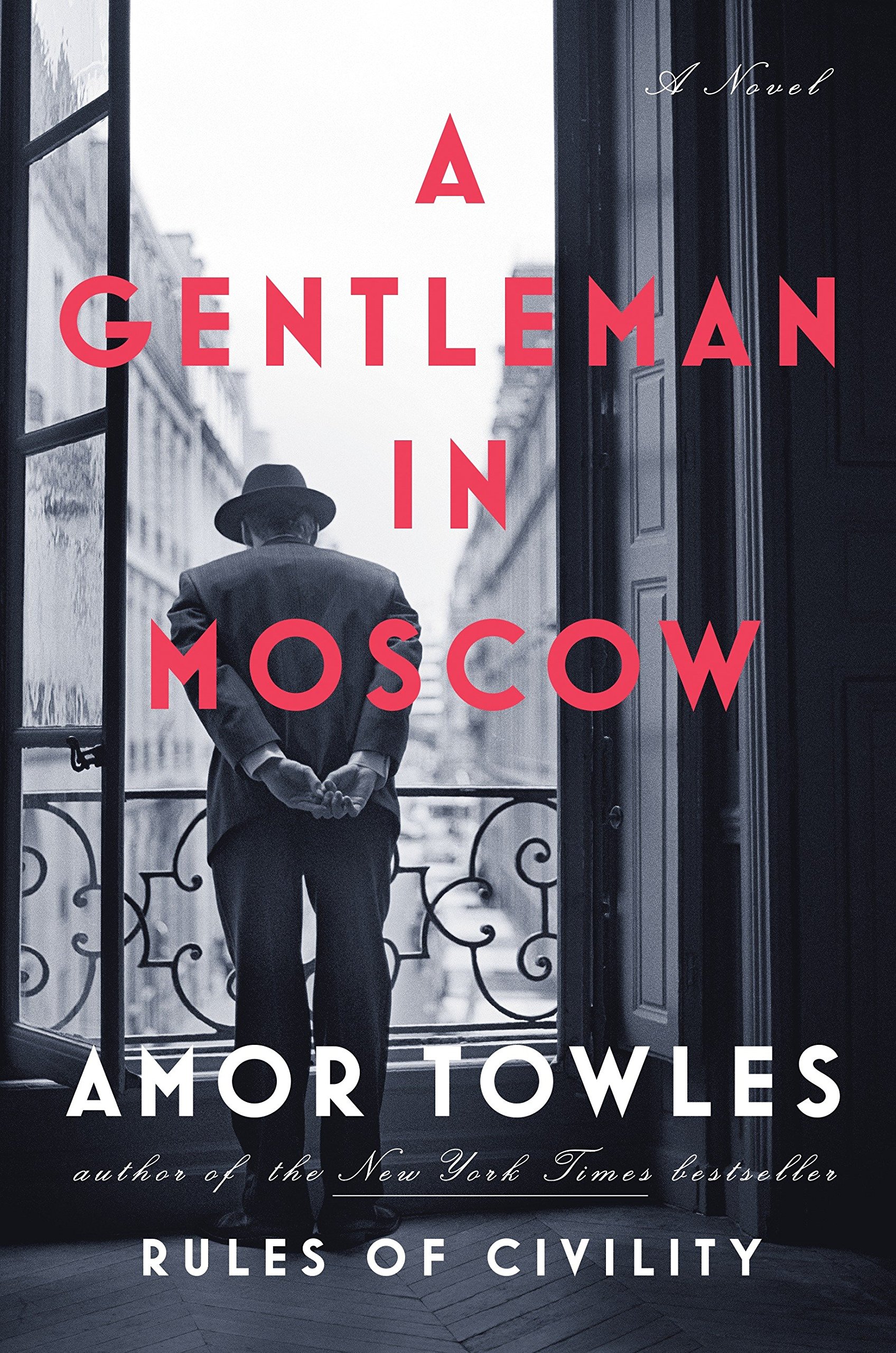

Honestly, the first time you pick up The Gentleman in Moscow book, it feels like a trick. Amor Towles basically asks you to spend nearly 500 pages inside a single building. It sounds claustrophobic. It sounds like a recipe for a very long nap. But then you meet Count Alexander Ilyich Rostov, and suddenly, the Metropol Hotel feels larger than the entire Soviet Union combined.

The premise is deceptively simple. In 1922, a Bolshevik tribunal spares the Count from a firing squad because of a poem he supposedly wrote years earlier. Instead of death, they sentence him to house arrest. The catch? He has to live in a cramped attic room of the luxurious Metropol, the very hotel where he used to occupy a suite. If he ever steps foot outside, he’s a dead man.

It’s a story about a man losing everything—his status, his wealth, his family estate—and yet somehow becoming more "rich" than he ever was as an aristocrat. Towles creates this incredible friction between the crumbling, chaotic world of the early USSR and the refined, static world inside the hotel walls.

🔗 Read more: Thomas Had Never Seen Such a Mess: Why This Sassy Meme Still Rules the Internet

The Reality of the Metropol Hotel

A lot of people think the Metropol is a fictional creation. It isn’t. If you fly to Moscow today, you can literally book a room there. It stands right across from the Bolshoi Theatre. During the Russian Revolution, it really was a hub for high society, diplomats, and eventually, the new Soviet elite.

