Westeros. It’s huge. Honestly, the first time you saw that sprawling continent in the opening credits, it felt like a puzzle. You’ve got the Wall in the north, King’s Landing in the middle, and a whole lot of "wait, how far away is that?" in between. Back in 2011, when George R.R. Martin’s world first hit HBO, the Game of Thrones Season 1 map wasn't just a piece of set dressing. It was a lifeline. Without it, you’d be totally lost.

Geography is destiny in this show.

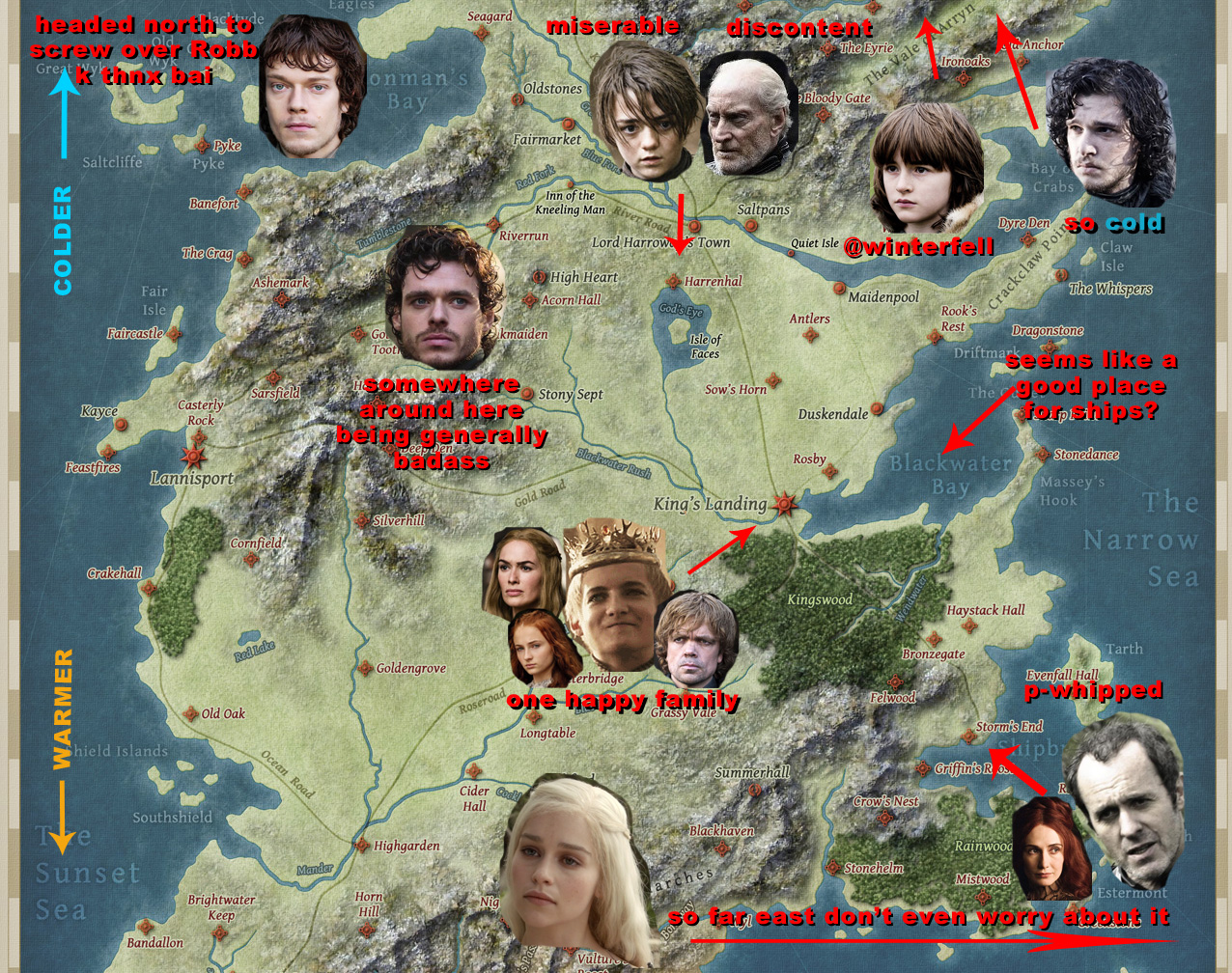

If you don’t understand where Winterfell is in relation to the Eyrie, the political stakes of the first ten episodes basically evaporate. It’s not just about pretty lines on parchment. It’s about logistics. It’s about why Ned Stark’s journey south felt like a slow-motion car crash and why Catelyn Stark bumping into Tyrion Lannister at the Crossroads Inn was a statistically improbable disaster.

The Layout of the Seven Kingdoms

Westeros is skinny. Think of it as a tall, jagged rectangle roughly the size of South America, though Martin has compared it to an upside-down Ireland. In Season 1, the world feels incredibly grounded because the characters are actually traveling. There’s no "fast travel" yet. No one is teleporting across the Narrow Sea.

Up North, everything is gray and white. The North is larger than the other six kingdoms combined. It’s a massive, empty space. When King Robert Baratheon brings his massive wheelhouse up to Winterfell, the map tells us it took them a month. One month of bumping along the Kingsroad. That distance matters. It establishes the isolation of the Starks. They aren't just culturally different from the Southerners; they are physically removed from the "civilization" of the capital.

Then you have the Riverlands. This is the geographic heart of the continent. It’s the "Crosroads" for a reason. Because the Trident river system flows through here, everyone has to pass through. That’s why the map in Season 1 focuses so heavily on places like the Inn at the Crossroads. It’s the only place where stories can collide. If you look at a map of the Riverlands, you see why it’s always a war zone. It has no natural borders. No mountains to hide behind. It’s just open fields and water, making it the perfect place for the Lannisters and Starks to eventually start tearing each other apart.

Why the Opening Credits Map Was Revolutionary

