The Fung Wah bus was a vibe before "vibes" were even a thing. Honestly, if you lived in Boston or New York City between 1996 and 2013, you probably have a story about it. Maybe your story involves a breakdown on the side of I-95. Perhaps it involves a driver who treated the Mass Pike like a qualifying lap for the Daytona 500. Or maybe you just remember the absolute, incomparable joy of handing over a crisp $10 bill and getting a seat on a bus that would actually get you to South Station in under four hours. It was chaos. It was legendary. And then, it was gone.

The Wild West of the Fung Wah Chinatown Bus

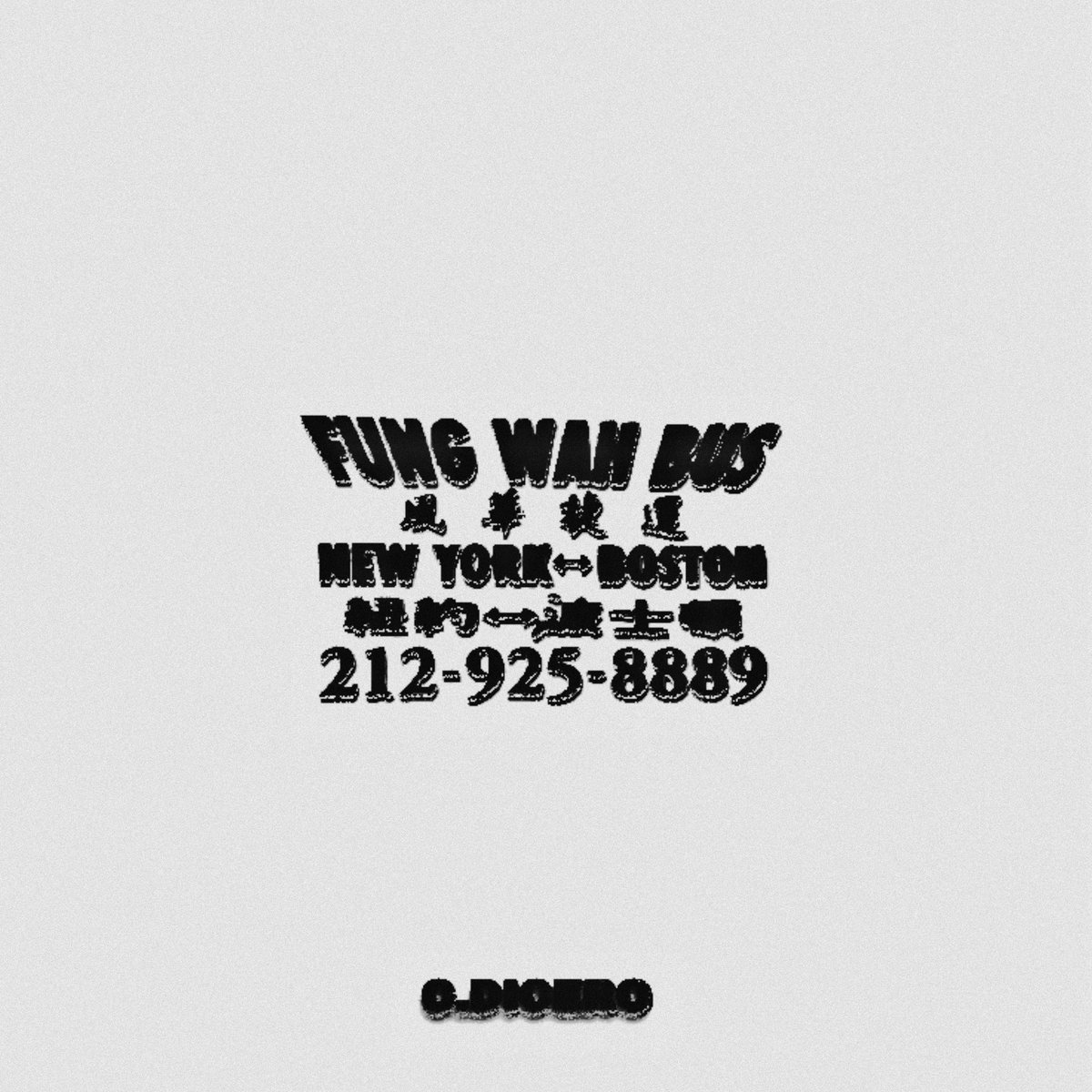

Pei Lin Liang started Fung Wah Transportation in 1996. Initially, it wasn't even for the public; it was basically a van service for Chinese immigrant workers moving between the New York and Boston Chinatowns. But college students are smart. They figured out that instead of paying $50 or $60 for a Greyhound or a Peter Pan bus—or the even more expensive Amtrak—they could just wander down to Canal Street and hop on a white van for a fraction of the price.

It was the original disruptor. Long before Uber or Airbnb tried to "move fast and break things," the Fung Wah Chinatown bus was already breaking things. Usually literal things. Like transmissions.

By the early 2000s, the "Chinatown bus" had become a cultural phenomenon. The business model was deceptively simple: low overhead, high frequency, and zero frills. You didn't get a ticket. You got a handwritten slip of paper or just a nod. There were no terminals. You waited on a sidewalk, often in the rain, dodging guys selling knockoff handbags until the bus pulled up.

Safety Records and the Federal Crackdown

The legend of the Fung Wah wasn't just about the price. It was about the danger. Or the perceived danger. While the buses were notorious for mechanical failures, the actual safety data from the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) eventually painted a grim picture that couldn't be ignored by regulators.

