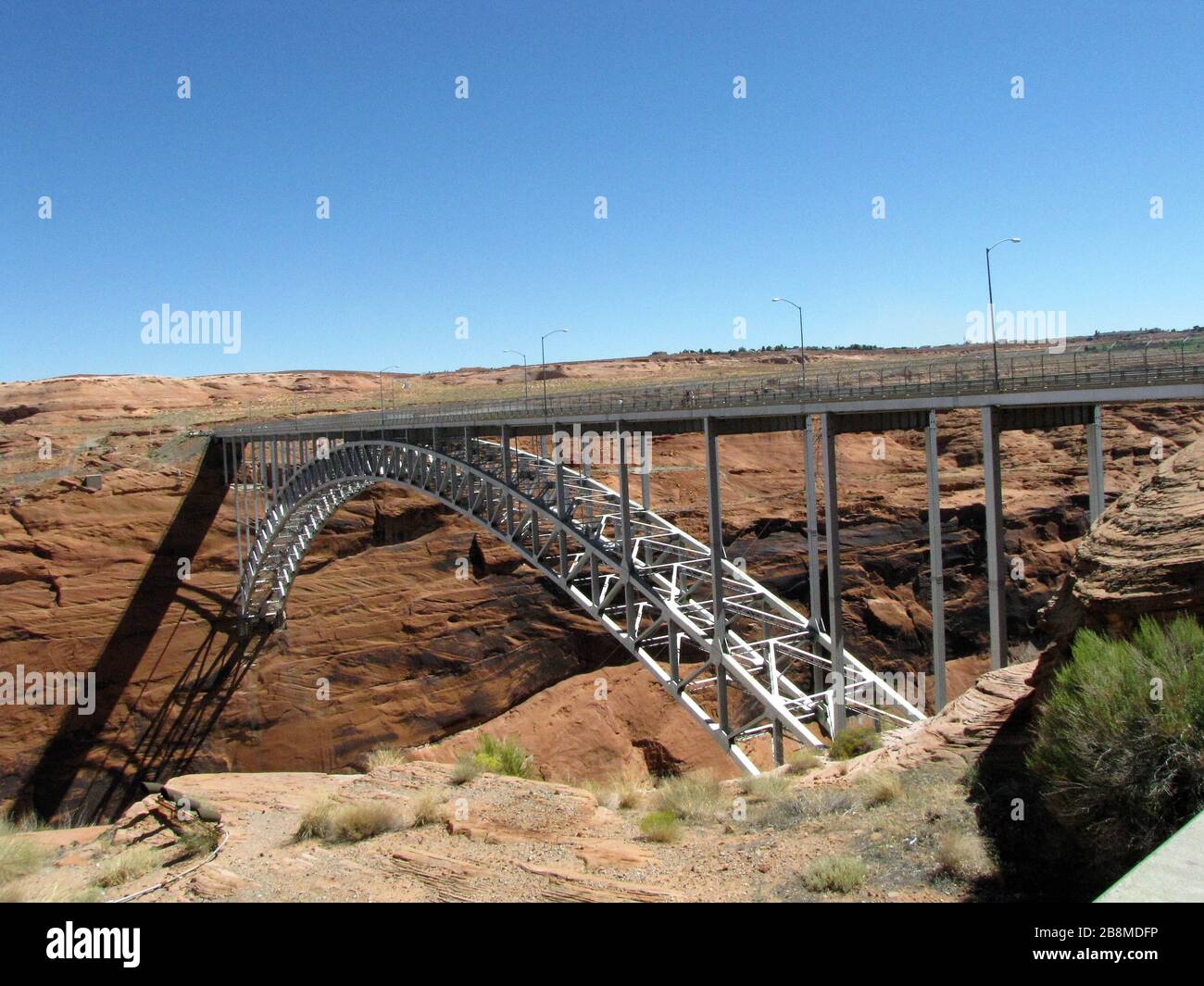

It is a massive, curved wall of concrete wedged into the red rock of Northern Arizona. If you’ve ever stood on the bridge right next to it, the scale of the Glen Canyon Dam—or barrage de Glen Canyon if you're looking at it through a French lens—is honestly dizzying. It’s over 700 feet tall. It holds back Lake Powell, the second-largest man-made reservoir in the United States. But lately, the conversation around this behemoth has shifted from wonder to genuine worry.

The water is disappearing.

For decades, we treated the Colorado River like an infinite checking account. We built cities like Phoenix and Las Vegas on the back of this infrastructure. But the drought isn't just a "dry spell" anymore; it’s a fundamental shift in the climate of the American West. When the water level in Lake Powell drops, it isn't just bad for boaters at Antelope Canyon. It’s a threat to the power grid and the very stability of the dam's internal plumbing.

The Plumbing Problem Nobody Saw Coming

People talk about "dead pool" like it's a movie title, but for the engineers at the Bureau of Reclamation, it’s a waking nightmare. Basically, if the water drops too low, it can’t spin the turbines. No spinning turbines means no electricity for millions of people. But there is a weirder, scarier problem: the river outlets.

