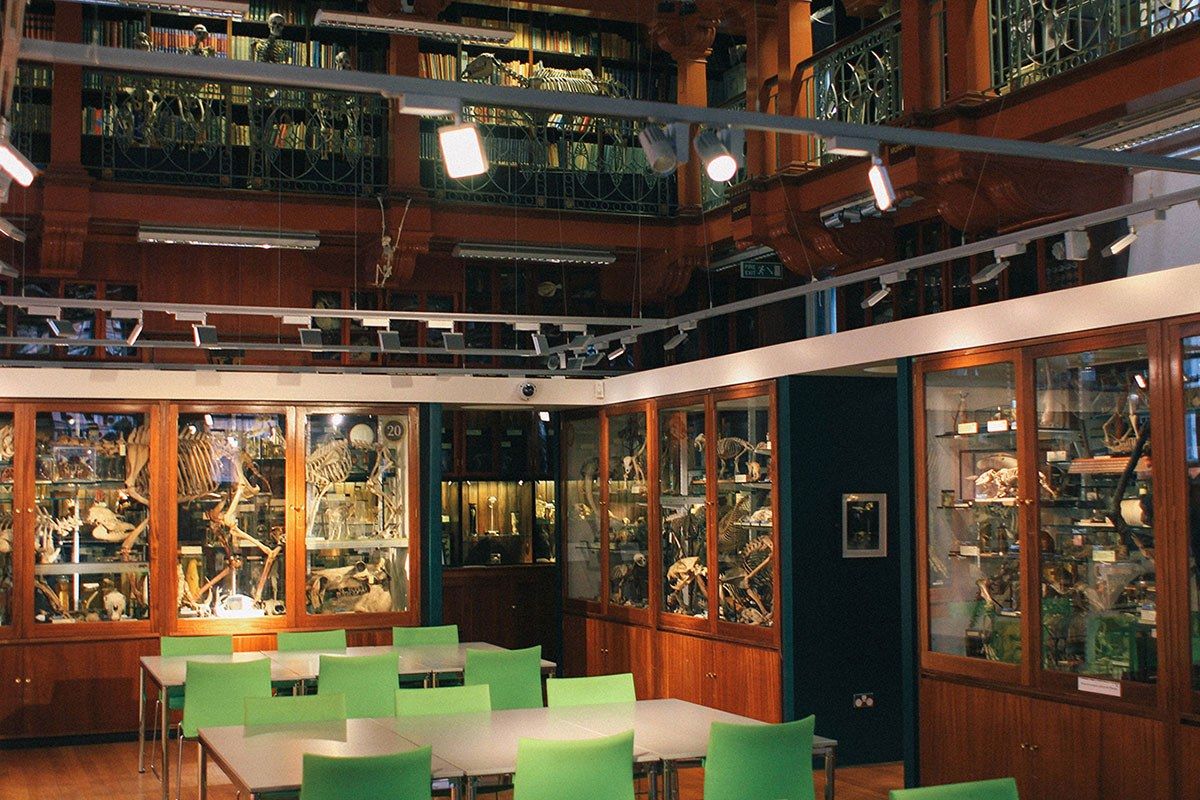

You’re walking down a quiet street in Bloomsbury, dodging students from University College London, and you stumble into a room that smells faintly of old books and very old spirit jars. It’s not a big space. Honestly, it’s tiny compared to the hulking mass of the Natural History Museum over in South Kensington. But the Grant Museum of Zoology London is different. It’s dense. It feels like someone took the attic of a Victorian mad scientist and packed it into a single, high-ceilinged hall.

There are no animatronic dinosaurs here. No gift shop selling plastic trilobites. Instead, you get a jar of moles. A literal jar. Packed with about eighteen of them, noses pressed against the glass like they’re trying to see out. It’s bizarre. It’s arguably the most famous thing in the building. People come from all over the world just to look at the "Jar of Moles." Why? Because it’s tactile, weird, and perfectly summarizes what this place is: a teaching collection that survived the era of digital models and somehow became more relevant because of it.

The chaos of a 19th-century classroom

Robert Edmond Grant started this whole thing in 1828. He was the first Professor of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy in England. Think about that for a second. Before he showed up, people weren't really "studying" animals this way in a formal university setting. Grant was a radical. He was an evolutionist before Darwin even published On the Origin of Species. In fact, he was one of Darwin's mentors in Edinburgh.

The collection wasn't meant for tourists. It was a library of bodies. If you were a medical student or a budding biologist in the 1830s, you couldn't just Google "what does a dugong heart look like?" You had to see it. You had to touch it. Grant spent his life gathering 68,000 specimens so his students had something to look at.

Walking through the Grant Museum of Zoology London today feels like stepping into his brain. The shelves go all the way to the ceiling. Glass cases are crammed with skeletons, wet specimens in alcohol, and taxidermy that looks a bit... well, let's say "vintage." Some of the taxidermy was done by people who had never actually seen the living animal. It shows.

The Quagga: A ghost in the room

Let’s talk about the Quagga. This is one of the rarest skeletons on Earth. The Quagga was a subspecies of zebra that had stripes only on the front half of its body. They lived in South Africa. By the late 1880s, they were gone. Extinct.

