispatch from a war zone. And in a way, it was.

The Secret Production of The Grapes of Wrath Movie

Zanuck was terrified of sabotage. The Associated Farmers of California, a powerful group of corporate landowners, hated the book with a burning passion. They saw it as a direct attack on their business model, which—let’s be real—was basically indentured servitude. To keep them off the scent, the production was shrouded in secrecy. They used the working title Highway 66.

They didn't want any protests or legal injunctions stopping the cameras from rolling.

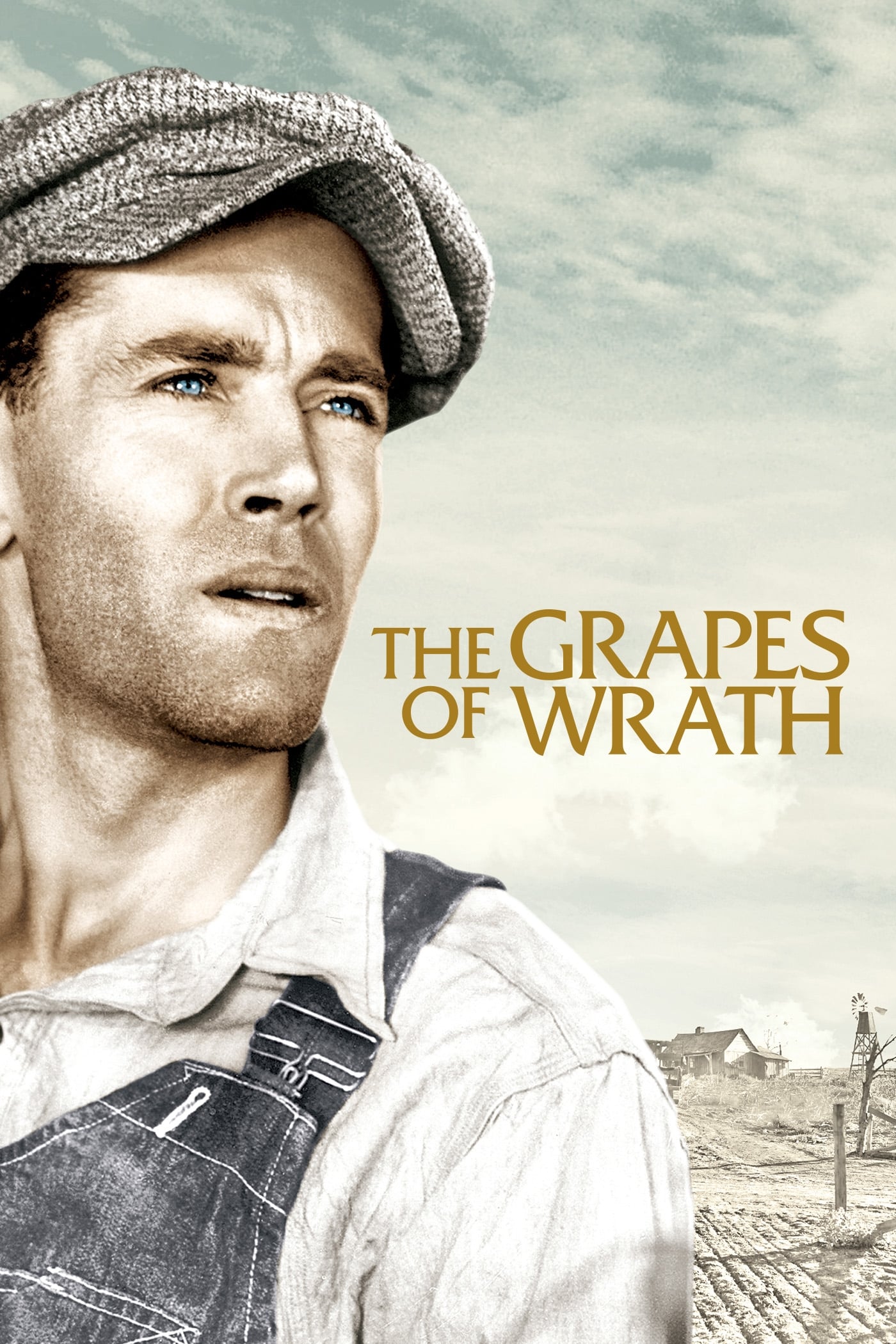

Henry Fonda wasn't even the first choice for Tom Joad. Zanuck actually wanted Tyrone Power, the studio's big heartthrob at the time. Can you imagine? Power was a great actor, but he had that "movie star" glow. Fonda, on the other hand, had these hollow cheeks and eyes that looked like they hadn't seen a full meal in three years. He ended up signing a long-term contract with Fox just to get the role. It was a deal with the devil that he hated for years, but it gave us one of the greatest performances in cinema history.

The film follows the Joad family as they are kicked off their land in Oklahoma. The "cats," as they call the tractors, literally bulldoze their homes. They pile everything they own onto a rickety truck and head to California, the promised land. But California isn't a paradise. It’s a police state where "Okie" is a slur and hunger is used as a weapon to keep wages low.

👉 See also: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

Realism vs. The Hays Code

One of the biggest hurdles for The Grapes of Wrath movie was the Motion Picture Production Code, better known as the Hays Code. This was the era of strict censorship. You couldn't have "foul" language. You couldn't be too bleak. You definitely couldn't show the ending of the book—where Rose of Sharon, after losing her baby, breastfeeds a starving man to save his life.

That was never going to happen in 1940.