💡 You might also like: Convert US Dollars to Czech Crowns: What Most People Get Wrong

These are the "bypass" tubes used to send water downstream when the turbines aren't running. They were never designed to be the primary way the river flows. If we have to rely on them constantly because the reservoir is too low for the power intakes, the vibration and pressure might actually tear the pipes apart from the inside. It's like trying to run a fire hose through a straw made of glass.

Back in 1983, we almost lost the dam. Not because of a drought, but because of too much water. The spillways started cavitating—which is a fancy way of saying the water was moving so fast it created vacuum bubbles that literally ate the concrete. Huge chunks of the mountain were being spat out into the river. We learned then that the Glen Canyon Dam is a lot more fragile than it looks.

Is Lake Powell Just a Massive Evaporation Dish?

Environmentalists have been screaming about this for years. Groups like the Glen Canyon Institute argue that we should "Fill Mead First." The idea is simple: Lake Mead (behind Hoover Dam) and Lake Powell are both half-empty. Why keep two half-empty buckets in the desert sun where they both lose billions of gallons to evaporation?

Instead, why not drain Lake Powell into Lake Mead?

It sounds radical. To some, it sounds like heresy. But the numbers are hard to ignore. Lake Powell loses roughly 160 billion gallons of water to evaporation every single year. That’s enough to supply a city the size of Los Angeles for a long time. Plus, there's the "bank storage" issue. The sandstone walls of Glen Canyon are porous. They soak up water like a sponge. Estimates suggest that millions of acre-feet of water are just sitting in the rocks, unreachable and unusable.

The Ghost of the Canyon

As the water drops, something incredible—and kinda eerie—is happening. The old Glen Canyon is coming back to life. For fifty years, beautiful side canyons like Cathedral in the Desert were submerged under hundreds of feet of water. Now, hikers are walking into places that haven't been seen since the early 1960s.

You see the "bathtub ring"—that white mineral stain on the red rocks—towering 150 feet above your head. It’s a visual reminder of what we've lost and what we might be regaining. The sediment is a problem, though. Millions of tons of mud are trapped behind the dam. If the dam were ever decommissioned, dealing with that sludge would be one of the biggest engineering challenges in human history.

The Power Struggle: More Than Just Volts

The Glen Canyon Dam generates about 4 billion kilowatt-hours of energy annually. It feeds the Western Area Power Administration (WAPA) grid. Small rural cooperatives and tribal nations rely on this cheap hydropower. If the water hits "minimum power pool"—around 3,490 feet above sea level—the lights don't go out instantly, but the price of power skyrockets.

These communities would have to buy power on the open market, likely from natural gas plants. It’s an expensive, dirty alternative.

✨ Don't miss: Why Peace River Wildlife Center is Actually the Soul of Punta Gorda

- The Bureau of Reclamation has been experimenting with "Small-Unit" releases.

- They are looking at physical modifications to the dam to allow water to pass at lower levels.

- Policy makers are debating the 2026 Operating Guidelines, which will decide the fate of the river for the next decade.

It's a high-stakes game of chicken with Mother Nature.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Dam

You often hear that the dam is there to provide water to Phoenix. That’s not quite right. The Glen Canyon Dam was built primarily as a "savings account" for the Upper Basin states (Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, New Mexico). Its job is to ensure that these states can meet their legal obligation to send a specific amount of water to the Lower Basin (California, Arizona, Nevada) even in dry years.

Without the dam, the Upper Basin might be forced to shut off its own taps during a drought to satisfy California’s senior water rights. That’s why the politics are so messy. It’s not just about water; it’s about legal survival.

The Bureau of Reclamation recently released studies showing that if we don't change how we consume water, Lake Powell could hit dead pool within the next several years. That is a hard reality. We are currently using more water than the river provides. Period.

Actionable Insights for Navigating the Future of the Colorado River

If you live in the West or are planning to visit the region, the status of the Glen Canyon Dam affects everything from your utility bill to your vacation plans.

- Check Reservoir Levels Regularly: Use the USBR "Lower Colorado Region" water reports. Don't rely on old travel blogs. If you're heading to Lake Powell, many boat ramps are now permanently closed because they don't reach the water.

- Support Water Recycling over Desalination: Desalination is expensive and energy-intensive. Indirect potable reuse (recycling wastewater) is actually a more efficient way to reduce the strain on the Colorado River.

- Understand Your "Water Footprint": It's not just about the length of your shower. It's about the alfalfa grown in the desert and the beef raised on that alfalfa. Agriculture uses 80% of the river's water.

- Advocate for Infrastructure Retrofitting: The "bypass" tubes at Glen Canyon need urgent upgrades. Support federal funding for Bureau of Reclamation projects that focus on low-level water releases to prevent a total shutdown of the river.

The era of big dams is probably over. We won't build another one like the Glen Canyon Dam. Now, the challenge is learning how to live with the one we have—or figuring out how to let it go.

📖 Related: Embassy Suites Oklahoma City Medical Center: Why It Is Actually Different From Other OKC Hotels

Next Steps for Residents and Travelers:

If you are visiting the area, prioritize "Dry Camping" and respect the changing landscape of the river. For residents, check your local municipal water board's 10-year drought plan. If they don't have a plan for Lake Powell hitting dead pool, it’s time to start asking questions at the next city council meeting.