📖 Related: Why San Luis Valley Colorado is the Weirdest, Most Beautiful Place You’ve Never Been

The Grant Museum has one of only seven Quagga skeletons known to exist. It’s not just a bone pile; it’s a physical reminder of how fast we can erase a species. When you stand next to it, you realize how fragile the whole thing is. The skeleton was actually misidentified for years. It was just "the zebra" until someone took a closer look and realized what they actually had. That’s a recurring theme here. You’re often looking at something world-class without even knowing it because the labels are understated.

The Micrarium: Tiny things in big light

There’s this corner of the museum that looks like a glowing blue cave. They call it the Micrarium. It’s basically a converted storage closet lined with backlit microscope slides.

Most museums ignore the small stuff. They want the whales. They want the tigers. But the vast majority of the animal kingdom is smaller than a fingernail. In the Micrarium, you’re surrounded by thousands of tiny slices of life—squid embryos, flea legs, microscopic parasites. It’s beautiful in a way that’s hard to describe. It’s art made from science.

Why the jars aren't just gross

Some people get a bit squeamish in the "wet collection" section. There are jars of brains. Jars of lizard tongues. Jars of... things you can't quite identify at first glance. But look closer.

Look at the bisected heads. You can see the internal plumbing of a horse or a dog. It’s not meant to be macabre; it’s meant to show the engineering of life. You start to see the similarities. The way a flipper has the same bone structure as your hand. Grant was obsessed with these connections. He wanted people to see the "unity of plan" across different species.

👉 See also: Why Palacio da Anunciada is Lisbon's Most Underrated Luxury Escape

What most people get wrong about the Grant Museum

People often assume it’s a "dead" museum. They think it’s just a static relic of the Victorian era. It isn't.

UCL researchers still use these specimens. They do DNA sequencing on the old samples. They use the skeletons to study how bones change over time due to environmental factors. It’s a working lab that happens to let the public in for free.

Also, don't expect a quiet, reverent atmosphere. Because it's a university museum, it’s often full of students sketching or researchers debating. It’s loud. It’s lived-in. It’s the opposite of the polished, sterile experience you get at the big museums in South Kensington.

The "Underwhelming" Fossil Fish

One of my favorite things is the "Underwhelming Fossil Fish of the Month" blog and display. It’s a self-aware joke the curators run. They realize that not every fossil is a T-Rex. Some fossils are just gray, lumpy rocks that used to be a fish’s fin. By highlighting the boring stuff, they actually make the science more accessible. They’re basically saying, "Hey, science is often just looking at gray rocks and trying to figure out why they matter." It’s honest. I like that.

How to actually visit without missing the good stuff

If you’re planning to go, you need to know a few things. First, it’s free. Completely. But they have weird hours because, again, it’s a university space. Usually, it’s open in the afternoons, Tuesday through Saturday. Always check the UCL website before you trek down there.

✨ Don't miss: Super 8 Fort Myers Florida: What to Honestly Expect Before You Book

- Look Up: Some of the coolest skeletons are hanging from the ceiling or tucked on top of the cabinets.

- The Glass Cases: Don't just look at the big stuff. Peer into the corners of the cases. You’ll find things like the "Neglected" collection—specimens that were lost in drawers for decades.

- The Brains: There’s a shelf of brains. It’s fascinating to compare the size of a shark brain to a rabbit brain.

The ethical elephant in the room

We have to talk about how these things got here. In the 19th century, collecting was often colonial and exploitative. The Grant Museum doesn't shy away from this. They are actively working on "decolonizing" the collection. This means being transparent about where the animals came from and the history of the people who collected them. They have displays that talk about the problematic history of natural history. It’s a nuanced approach that acknowledges that while the specimens are scientifically valuable, the way they were acquired wasn't always ethical.

Practical Insights for Your Visit

Don't rush it. You can walk across the room in thirty seconds, but you could spend three hours looking at a single shelf.

If you have kids, they’ll either love it or be slightly traumatized by the jar of moles. Most love it. It’s like a real-life version of an I-Spy book.

Combine your visit with the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, which is just around the corner on the same campus. It’s equally cramped and packed with incredible things. Between the two, you’ll get a dose of history and science that feels much more personal than the "big" London attractions.

Actionable Next Steps

- Check the opening times: The museum is currently located in the Rockefeller Building on University Street. Hours can fluctuate during university holidays.

- Follow the "Mole Cam": Yes, the jar of moles has its own social media presence sometimes. It’s a great way to see what events are happening.

- Bring a sketchbook: Even if you aren't an artist, drawing the specimens forces you to see details you’d otherwise miss.

- Volunteer: If you’re a local or a student, they often have programs for "Engagers" who stand in the museum and talk to visitors about the specimens.

- Donate: Since it’s a free museum, they rely on grants and donations to keep the spirit jars topped up and the bones dusted. Every little bit helps keep this weird slice of London alive.

You won't find a café inside. You won't find a 4D cinema experience. You’ll just find a lot of glass, a lot of bone, and a deep, slightly dusty appreciation for the sheer variety of life on this planet. It’s the Grant Museum of Zoology London. It’s weird. Go see it.