We have to talk about the clockwork.

✨ Don't miss: Why La Mera Mera Radio is Actually Dominating Local Airwaves Right Now

Angus Wall and the team at Elastic created the title sequence that became iconic. But did you notice how the Game of Thrones Season 1 map changed every week? It wasn't static. If the episode didn't go to The Wall, the camera didn't pan there. This was a brilliant move by showrunners David Benioff and D.B. Weiss to keep the audience oriented.

The map was built on the inside of a sphere. Why? Because the sun is in the middle. It’s a Dyson sphere-inspired design that suggests the world is contained, yet vast. In Season 1, the map focus was tight. We saw Winterfell, The Wall, King’s Landing, and across the water to Vaes Dothrak. That’s it. The world felt smaller then, focused on the immediate fallout of Jon Arryn’s death.

Every time a gear turned and a castle rose out of the ground, it gave the viewer a sense of "You Are Here." It’s a psychological trick. By showing the location in the credits, the writers didn't have to waste dialogue explaining that a character had moved 500 miles. You already saw the token move on the board.

The Essos Problem

Across the Narrow Sea, things get a bit weirder. While Westeros is structured like medieval Europe, the Essos portion of the Game of Thrones Season 1 map is a vast, dusty expanse. In the first season, we really only see the Free City of Pentos and then the Dothraki Sea.

Pentos is right across the water from King’s Landing. It’s close enough to be a threat, but far enough that the Baratheons can ignore it. But look at the distance to Vaes Dothrak. It’s thousands of miles. When Daenerys Targaryen begins her trek with the khalasar, the map is our only way of understanding her isolation. She isn't just in another country; she’s at the end of the world. There are no roads there. No inns. Just the "Great Grass Sea."

The contrast between the structured, road-heavy map of Westeros and the wide-open, borderless Essos map highlights the cultural divide. The Dothraki don't care about lines on a page. They care about where the grass is.

🔗 Read more: Why Love Island Season 7 Episode 23 Still Feels Like a Fever Dream

Strategic Chokepoints You Might Have Missed

If you’re looking at a detailed map of the first season, three spots stand out as absolutely vital for the plot.