Instead, Ford and screenwriter Nunnally Johnson had to pivot. They shifted the focus from the sheer, crushing biological misery of the book to a more spiritual, communal kind of hope. It’s a different beast than Steinbeck’s novel. Some purists hate that. They think it "Hollywood-ized" the struggle. But if you look at the scene where the Joads arrive at the government-run Wheatpatch camp, you see what Ford was doing. He was showing that dignity is possible when people actually give a damn about each other. It was a pro-New Deal message that resonated deeply with an audience that was still standing in bread lines.

Why the Cinematography Changes Everything

Most movies from the early 40s look... well, like they were shot on a stage. They have that flat, bright "studio" lighting. Gregg Toland hated that. He wanted the The Grapes of Wrath movie to feel visceral. He used "source lighting," meaning if there was a candle on a table, that was the only light hitting the actor's face.

It was revolutionary.

When Tom Joad comes home from prison at the start of the movie, the house is empty. It’s a skeleton. The way Toland uses a single lantern to track Muley Graves (played by a frantic John Qualen) as he describes the "cats" coming across the land is pure cinema. It turns a historical event into a mythic nightmare. You feel the dust in your throat.

✨ Don't miss: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

The Famous "I'll Be There" Speech

We have to talk about the ending. Specifically, Tom Joad’s farewell to Ma.

"I’ll be all around in the dark. I’ll be everywhere. Wherever you look. Wherever there’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there."

It’s iconic. It’s been quoted by everyone from Bruce Springsteen to political activists. But here’s the thing: Henry Fonda delivered that speech in basically one take, with almost no light. He’s whispered it. He didn't shout it like a politician. He said it like a man who had finally realized he was part of something bigger than himself. It’s the moment the character transcends his own skin.

Jane Darwell, who played Ma Joad, won an Oscar for her performance. She was the anchor. While the men were breaking or getting angry, she was the one who kept the family "clear and whole." Her final line—"We’re the people that live. They can’t wipe us out. They can’t lick us. We’ll go on forever, Pa, ‘cause we’re the people"—is the heartbeat of the film.

The Backlash and the Legacy

Even after the movie was a hit, the controversy didn't stop. The FBI kept a file on the production. People called it propaganda. In some towns, theaters were pressured not to show it. It’s wild to think about now, but a movie about a family looking for work was considered a threat to the American way of life by some of the most powerful people in the country.

What people often forget is that the movie actually ends on a more hopeful note than the book. Steinbeck’s novel is a downward spiral into a dark pit. The movie suggests that through collective action and government assistance, there's a way out. This was very much in line with the politics of the time, specifically Franklin D. Roosevelt's administration.

🔗 Read more: Alfonso Cuarón: Why the Harry Potter 3 Director Changed the Wizarding World Forever

Is it still relevant?

You've probably seen the headlines lately. Mass migrations. Economic inequality. Housing crises. The themes of The Grapes of Wrath movie haven't aged a day. When you see the Joads being turned away at the border of California by armed guards, it looks like something you’d see on the news tonight.

That’s why it’s not just a "classic." It’s a mirror.

Interestingly, John Ford himself claimed he wasn't interested in the politics. He said he just liked the story of the "underdog." Typical Ford. He always tried to hide his brilliance behind a mask of "just doing a job." But you don't direct a movie with this much soul by accident. He captured the American spirit in its most battered, bruised, and resilient state.

Surprising Facts You Might Not Know

- The Truck: The Hudson Super Six truck used in the film was actually weighted down to make it look like it was struggling under the load. It became a character in its own right.

- The Cast: Many of the "extras" in the camp scenes were actual migrant workers. Ford wanted that authenticity. You can see it in their faces—those aren't actors with makeup; those are people who have lived that life.

- The Music: The use of "Red Wing" and "Going Down the Road Feeling Bad" gives the film a folk-documentary feel. It doesn't use a sweeping, over-the-top orchestral score for most of the emotional beats. It stays grounded.

- The Director's Cut: There wasn't one. In those days, the studio and the director usually worked in tandem, but Zanuck actually edited the final sequence (the "We're the people" speech) because he wanted a more uplifting ending than what Ford originally shot.

How to Experience The Grapes of Wrath Today

If you’re going to watch it, don't watch a compressed, low-quality stream on a phone. This is a movie that demands a big screen (or at least a good TV) because of Toland’s cinematography. The contrast between the deep blacks and the harsh whites is the whole point of the visual language.

What to look for on your first watch:

- The Hands: Notice how often Ford focuses on the characters' hands. Working hands. Dirty hands. Hands holding onto each other. It’s a recurring motif of human connection.

- The Silence: Unlike modern movies that feel the need to fill every second with noise, this film isn't afraid of quiet. The silence in the abandoned Joad farmhouse is deafening.

- The Transformation of Tom: Watch how Henry Fonda goes from a selfish, guarded ex-con to a revolutionary. It’s a slow burn.

The Grapes of Wrath movie remains a towering achievement because it refuses to look away. It’s uncomfortable. It’s sad. But it’s also incredibly beautiful. It reminds us that even when the system fails, the people—the "plain folks"—usually find a way to keep walking.

Actionable Next Steps

If the themes of the film sparked an interest, here’s how to dive deeper into the history and the craft:

- Compare the Ending: Read the final chapter of Steinbeck's novel. It is radically different and much more controversial than the film's conclusion. Understanding why Hollywood changed it tells you a lot about 1940s culture.

- Study Gregg Toland: Check out Citizen Kane or The Little Foxes. You’ll start to see the "Toland style" (deep focus and high-contrast lighting) that changed how movies were made forever.

- Research the "Dust Bowl": Look into the actual history of the Resettlement Administration and the Farm Security Administration (FSA). The famous "Migrant Mother" photograph by Dorothea Lange was a huge visual influence on John Ford.

- Watch 'Beyond the Epic': Seek out documentaries on John Ford's career to understand how a conservative director became the voice of the displaced American worker.