💡 You might also like: Why the Newport Back Bay Science Center is the Best Kept Secret in Orange County

In 2005, a Fung Wah bus actually caught fire on the Massachusetts Turnpike. All 45 passengers made it off before the thing turned into a fireball. Then there were the rollovers. In 2006, a bus flipped in Auburn, Massachusetts. The headlines were relentless. People started calling them "chicken buses."

But travelers kept coming. Why? Because the alternatives sucked.

If you were a broke student at BU or NYU, you took the risk. You’d sit there, smelling the faint aroma of exhaust fumes and someone's leftover pork buns, praying the driver didn't have a lead foot. Most of the time, you arrived early. That was the crazy part. These drivers were fast. They knew every shortcut, every way to bypass the George Washington Bridge traffic, and they drove like their lives depended on the turnaround time.

The Final Stop

The end didn't come because people stopped riding. It came because the government finally had enough. In February 2013, the FMCSA issued an "imminent hazard" out-of-service order. Inspectors had found massive cracks in the frames of several buses. They weren't just old; they were structurally unsound.

📖 Related: Flights from San Diego to New Jersey: What Most People Get Wrong

Regulators discovered that Fung Wah had been skipping safety inspections and falsifying records. It wasn't just a quirky, budget-friendly way to travel anymore. It was a liability. By 2015, Pei Lin Liang officially gave up on trying to relaunch the brand. The red and white logo vanished from the streets of Manhattan.

Why the "Fung Wah" Model Changed Travel Forever

Even though the Fung Wah Chinatown bus is dead, its DNA is everywhere. Look at Megabus. Look at BoltBus (which also eventually folded). These companies saw that Fung Wah had tapped into a massive, underserved market: people who don't care about a terminal if the price is right.

Before Fung Wah, the bus industry was a slow-moving monopoly. After Fung Wah, everyone had to compete on price. They proved that if you make travel cheap enough, people will put up with almost anything.

We see this today in the "ultra-low-cost carrier" model used by airlines like Spirit or Frontier. It's the same philosophy. Strip away the luggage, the snacks, the legroom, and the dignity. If the fare is $19, the plane will be full.

👉 See also: Woman on a Plane: What the Viral Trends and Real Travel Stats Actually Tell Us

The Cultural Legacy of Canal Street

There is a specific kind of nostalgia for that era of New York. Before the West Village was entirely luxury condos and before South Station in Boston was completely sanitized. The Fung Wah represented a grittier, more accessible version of the Northeast corridor.

It wasn't just about the bus; it was about the ecosystem. You’d grab a $3 bahn mi across the street, wait in a chaotic line that was more of a "suggestion" than a queue, and listen to the engine idle. It felt like an adventure. Today, everything is app-based and sanitized. You track your bus on a map. You have a QR code. It's better, safer, and objectively "correct." But it's also a little boring.

Common Misconceptions About the Chinatown Lines

- They were all owned by the same people: No. Fung Wah was the king, but Travel-2000, Lucky Star, and others were fierce competitors. They would sometimes have "price wars" right there on the sidewalk, dropping the NYC-Boston fare to $5 just to spite each other.

- They were never inspected: They were, but the companies were notorious for "rebranding" under a new DOT number once they accumulated too many violations. It was a game of regulatory whack-a-mole.

- The drivers didn't speak English: Most spoke enough to get the job done, but the language barrier often worked in their favor when dealing with annoyed passengers or confused traffic cops.

What to Look for in Budget Bus Travel Today

If you're trying to recreate the Fung Wah experience (safely) in 2026, the landscape has shifted toward consolidation. FlixBus and Greyhound (now owned by the same parent company) dominate the market. However, a few independent Chinatown lines still run out of the Lower East Side and Flushing.

- Check the Safety Rating: You can actually look up any bus company's safety record on the FMCSA’s SAFER website. If they have a high "Unsafe Driving" percentile, maybe reconsider that $15 ticket.

- Verify the Pickup Point: Many of the remaining "curbside" carriers have been forced into designated bus slips to reduce city congestion. Don't just show up to the old corner of Canal and Chrysler.

- Expect Nothing: The golden rule of the Fung Wah Chinatown bus remains: you are paying for transport, not hospitality. Bring your own water, a fully charged power bank, and a heavy dose of patience.

The era of the $10 white-knuckle ride to Boston is over, but the impact it had on how we move between cities is permanent. We traded the chaos for safety, which is a good trade. Usually. But for those who lived through the Fung Wah years, every quiet, scheduled, "safe" bus ride feels just a little bit less like a story worth telling.

To find the current spiritual successors, you have to look toward the smaller operators still running out of 7th Avenue or the outskirts of Chinatown. They aren't as famous, and they are definitely more regulated, but the spirit of the budget-friendly, no-nonsense trek remains alive for anyone willing to skip the Amtrak Acela and brave the highway.

Actionable Next Steps for Travelers:

- Research Current Carriers: If you’re looking for the modern equivalent, check out Lucky Star or Go Buses. They operate with much higher safety standards but maintain the competitive pricing Fung Wah pioneered.

- Use Aggregators: Use sites like Wanderu or Busbud to compare the independent Chinatown lines against the corporate giants. Often, the independent lines still offer better direct routes between ethnic enclaves that Greyhound bypasses.

- Monitor Safety Data: Before booking an unfamiliar line, enter the company name into the FMCSA SMS (Safety Measurement System) search tool. It takes 30 seconds and tells you if they’ve had recent vehicle maintenance issues or driver fatigue violations.