- The Neck: This is the swampy bit that connects the North to the South. It’s held by the Reeds (though we don't meet them until later). In Season 1, this is the bottleneck. If you want to get an army south, you go through here. If you want to stop an army coming north, you stop them at Moat Cailin.

- The Vale: To the east, you have the Eyrie. Look at the mountains on the map. They are impassable. The only way in is through the Bloody Gate. This explains why Lysa Arryn felt so safe being a hermit while the rest of the world burned. She had the best defensive position on the entire map.

- The Trident: Specifically the Green Fork. This is where the big battles happen. It’s where Robert killed Rhaegar years before the show started, and it’s where the political tensions of Season 1 finally snap.

Misconceptions About Distances

People always complain about "jetpack" travel in later seasons. But in Season 1, the map was a cruel mistress.

The Kingsroad is roughly 1,500 miles from King's Landing to the Wall. A horse can do maybe 30 miles a day if you're pushing it. Do the math. That’s a 50-day trip. When Ned Stark leaves Winterfell in episode two and arrives in King’s Landing in episode three, weeks have passed. The map forces the story to slow down. It gives the characters time to talk, to argue, and to grow.

Some fans think Dragonstone is far away. It’s not. It’s right off the coast of King’s Landing. In Season 1, we hear about Stannis Baratheon brooding there. If you look at the map, you realize he’s basically sitting in the capital's front yard, staring at them. That proximity adds a layer of tension that isn't explicitly spelled out in the dialogue, but it’s right there in the geography.

Using the Map to Predict the War

By the end of the first season, the map has changed. The "War of the Five Kings" hasn't fully exploded yet, but the pieces are set. Robb Stark is at Riverrun. Tywin Lannister is in the field.

If you trace the movements on a Game of Thrones Season 1 map, you see the pincer movement the Lannisters were attempting. They were squeezing the Riverlands from the West (Casterly Rock) and the South (King's Landing). Robb Stark’s brilliance was in his movement—splitting his army at the Twins. The Twins, owned by Walder Frey, is the only bridge over the Green Fork for hundreds of miles.

💡 You might also like: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

Without that bridge, Robb is stuck. With it, he surprises Jaime Lannister at the Whispering Wood. The map is the plot here. If Walder Frey says no, the Starks lose the war in episode nine.

Actionable Insights for Your Next Rewatch

To truly appreciate the world-building, don't just watch the scenes. Watch the geography.

- Track the Direwolves: Notice how the direwolves are increasingly uncomfortable the further south they get. The map shows you why; they are moving away from the "Magic" of the North and into the "Politics" of the South.

- Watch the Water: Most of the power players in Season 1 are defined by their proximity to water. The Lannisters have Lannisport, the Starks have the White Knife, and the Targaryens are defined by the Narrow Sea they can't yet cross.

- Check the Terrain: Note how the armor changes. In the North, it’s furs and heavy leather. In the South, it’s light steel and silks. The map dictates the fashion.

- Follow the Smallfolk: Listen to the names of the tiny villages characters pass through. They aren't random. They are usually situated at river bends or mountain passes visible on the official tactical maps.

The map of Westeros is a character in its own right. It’s a harsh, unforgiving land that punishes those who don't respect its scale. In Season 1, that scale was everything. It made the world feel "real" in a way that very few fantasy shows have managed since.

To get the most out of a rewatch, keep a high-resolution version of the Westeros map open on your phone. When Tyrion talks about the "Stoneway" or the "Boneway," find it. When Catelyn travels from Winterfell to King's Landing by ship, track the coastline. You'll realize that the betrayals and alliances aren't just based on who likes whom—they're based on who controls which road.

Next time you see those gears turning in the intro, remember that every mountain range and river is a barrier that shaped the fate of the Seven Kingdoms.

Key Takeaways for Fans:

- The Kingsroad is the literal spine of the first season's narrative.

- Geography explains the cultural isolation of the North and the vulnerability of the Riverlands.

- The "clockwork" map in the credits was designed to orient viewers to the week's specific locations.

- Distance in Season 1 is a plot device used to build tension and allow for character development during travel.