Towles isn't just making up the atmosphere. He draws on the actual history of the "Former People"—the lishentsy. These were the aristocrats, priests, and former imperial officials who were stripped of their rights after 1917. Most met a much darker fate than Rostov. They were sent to gulags or executed in the Lubyanka. By giving Rostov a "gilded cage," Towles explores a very specific, weird slice of history where the old world and the new world were forced to share the same dinner menu.

It's about survival. Not the "finding water in the desert" kind of survival, but the "how do I keep my soul intact when my world is gone" kind.

Why the "Attic" Matters More Than the Suite

When Rostov is moved from his grand suite to the servant's quarters in the attic, he brings a few prized possessions: a portrait, some books, and a desk. That’s it.

The book leans heavily into the idea that "if a man does not master his circumstances then he is bound to be mastered by them." It’s a bit of a mantra for the Count. He decides that even if he’s stuck in a room with a sloped ceiling, he will still be the most punctual, well-mannered, and observant man in Russia.

He becomes a waiter. Think about that for a second. A man who used to own estates is now serving wine to the people who took those estates away. But he doesn't do it with bitterness. He does it with a level of expertise that makes the Bolsheviks look like amateurs.

The Politics of a Bottle of Wine

There’s this famous scene in The Gentleman in Moscow book involving a wine cellar. The Soviet government, in a fit of radical egalitarianism, orders that all labels be removed from the hotel's thousands of wine bottles. The idea was that in a perfect communist society, there should be no "superior" vintage. A bottle of wine is just a bottle of wine.

It’s a hilarious and heartbreaking detail. It perfectly illustrates the absurdity of the era. To the Count, this is a tragedy because wine represents history, geography, and craft. To the "Bishop"—the book's sniveling antagonist who climbs the party ranks—it's just a way to show loyalty to the new regime.

This conflict drives the middle of the book. It’s not about grand battles. It’s about the battle to maintain standards in a world that is actively trying to flatten them.

Sofia and the Shift in Stakes

The book changes halfway through. For the first couple of hundred pages, it’s mostly about the Count’s routines, his friendship with a little girl named Nina, and his clandestine dinners. Then, Nina grows up and leaves, eventually dropping off her own daughter, Sofia, at the hotel.

Suddenly, the Count isn't just surviving for himself. He’s a father.

This is where Towles really shows his hand. The book stops being a clever character study and turns into a high-stakes thriller, albeit a very slow-burning one. The Count has to figure out how to give Sofia a future in a country that is becoming increasingly dangerous under Stalin’s shadow.

The Metropol becomes a microcosm of the world. You see the Purges happening through the disappearance of hotel staff. You see the Cold War starting through the hushed conversations of foreign journalists at the bar. It’s brilliant because you never leave the hotel, yet you feel the weight of the 20th century pressing against the windows.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Count

There is a common criticism that the Count is "too perfect." That he’s a Mary Sue in a three-piece suit.

But if you look closer, he’s deeply flawed. He’s a man who was ready to end his own life before a chance encounter changed his mind. He is incredibly lucky. He’s also a bit of a dinosaur. His obsession with etiquette is a defense mechanism against the fact that he is essentially a prisoner.

The beauty of The Gentleman in Moscow book isn't that Rostov is a hero; it's that he chooses to be kind when it would be much easier to be cynical. In a time of secret police and informants, he builds a family out of a chef and a headwaiter (the "Triumvirate").

The Ending That Everyone Talks About

I won't spoil the specifics if you haven't finished it, but the payoff is one of the most satisfying in modern fiction. It’s a "long game" ending. Elements mentioned in the first fifty pages—clocks, hidden compartments, old friendships—all snap together like a well-oiled machine.

It’s a reminder that even when you are confined, your influence can reach far beyond your walls.

Actionable Insights for Readers and Writers

If you’re reading this book for the first time, or if you’re looking to apply its "vibe" to your own life or work, here’s how to actually digest it:

- Focus on the "Small Rituals": The Count survives by making his morning coffee a ceremony. In your own life, find one mundane task and do it with extreme intention. It’s a grounding technique that works.

- Study the "Rule of Three": Towles uses the Triumvirate (the Chef, the Maître d', and the Count) to show how different skill sets create a whole. Whether in business or a social circle, you need the creator, the organizer, and the diplomat.

- Look for the Gilded Cage: We all have constraints—jobs, locations, health. The book asks: how do you expand the space you do have? Rostov used the hotel's hidden passages and rooftops. Look for the "hidden passages" in your own constraints.

- The Power of Memory: The Count lives in the past but doesn't let it rot him. He uses his knowledge of the old world to navigate the new one. Use your history as a tool, not a weight.

The book isn't just a historical novel. It’s a manual on how to keep your dignity when the world decides it doesn't want you to have any. It’s why people keep coming back to it. It’s why it was turned into a high-budget series.

Ultimately, it’s a story about a man who was sentenced to a small life and decided to make it massive.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Experience:

- Check the Real Metropol: Look up the floor plans and photos of the Metropol Hotel in Moscow circa 1920. Seeing the Shaliapin Bar and the fountain in the Piazza restaurant makes the scenes in the book feel 10x more visceral.

- Read the "Interludes": Pay close attention to the "Addendums" and "Chronicles" sections in the text. Towles uses these to provide historical context that the Count, in his isolation, might not explicitly mention.

- Explore the Soundtrack: The book is obsessed with music, from Mozart to Tchaikovsky. Play the pieces mentioned in the chapters as you read them; the atmosphere shift is incredible.